Can you remember your 10th birthday—the cake, the anticipation of opening presents?

The twins, Mara and Nicole Dosso will sadly never forget their tenth. It was December 3, 1997.

Mara Dosso: I just remember that we woke up and then he sang us "Happy birthday."

He was their dad, 35-year-old Frank Dosso.

Dennis Murphy, Dateline correspondent: Any special plans for that day that you remember?Nicole Dosso: That night, we were supposed to have cake and coffee with our grandparents and our aunt and uncle and my mom and day.

But their father was late getting back from work. It was unlike him. Frank had promised his wife Maria he’d bring home Chinese for the party.

Maria Dosso Jacoby, Frank Dosso's wife: At a quarter to 6 p.m. I called him because I was actually annoyed with him. I was gonna say to him “What are you? Why aren’t you home yet? Of all days, you know, you’re coming home late.” And there was no answer already.

Maria began to worry. Maybe there’d been car trouble, worse, an accident.

Frank worked with his father and his sister’s husband at a manufacturing business in central Florida, near Tampa. They made the kind of conveyor systems you see in dry cleaners that retrieve garments.

But now—on the twin’s birthday—it was getting late. The last time they talked, Frank told Maria that his sister Diane would be picking up him and her husband George Patisso. They’d all arrive together.

But where were they?

Maria Dosso called her husband’s parents, Phil and Nicoletta. They hadn’t heard from their son or daughter either. So the elderly Dossos got in their car about 6:30 p.m. and drove 20 miles to the shop, Erie Manufacturing.

The lights were on. They saw their daughter, Diane’s, car parked out front...

Nicoletta Dosso, Frank Dosso's mother: I walked in, the door was open. It was not locked...I walked in there… and I saw Diane. And I said, “Oh, my God. Diane, who did this to you...who did this to you?”

The parents saw their daughter, Diane, first in the hallway, her legs crumpled beneath her in a pool of blood. She’d been shot twice in the head.

Around the corner, more. Diane’s husband was murdered execution-style.

His body was slumped by Dosso’s longtime business partner, George Gonsalves.

And a few feet away lay their son, Frank Dosso—Maria’s husband, the twin’s father—like the others, shot in the head.

Nicoletta Dosso: So, when I walked in, I closed Diane’s eyes. I said, “Diane, I was the first one to see you. And I’m the first one to see you going.” And I closed the eyes.

It wasn’t long after, Frank’s wife, Maria, arrived to flashing lights and strung yellow crime-scene tape. Her father-in-law delivered the unbearable news.

Maria Dosso Jacoby: Phil came over to me and he held me so tight it hurt. He held me so tight, and he told me, “Maria, we lost them.”

Four dead. Four murdered.

An extended family’s gaping horror became an urgent criminal investigation.

Polk county Florida, the town of Bartow, had never had a mass murder.

There were so many scenarios to run down. Was it an act of passion, perhaps, or revenge? Was Diane, the Dosso’s daughter — who happened to be a local prosecutor — the target?

Local police quickly called on the help of agents from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement—the F.D.L.E—the state’s counterpart of the F.B.I.

FDLE agent Tommy Ray was put in command of a state-local task force.

Tommy Ray, Florida Department of Law Enforcement agent: When we first started the taskforce and we started looking at this, there was a FBI profiler. He stated that this was a career case. And I asked, ‘What do you mean, a career case?’ and he goes, “Hopefully, you’ll solve this. But, you’re not gonna solve this overnight, you know? This is gonna take a long time.”

Agent Ray knew all about crimes taking a long time to crack. In his 25 years on the job, he had a well-earned reputation as a cop with a knack for solving stone cold cases.

Hopefully, the Erie Manufacturing massacre wouldn’t be one of them.

Detectives began their investigation by looking at what the crime scene itself could tell them, the warren of offices and hallways in the shop, where forensic technicians had recovered 12 bullet casings, eleven of them .22 calibre, the other a .32. That meant two different guns had been used.

