When same-sex marriage became legal in Massachusetts, among those who tied the knot were former Rep. Gerry Studds and Dean Hara.

But getting married didn’t protect them under federal law: Hara has learned he is not eligible for any portion of Studds’ estimated annual $114,337 pension following his partner’s death last week.

The 1996 federal Defense of Marriage Act blocks the federal government from recognizing the 2004 marriage between Studds and Hara or other same-sex couples.

Studds voted against the act, which was passed July 12, 1996, by a vote of 342-67, according to the House Clerk’s office.

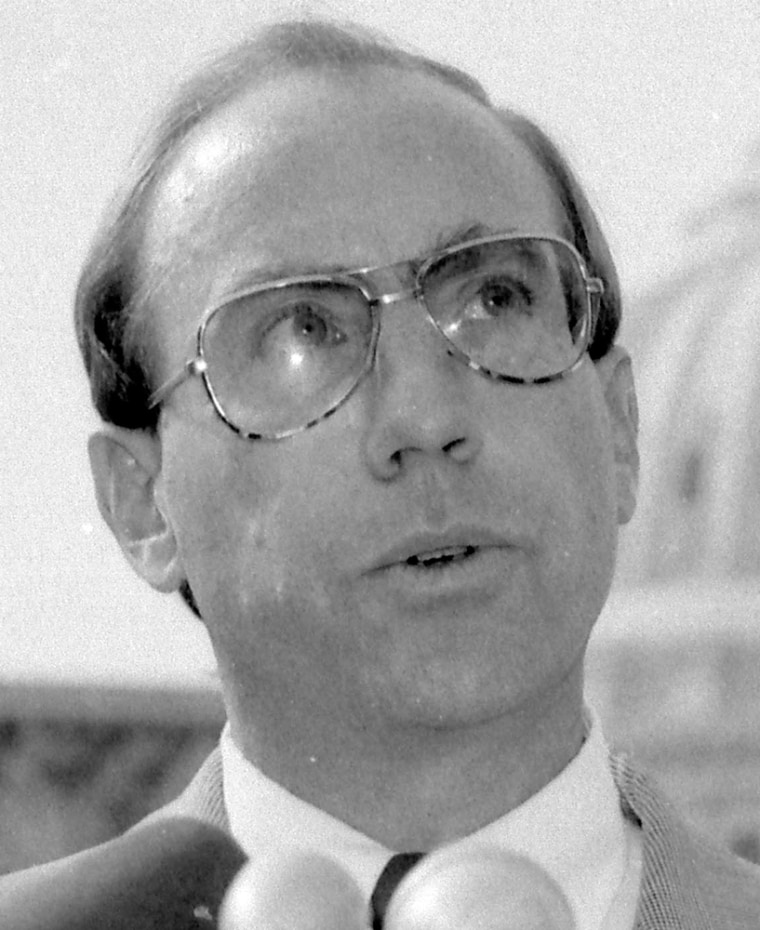

Studds, a Democrat, became the first openly gay member of U.S. House when his homosexuality was exposed during a 1983 teenage page sex scandal. He retired from political life in 1997 and died Saturday at age 69.

Gary Buseck, legal director for Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders, said the death of Studds may illuminate an inequity Congress enacted in “an era of fear and trepidation of gay marriage” when it appeared Hawaii might allow same-sex marriage.

“This is maybe a moment of education for Congress,” he said. “Now they have a death in the congressional family of one of their distinguished members whose spouse is being treated differently than any of their spouses.”

Hara, 48, declined comment.

Peter Graves, a spokesman for U.S. Office of Personnel Management, which administers the congressional pension program, said same-sex partners are not recognized as spouses for any marriage-related benefits.

First of its kind

He said Studds is the first case of its kind as far as the office could determine. “Our office could not think of a similar situation having occurred,” he said.

Graves said Studds had other options. He could have had an insurable interest annuity, similar to buying an insurance policy, which is allowed under both the civil service and the federal employee retirement system and does not come under the restrictions of the Defense of Marriage Act. Graves said he didn’t know if Studds used that option.

Pete Sepp, spokesman for National Taxpayers Union, a nonprofit citizen watchdog group, estimated Studds’ annual pension at $114,337, adjusted for inflation.

That would have made Hara eligible for a lifetime annual pension of about $62,000, which would grow with inflation, if the marriage was recognized by the federal government, Sepp said.

In 2003 the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that the state couldn’t deny marriage licenses to same-sex couples under the state constitution. The ruling paved the way for the first gay marriages in Massachusetts the following year.

Massachusetts is the only state to allow same-sex couples to marry, although there is a push to amend the state constitution to define marriage as the union of a man and woman.

Studds was first elected in 1972 in a conservative district, and quickly became known for his work to protect the marine environment and fishing industry.

In 1983, a 27-year-old man stepped forward to disclose that he and Studds had had a sexual relationship a decade earlier when he was a teenage congressional page. The House censured Studds, who revealed that he was gay. Voters re-elected him until he retired in 1997.