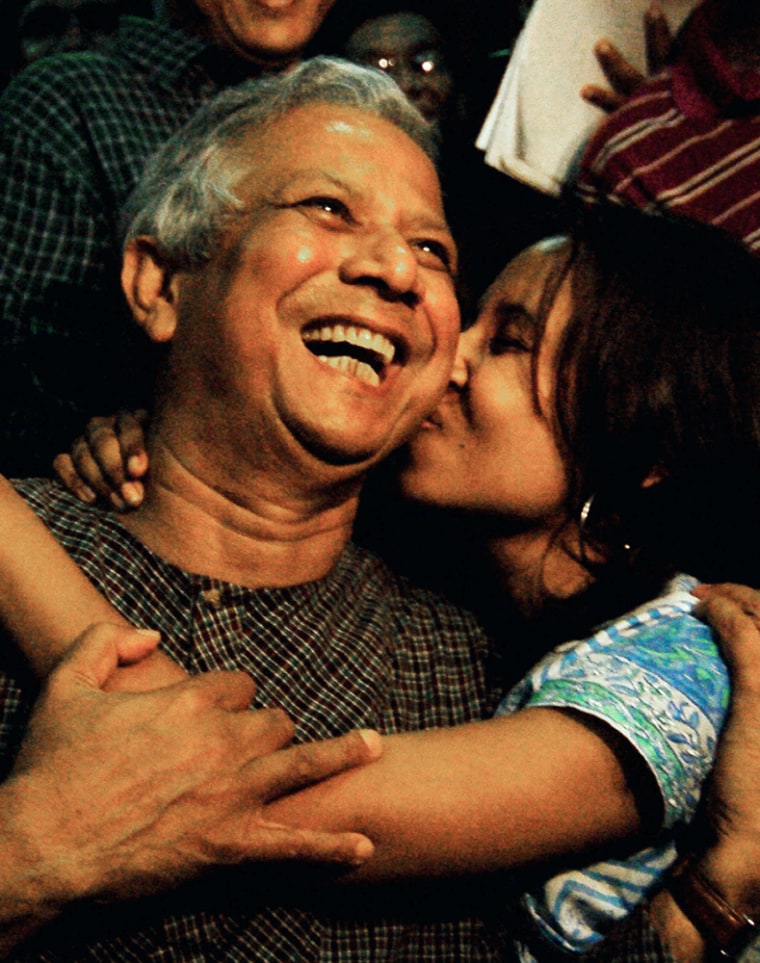

Bangladeshi economist Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen Bank he founded won the Nobel Peace Prize on Friday for their pioneering use of tiny, seemingly insignificant loans — microcredit — to lift millions out of poverty.

Through Yunus’s efforts and those of the bank he founded, poor people around the world, especially women, have been able to buy cows, a few chickens or the cell phone they desperately needed to get ahead.

The 65-year-old economist said he would use part of his share of the $1.4 million award money to create a company to make low-cost, high-nutrition food for the poor. The rest would go toward setting up an eye hospital for the poor in Bangladesh, he said.

The food company, to be known as Social Business Enterprise, will sell food for a nominal price, he said.

“Lasting peace cannot be achieved unless large population groups find ways in which to break out of poverty,” the Nobel Committee said in its citation. “Microcredit is one such means. Development from below also serves to advance democracy and human rights.”

Yunus is the first Nobel Prize winner from Bangladesh, a poverty-stricken nation of about 141 million people located on the Bay on Bengal.

“I am so, so happy, it’s really a great news for the whole nation,” Yunus told The Associated Press shortly after the prize was announced. He was reached by telephone at his home in the Bangladeshi capital Dhaka.

Grameen Bank was the first lender to hand out microcredit, giving very small loans to poor Bangladeshis who did not qualify for loans from conventional banks. No collateral is needed and repayment is based on an honor system.

Anyone can qualify for a loan — the average is about $200 — but recipients are put in groups of five. Once two members of the group have borrowed money, the other three must wait for the funds to be repaid before they get a loan.

Grameen, which means rural in the Bengali language, says the method encourages social responsibility. The results are hard to argue with — the bank says it has a 99 percent repayment rate.

Since Yunus gave out his first loans in 1974, microcredit schemes have spread throughout the developing world and are now considered a key to alleviating poverty and spurring development.

Yunus told The Associated Press in a 2004 interview that his “eureka moment” came while chatting to a shy woman weaving bamboo stools with calloused fingers.

Sufia Begum was a 21-year-old villager and a mother of three when the economics professor met her in 1974 and asked her how much she earned. She replied that she borrowed about five taka (nine cents) from a middleman for the bamboo for each stool.

All but two cents of that went back to the lender.

“I thought to myself, my God, for five takas she has become a slave,” Yunus said in the interview.

“I couldn’t understand how she could be so poor when she was making such beautiful things,” he said.

The following day, he and his students did a survey in the woman’s village, Jobra, and discovered that 43 of the villagers owed a total of 856 taka (about $27).

“I couldn’t take it anymore. I put the $27 out there and told them they could liberate themselves,” he said, and pay him back whenever they could. The idea was to buy their own materials and cut out the middleman.

They all paid him back, day by day, over a year, and his spur-of-the-moment generosity grew into a full-fledged business concept that came to fruition with the founding of Grameen Bank in 1983.

In the years since, the bank says it has lent $5.72 billion to more than 6 million Bangladeshis.

Worldwide, microcredit financing is estimated to have helped 92 million families last year alone, according to Jove Oliver, spokesman for the Microcredit Summit Campaign, part of the Washington-based Project Results Educational Fund.

“Yunus and Grameen Bank have shown that even the poorest of the poor can work to bring about their own development,” the Nobel citation said.

Today, the bank claims to have 6.6 million borrowers, 97 percent of whom are women, and provides services in more than 70,000 villages in Bangladesh. Its model of micro-financing has inspired similar efforts around the world.

The success has allowed Grameen Bank to expand its credit to include housing loans, financing for irrigation and fisheries as well as traditional savings accounts.

One of Yunus’ aides, Dipal Barua, said the award was an “honor for millions of poor women who have made this possible.”

Ole Danbolt Mjoes, chairman of the Nobel committee that awarded the prize, told The AP that Yunus’s efforts have had visible results: “We are saying microcredit is an important contribution that cannot fix everything, but is a big help.”

Mjoes said at least three previous prizes have recognized the need to alleviate poverty and hunger.

Those were the 1970 prize to American agriculturalist Norman Borlaug for his program in Mexico to feed the hungry by improving wheat yields; the 1969 award to the Geneva-based International Labor Organization for its efforts to ease poverty; and the 1949 award to Baron John Boyd Orr, as head of the U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization who worked to persuade nations to make it a public policy to feed the poor.

The peace prize was the sixth and last Nobel prize announced this year. The others, for physics, chemistry, medicine, literature and economics, were announced in Stockholm, Sweden.