Americans’ charitable spirit peaks during the holiday season, but this year the urge to give is battling a strong contrarian tide – a crisis of trust born from public disenchantment with a philanthropic system that many consider disorganized, under-regulated and tainted by scandal.

A poll by Harris Interactive released this summer found only one in 10 Americans strongly believes charities are "honest and ethical" in their use of donated funds. And nearly one in three believes nonprofits have "pretty seriously gotten off in the wrong direction," it found.

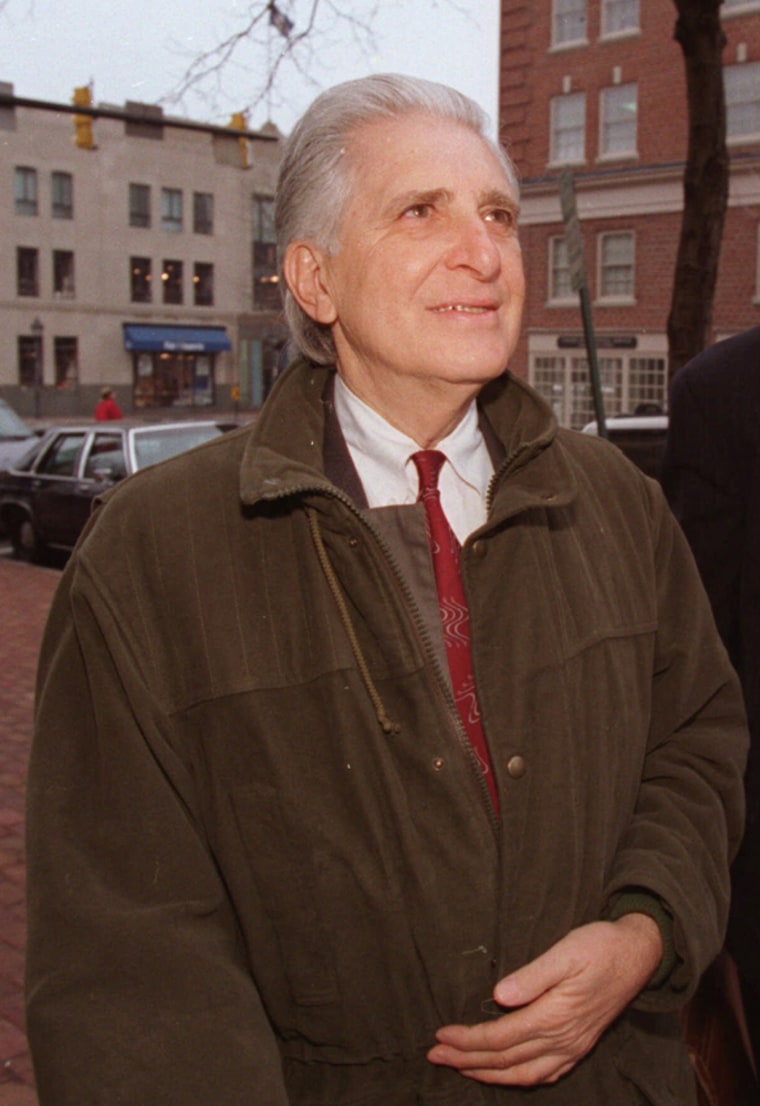

"The public believed we would make things better," said Robert Egger, founder of the D.C. Central Kitchen food recycling and distribution center, speaking of the broad charitable sector. "Now they’re saying, ‘I’ve been giving for 40 years. … We’ve invested huge amounts of coin and soul into this sector; what are (we) getting in return?’ What they get is more and more dire predictions, more people asking for help."

The doubts matter, because average Americans are just as critical to the health of U.S. philanthropy as Warren Buffett and Bill Gates.

Americans, both individuals and corporations, gave $260 billion to nonprofit organizations last year, according to the National Center for Charitable Statistics’ Nonprofit Almanac 2007, highlights of which were released last week.

Individuals and households accounted for $199 billion of the total — giving away nearly 2 percent of their incomes on average, it said.

Similarly, recent surveys by the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University found that people making less than $50,000 a year make most of the donations to U.S. charities and that the median gift after major disasters is $50 – the kind of donation that comes from cookie jars rather than bank vaults.

Can the wealthy do it better?

It was partly that lack of general confidence that inspired celebrity philanthropists this year to pledge eye-popping amounts to charities — from Buffett’s $30 billion plus to the Gates Foundation, to Richard Branson’s $3 billion for global warming and Google’s billion dollars for big-problem solving. All champion the view that well-funded and well-run private charities can help reassure contributors by running philanthropies like their businesses.

Many veterans of the philanthropy sector applaud their initiative, but they argue that those gifts fail to address the underlying sources of the public’s eroding confidence – abuse of trust, lack of accountability and, sometimes, a lack of concrete results.

"United Way, the Nature Conservancy, Rick Santorum’s foundation – those things all add up," said Rick Cohen, former director of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, referring to charity scandals that linger in the public’s mind. "They chip away at the public’s sense of trust."

Kevin McCarthy, CEO of the United Way of Inland Valley in California, argues that the perception that financial shenanigans are widespread is at least partly due to skewed media coverage and selective memory, noting that he still hears regularly about the 1992 scandal surrounding United Way CEO William Aramony.