Ray: Initially, we thought there was more than one shooter. We thought there was probably two to three suspects.

From the trajectory of the wounds in the victim and resulting blood spatter no more than a foot or so off the ground, the investigators concluded that the three men had been forced to their knees or put on the ground and killed with a .22.

Ray: You could see how someone in the doorway with a firearm could hold three guys at bay, maybe force them down and as they’re getting down, you know, start shooting.

Diane, the evidence suggested, had apparently come in after the initial murders, been chased by her killer, and grabbed from behind by the hair. She’d been shot in each temple with both a .22 and a .32 caliber handgun.

But fingerprints? DNA? Hair? Fiber? The killer or killers hadn’t left a trace.

There was a chair with a dusty footprint of a man’s shoe on it and a drop-ceiling tile overhead that had been moved.

But like so much else about the puzzling scene, detectives didn’t know what to make of it.

Four families were shattered. Maria Dosso was suddenly the single parent of three young girls.

Maria Dosso Jacoby: I remember we were all in my and their father’s bed just holding each other. And I didn’t even want to change the sheets for a while because that’s the bed that Frank had slept in. I just wanted to hold on to whatever I could. (crying) And I think the girls wanted that too. Murphy: How did you tell the girls?Maria Dosso Jacoby: I told them one by one. I remember Nicole was the first one. And I told her, I said, “You know, daddy is dead.” And the first thing Nicole asked me, “Did Nelson Serrano do it?”

The three partners who made up Erie Manufacturing were like family. They danced at the weddings of one another’s children.

In 1985 when Frank Dosso married Maria, business partner Nelson Serrano was there celebrating with his wife.

Serrano, originally from Ecuador, had been a middle-man who sold the garment conveyor systems that Erie made to big customers.

Eventually, he bought into the company and was welcomed as a full partner of Phil Dosso and his longtime friend and co-founder of Erie, George Gonsalves.

With Serrano’s flair for sales, and the original partners knowledge of the nuts and bolts of manufacturing, Erie grew into a multi-million dollar family operation by the mid-90s.

The aging partners were slowly making way for their children to take over the company.

Frank and Maria Dosso had moved down from the New York area so he could be groomed to take his father’s place.

Serrano put his son on the payroll as the bookkeeper.

But there was something about Serrano that spelled trouble to Frank’s wife, Maria.

Maria Dosso Jacoby, Frank's wife: I always got the impression that he thought that he was better than everybody else.

And she wasn’t the only one that felt that way. By the summer of 1997, a long simmering dispute boiled over into an all-out war among the partners. There were allegations that Serrano stole a quarter million dollars.

After lawsuits filed and one shouting match too many, the founding partners, Dosso and Gonsalves, fired Serrano and his son and changed the locks to the office.

But Serrano didn’t leave quietly. Within weeks of being ousted, he tried to force his way back into the building. Partner George Gonsalves called the cops.

911 callGonsalves: Somebody’s breaking a door down.911 operator: Is this someone you know, former employee.Gonsalves: Yeah, former employee. 911 operator: What is his name?Gonsalves: Nelson Serrano.

Then, six months later, December 3rd, 1997, came another 911 call from Erie Manufacturing: Four dead, shot execution-style.

Given Serrano’s stormy relationship with his partners, homicide detectives asked him to give a taped statement the day after the killings.

Frank Serrano’s taped statement: ...I have no idea what really happened, where it happened, when it happened, how it happened.

Serrano talked to police willingly, speculating on how the murders went down.

Serrano: There were many people involved. I mean, one guy is gonna go over there and knock off four people?...

Serrano told police he was in Atlanta -- 500 miles away from Erie Manufacturing on the day of the murders, holed up in his hotel room, door locked, drapes pulled, suffering from a migraine.

And an airport hotel security camera seemed to bear his story out.

