Powerful forces are exerted on the shoulders of birds where muscles converge, and scientists have long wondered why the joints don't dislocate. As it turns out, a short band of tissue is the key to this delicate balancing act.

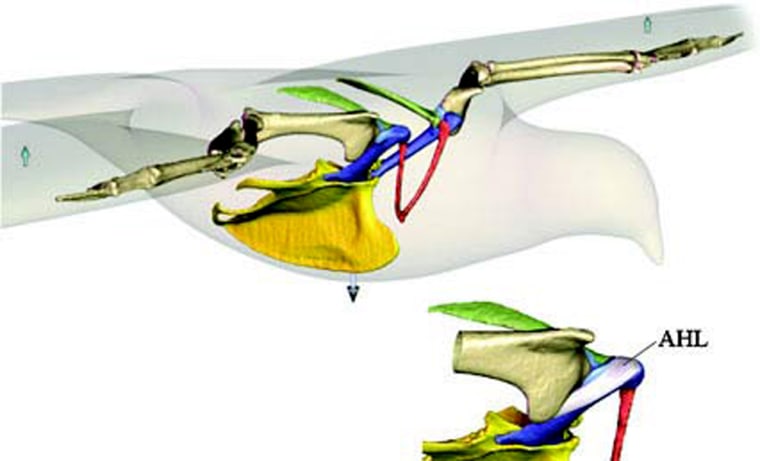

Using CAT scans, scientists at Brown and Harvard universities made a virtual skeleton of a pigeon and then calculated all the forces involved. Neither the shoulder socket nor the muscles could keep the wings stable.

The key, they found, is the acrocoracohumeral ligament, a short band of tissue that connects the humerus to the shoulder joint. The ligament balances all of the converging forces, from the pull of the massive pectoralis muscle in the bird's breast to the push of wind under its wings.

Curious if the same was true of ancient animals, the researchers put some alligators on a treadmill and studied their gaits and used X-rays to make more computer models. The ancestors of modern alligators were closely related to birds.

They found that alligators use muscles, not ligaments, to support their shoulders. A look at fossils of Archaeopteryx, thought to be the first bird, revealed its flight mechanism to be unlike the pigeon, too.

"Our work also suggests that when early birds flew, they balanced their shoulders differently than birds do today," said study leader David Baier, a post-doctoral research fellow at Brown. "And so they could have flown differently. Some scientists think they glided down from trees or flapped off the ground."