"We still hear about the Red Cross charging for donuts in World War II," he said. "The thing about those stories is that … they remember the sensationalism but not the facts. ... What Aramony did didn’t affect the local groups. He and two other people plundered from shell organizations. But nobody ever hears that. You just hear, ‘Oh, you guys couldn’t keep your own house clean.’"

Possible misconceptions aside, Congress has grown increasingly concerned over abuse of nonprofits’ tax-exempt status – in some cases by lawmakers themselves – and attempted to crack down on such practices.

"Americans are very generous with their donations," Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, the soon-to-be former chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, said following Senate passage of the Pension Protection Act of 2006 in August. "They deserve to know that their money helps the needy, not the greedy."

Will tighter restrictions work?

Among other things, the act, which will take effect early next year, targets the practice of taking overly generous deductions for donated items; requires nonprofits to disclose unrelated business income and pay taxes on it; and adds new reporting requirements for the smallest nonprofits.

But Marion Fremont-Smith, a senior research fellow at Harvard’s Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations, said reforms will accomplish little unless they are accompanied by more aggressive enforcement.

"If we’re going to rely on the IRS, we have to give them more funds to do it," she said. "They’re absolutely overwhelmed. … The people there have been on hiring freezes for years. There’s plenty of good law there … (and) I think if people felt there were audits and more effective enforcement, there’d be fewer bad actors and certainly more confidence."

While Congress has not provided additional enforcement funding, Grassley has pressed the IRS to step up enforcement against abuse of tax-exempt status, particularly the creation of nonprofit groups to receive federal grants and engage in political activity.

The IRS did not respond to a call seeking comment on whether the agency plans to aggressively target such abuse, but it issued a memo in February warning churches and other nonprofits against "directly or indirectly participating in, or intervening in, any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for elective public office."

The agency said any nonprofit engaging in such activity would risk losing its tax-exempt status.

While the erosion of public trust is a concern across the philanthropic spectrum, smaller charities are simultaneously facing another new challenge: An increasingly confusing array of charitable choices.

An expanding universe of choice

According to the 2007 charity almanac, approximately 1.4 million nonprofit groups were registered with the IRS in 2004, the most recent year for which complete data were available – a 27 percent increase over 1994. (Those organizations play an increasingly important role in the economy, accounting for 5.2 percent of the nation's economic output and paying 8.3 percent of all U.S. wages and salaries, it said.)

The increasingly crowded field is good for the charities with household names like the United Way and the American Red Cross -- donations to the country’s largest charities are up 13 percent from last year – but it has left many smaller nonprofits struggling to survive.

"The competition is fierce, and organizations that in the old days might have gotten along just fine might find someone else is eating their lunch," said McCarthy, the United Way CEO in Southern California. "The larger organizations -- megachurches, universities, hospitals, major philanthropic organizations – they’re all getting better at how to do this … but the smaller organizations, they don’t have that kind of horsepower."

McCarthy said that competition also has changed the equation for the United Way, which parcels out money it collects to a broad array of charities.

"When we have an organization providing a needed service, and all of a sudden they have to close their doors because they have no money … we have to deal with how can we continue to service those clients," he said. "So we don’t just have to raise money, we have to invest ourselves in the health of those partners. We have to do board training, network training and get big foundations to look at small organizations. It’s no longer a matter of just looking at how well they do their programs."

Private groups like GuideStar and Charity Navigator have tried to cut through the white noise by ranking nonprofits based on their tax returns, called Form 990s. These rankings show what percentage of money raised by a nonprofit goes to programs vs. overhead and fundraising, and give higher ratings to those organizations that funnel more money to programs.

Are rankings reliable?

But some charity experts say the rankings have added to the confusion by oversimplifying the financial realities of philanthropy and failing to recognize that smaller charities often need to devote more resources to fundraising.

That leads many donors to try to "bypass the infrastructure," said Eugene Tempel, executive director of Indiana University’s Center on Philanthropy.

As an example, Tempel said that during the Hurricane Katrina aid effort, "Voices were raised about giving directly to victims. … (In response), nonprofits talked about an imaginary donor who takes $100, drives to Louisiana and hands the money to a victim. All the money went to program, right? Wrong: The donor incurred costs to get there, to get back … and the spending was considerably more than $100. Charities bear those costs (and) critics don’t think about that."

The ratings also have helped give rise to a practice in which donors target their gifts to a specific need, hamstringing a charity that is battling to meet its operating costs, said Cohen, the former director of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy. He compared the practice to "buying stock in GM and saying I want my money only to support hubcaps."

Many in the charity world see a single underlying issue behind such concerns – the simple matter of trust.

And they say it is an issue that must urgently be addressed if U.S. charities are to harness what former President Bill Clinton described in the keynote address at this month’s Slate 60 charity conference as "the unprecedented capacity of ordinary people to collect and direct their funds in a way that gives them about as much power as the wealthiest people in the world."

Success is not a foregone conclusion, warns Egger, who runs the food bank in the nation’s capital.

"Nonprofits always had a safe warm spot in the public's heart," he said. "Now that is in real jeopardy."