Here he is on tape at an Atlanta LaQuinta Inn in the lobby around noon the day of the massacre. He walks into frame again about ten o’clock that night.

Agent Tommy Ray’s team, of course, had his alibi checked out.

Tommy Ray, FDLE agent: When we got a phone call from the two detectives that went to Atlanta, they said, hey we got him here in the afternoon. He couldn’t have done it.

But that didn’t mean detectives thought Serrano’s hands were clean of the crime.

Ray: When we believed that Nelson was in Atlanta, we thought that he hired someone for a contract killing.

For all the red flags flapping around him, detectives never could get enough to arrest Nelson Serrano.

Years went by.

The twins had others birthdays.

And the father of one of the murder victims, Diane’s husband George, flew to Florida to demand answers from prosecutors but got unpromising replies.

George Patisso: They told us, even though they been working on it for a couple of years and they’ve had many leads, we just want you to understand there’s a possibility that this case will never be solved.

But Agent Tommy Ray—the chief investigator—hadn’t thrown in the towel. In fact, he made a promise to the victim’s families, including the mother ofvictim George Patisso.

Maryanne Patisso: He says he would never retire until this was solved.

But tenacity and resolve weren’t the same thing as results.

Here was the detective’s problem: he’d come to believe that it was Serrano himself who walked into Erie manufacturing and shot the four...

But Nelson Serrano’s alibi had him up here at the Atlanta hotel on noon of that day—the killings happened about 5:30 in the afternoon in Florida.

So how did Serrano get from Atlanta to Erie manufacturing in Florida and back to Atlanta in time to be photographed by the hotel security camera again at 10 p.m. or so?

He had to fly, obviously, but only two airports in central Florida made sense for the very tight timeline of the crime to work. He either flew into Orlando or into Tampa.

All theory. Meanwhile, the murder investigation at Erie Manufacturing was getting colder and colder.

Dennis Murphy, Dateline correspondent: This case has then hit a brick wall, huh? Ray: As far as a brick wall, we were still doing background on any and everybody connected to Nelson Serrano.

One of those people connected to Serrano was a nephew in Florida named Alvaro Penaherrera. The detective could not figure out why Serrano had called his nephew so frequently around the time of the murders.

Ray: The day of the homicide, Nelson had called Alvaro like at 7:53 a.m.. There was a series of phone calls that connected Alvaro to nelson.

Then, Detective Ray’s team came up with a bingo moment, the discovery of a credit card transaction for Serrano’s nephew on a most interesting day and for the detective in a most interesting place.

Ray: He had rented a car on December 3rd of ‘97, the day of the homicide. It was rented in Orlando, but yet turned in Tampa.

When the detective brought the nephew in for questioning, Tommy Ray says the young man lied about the car rental at first, then caved, when he feared he might become a suspect in the mass homicide.

Ray: His uncle, Nelson Serrano, called him and said, “Look, I need you to rent a car for me for December 3rd. I’m having a Brazilian mistress that’s flying in, and I don’t want my wife to find out about it.”

But another problem: if Serrano flew to Orlando that day to pick up a rental car from his nephew, he didn’t fly under his own name.

There was no Serrano on the passenger manifest of the only flight that day from Atlanta that fit the timeline.

But a few weeks earlier in a casual conversation, the detective learned from the Dosso family that Serrano had a child from an early marriage who was rarely mentioned.

Murphy: And what was a name associated with that child?Ray: Juan Agacio.

Agacio! That was a name on the passenger manifest from Atlanta to Orlando, the day of the murders. An Agacio who paid cash for a round-trip ticket and never used the return portion.

And what’s more, someone named John White had done the same thing: bought a round trip ticket for cash from Tampa to Atlanta for the evening of the murders, and like Agacio, he’d never used the return fare.

Agacio...White...a nephew instructed to arrange for a rental car in Orlando, one dropped off at Tampa airport...

The pieces were snapping into place for Tommy Ray.

