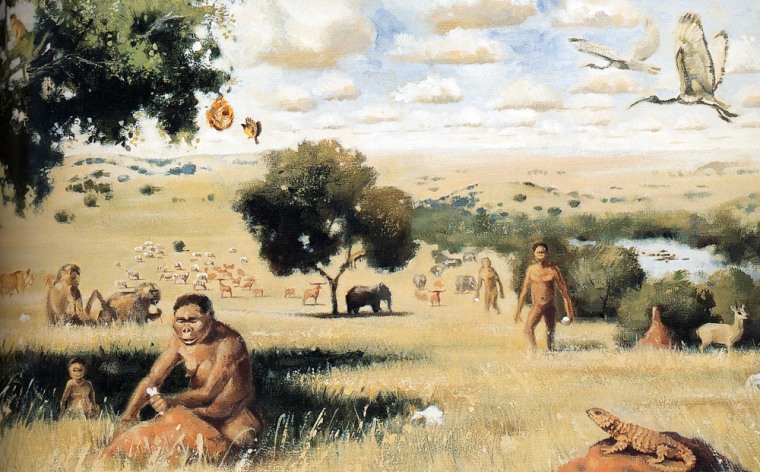

Early human ancestors chowed down on more than fruits and leaves, a new study finds. They also fed on grasses, roots, and grazing animals as early as a million years ago.

Using laser to remove small samples from the teeth of four ape-like species—known as Paranthropus robustus—whose remains were found in South Africa, researchers were able to determine what was on their menu.

"By analyzing tooth enamel, we found that they ate lots of different things, and what they ate changed during the year," said study co-author Ben Passey, a University of Utah geology doctoral student. “One possibility is that they were migrating seasonally between more forested habitats to more open, savanna habitats."

Plants fall into two categories based on how they use photosynthesis to convert sunlight, water and carbon dioxide into plant matter. A look at their carbon ratios make it possible to tell which category a plant belongs to.

Forested areas are rich in fruits and leaves—plants known as C3—while plants that grow in savanna habitats—C4—include potato-like tubers, grasses, and seeds.

The tooth enamel is basically a record keeper of how much C3 and C4 plants are consumed.

Until now, lasers were too damaging to use on small samples such as human teeth or even the larger teeth of their ancestors.

"What I did was fine-tune the method to handle very small samples like human-sized teeth," Passey said. "If you tried the previous method on a human tooth, you would blast a hole clear through the enamel, and museum curators wouldn't like that."

The finding, detailed in the Nov. 10 issue of the journal Science, casts doubts on the notion that Paranthropus became extinct about a million years ago because it didn’t have a varied diet when Africa dried up.

"We need to seriously rethink the reason behind the ultimate fate of Paranthropus," said study lead author Matt Sponheimer from the University of Colorado at Boulder. "This 'who done it' or 'what done it' mystery is not likely to be resolved any time soon."