First you see the faces of Holocaust survivors in stark photographs. They set the stage for the horrors to come, displayed in blunt but richly textured wall hangings at the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage.

“Sometimes — I don’t know if it’s right or wrong — I feel guilty myself that I survived,” said Polish-born Sylvia Malcmacher, 80, one of the subjects in a black-and-white photo by Herbert Ascherman Jr. She lost her parents and both sisters in the Holocaust.

Still, she said, “I’m thankful. I can talk about them. Otherwise, no one would even mention their names.”

The side-by-side exhibits — “Threads of Remembrance: Artistic Visions of the Holocaust” — open Wednesday and continue through Feb. 18 at the museum in the Cleveland suburb of Beachwood.

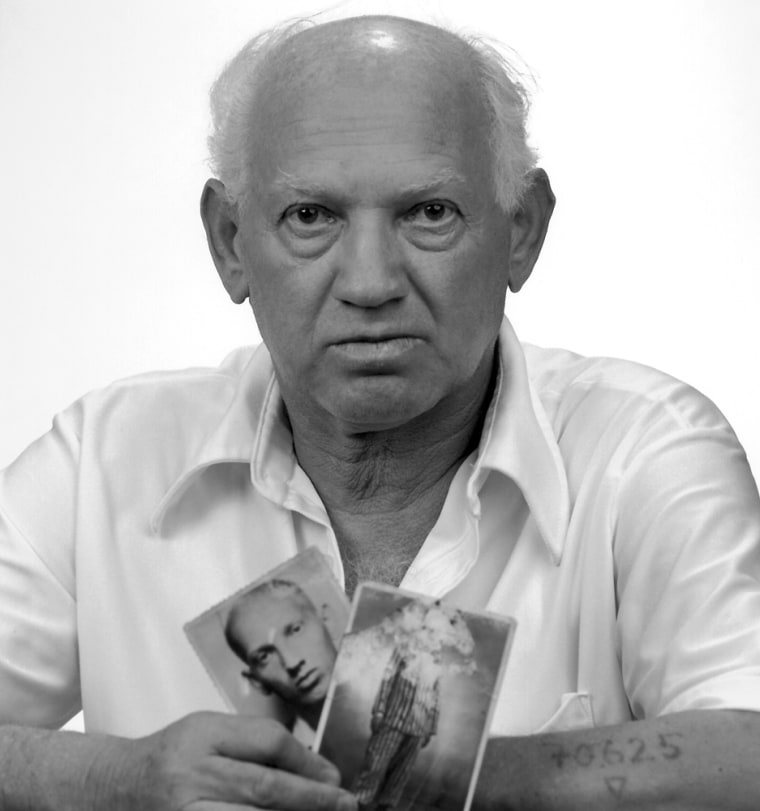

Visitors will first see “50 Faces” — a corridor exhibit of Ascherman’s photographs of people, all from the Cleveland area, who are Holocaust survivors, former prisoners of war and soldiers who liberated the death camps.

Inside the exhibit area, Judith Weinshall Liberman’s “Holocaust Wall Hangings” are mounted on dimly lighted walls and black sheets. Camp names, deportation routes, poison gas, guard dogs and death and barbed wire everywhere are depicted in appliqués, stencils, beads, embroidery, painting and sewing.

One hanging, in bright red and black, shows a forearm extending from an open-door oven.

“It’s unbelievable what happened,” Malcmacher said. “I don’t belief it myself that I went through this and I survived.”

According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, nearly two-thirds of Europe’s 9 million Jews died during the Nazi regime.

The photos and hangings have been shown in other cities, but this is the first time they have been displayed together.

Ascherman, 59, who has devoted his career to portrait photography in Cleveland, made no attempt to brighten the documentary-style, unsmiling faces when photographing some of the estimated 1,000 Holocaust survivors in the city.

“When you look at their eyes, there is a crazed look. It’s not normal. It’s different,” he said during a preview tour of the exhibit. “The normalcy was taken from them.”

Although the photos capture the people as aging adults, some survivors display number tattoos required by the Nazis and others hold wartime era pictures of themselves. One man wears a striped camp-style cap that looks out of place with his white shirt, jacket and tie.

Liberman, 77, who lives in Westwood, Mass., was born in pre-Israel Palestine and had a Polish nanny who emigrated in 1938 and lost her parents in the Holocaust. Liberman dedicated the hangings to her late husband, Robert Liberman, who visited the Dachau camp with the U.S. military in 1945 as a 21-year-old “and never forgot.”

“I am just a human being and an artist and, as such, I feel I have a special responsibility to speak out about a subject close to my heart, namely, man’s inhumanity to man, whether evidenced in the Holocaust or elsewhere,” she told The Associated Press in an e-mail.

Liberman, whose works are well-known in the Holocaust art and academic community, said the hangings, some as big as bedspreads, were meant to evoke the Nazi banners flying over occupied Europe.

Ori Soltes, who teaches art and theology at Georgetown University and formerly directed the B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum in Washington, thinks the soft materials Liberman uses provide an important contrast to the Holocaust tragedy.

“Using that kind of material for something which is so harsh and hard-edged to my mind is sort of an interesting conceptual leap,” Soltes said.

Rabbi Richard A. Block of The Temple-Tifereth Israel, founded in Cleveland in 1850 and one of the nation’s oldest reform congregations, said the exhibit deals with a solemn subject but ultimately reflects hope because “notwithstanding everything, the Jewish people live, there were liberators, there were righteous Gentiles” who aided Jews.