Here’s what Ray was thinking. Serrano, using an alias, flew from Atlanta to Orlando, picked up the rental car and drove to Erie Manufacturing and committed the murders.

Then he drove to Tampa, dropped the car off and returned to Atlanta using another alias. All in the 10 hours allotted. All done in a calculated way to cover his tracks.

Murphy: So do you go to the prosecutor at that point and say, “We got it. Let’s go to the grand jury. Let’s get us an indictment?”Ray: Yes.Murphy: And he said?Ray: He said, “You’re close, but you’re not there. He needs some physical evidence, something placing Nelson back in the area on the day of the homicide. We just have to keep digging.

Digging: it’s in the detective’s DNA.

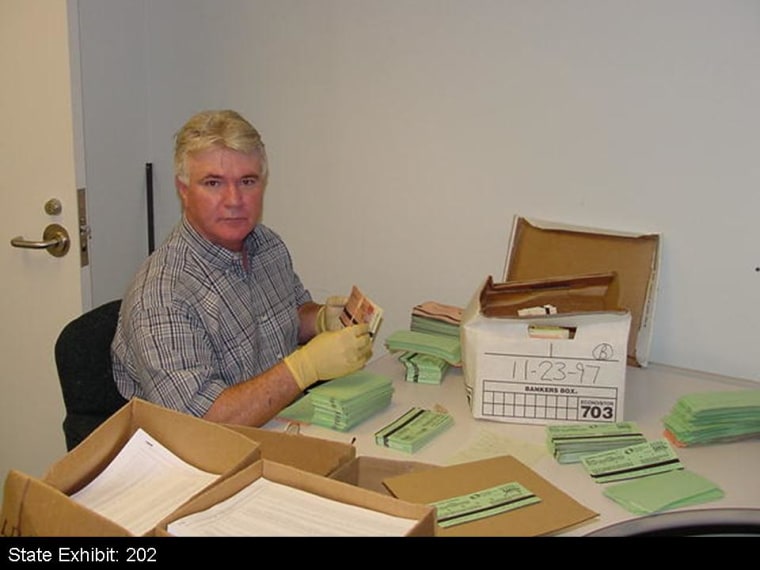

And now the Erie Murders would find him digging through a box of moldy old receipts.

Like Little Jack Horner, Tommy Ray pulled out a plum.

The company made garment conveying systems and sold them for millions every year.

In the hallway and business office of Erie Manufacturing, four people, three men and a woman, had been shot dead.

Florida state detective, agent Tommy Ray, thought he could prove that Nelson Serrano, an ousted business partner had done it, even though he claimed to be in Atlanta that day and a hotel security camera there backed his story up.

Dennis Murphy, Dateline correspondent: He’s got a good alibi, doesn’t he. He’s 500 miles away?Tommy Ray, Florida Department of Law Enforcement: He had planned it out well.

Detective Tommy Ray had evidence indicating Serrano’s nephew had left him a rental car in the Orlando airport parking garage.

He’d put the ticket to get out of long-term parking in the visor.

That meant Serrano had to have touched it.

But where was that years-old ticket now?

Did it still exist?

The detective had to get his hands on it.

But there was a big problem at the airport records office.

Ray: Initially a couple of the other detectives were told that those particular tickets had been destroyed by a storm.

But Tommy Ray kept on coming. That parking ticket might be his only shot at proving that Serrano had indeed put foot back in Florida the afternoon of the murders. Insisting.

Ray: I said, “I wanna see where the tickets were destroyed. I wanna see, you know, what you have.”

And as the detective was getting ready to go to the airport, he got a call back from airport officials saying, sorry, they were wrong about those tickets being damaged in the storm. And they were, in fact, intact and waiting for him to sift through.

Murphy: So now you’re on the flip side of this luck, huh?Ray: Well, divine intervention plays a big part in here.

Ray and his team tediously poured over hundreds of old parking slips.

Finally there it was: December 3rd 1997 a car had left the long-term parking garage at 3:49 pm and printed right on the receipt, the license plate of the rental picked-up by Serrano’s nephew.

And when Lynne Ernst, the fingerprint expert at the state crime lab, started processing that three-year old parking receipt, a wondrous thing happened for Tommy Ray’s blossoming theory of the case.

Ray: Lynne calls up, and she goes, “Tommy,” she goes, “I got some fantastic news.” And the fantastic news was we had prints of Nelson Serrano.

The fingerprint proved Serrano was in Orlando, Florida on December 3, 1997, just an hour and half drive from Erie Manufacturing, not in a hotel room in Atlanta nursing a migraine.

Ray: I knew at that point there was no doubt there was more than enough for an arrest and an indictment against Nelson Serrano.

And in May 2002, almost four and half years after the murders—Tommy Ray finally got his indictment - four-counts of first-degree murder against Nelson Serrano.

Murphy: But there’s a problem.Ray: Ahh, Nelson fled to Ecuador.

Federal officials said the chances of extraditing Serrano, an Ecuadorean national, would be slim to none.

The detective’s superiors told him to forget about it.

Murphy: When somebody tells you to forget about a case, I mean, is that—is that an order that sticks?Ray: Not really, especially this case.

But orders were orders—and Ray got new ones, a reassignment to Miami.

But luck followed the detective to Miami where a chance meeting with an Ecuadorean colonel soon changed everything.

Ray asked the colonel to convince his government to extradite Serrano, and told him why he wanted him back so badly.

Ray: After he saw the violence and what Nelson Serrano had committed, he said, “We’ll work it out. We’ll get him out of Ecuador.”

And that’s just what Tommy Ray did with the full cooperation of Ecuadorean authorities. When officials there discovered Serrano had actually been a U.S. citizen for years, they deported him to America in the custody of Detective Ray.

In September, 2002, Nelson Serrano walked into a Central florida courtroom and pleaded not guilty to the murder charges.

After a snarl of legal delays, in September 2006, nearly 9 years after the murders—Serrano finally sat before a jury: the accused; in a first degree murder death penalty case.

Prosecutor John Aguero (in court): That man sitting right there murdered four people.

In court, Tommy Ray sat a few feet away from Nelson Serrano...

The families of the four victims packed one side of the courtroom, as the prosecutor, John Aguero, called Phil Dosso to recount the history of bad blood with Serrano.

Phil Dosso, Serrano's former business partner: He said, “I don’t want to see your face anymore because I can kill you some day.”

The voice of the mother of two of the victims took jurors back to the horrors of the night captured on that 911 call.

The prosecutor introduced the gruesome crime scene photos, bullet casings and bodies that accompanied the story he told the jury about a onetime business partner’s homicidal revenge, the bitter loser in a fight for control of the company.

And when jurors went to tour the murder scene itself, the prosecution explained its theory of why that ceiling tile had been moved and why there was a dusty footprint on the chair beneath.

Employees testified that Serrano, a gun enthusiast—kept handguns in his office—and MAY HAVE stashed at least one away in the drop ceiling.

Aguero: The same day you see him getting something out of the ceiling is the day you see the gun?Employee: Yes.

Behind the tile, likely, prosecutors say where he kept the .32 — one of two guns used that night.

Aguero: There’s only one person that we’ve heard about that would have an interest in that ceiling tile. And that’s a guy that maybe left a gun up there that he don’t want the cops to find.

And as for the dusty shoeprint? Not definitively Serrano’s but very much like a shoe he’d once owned and experts examined.

Aguero: The wear pattern is consistent with the shoe that stepped on that vinyl chair in December, 1997.Expert: Absolutely.

Prosecutors knew they’d have to shred Serrano’s alibi that he was in Atlanta for a business trip. They laid out its evidence for Serrano being in Florida that day.

They called the nephew who rented the car for his uncle and he told a damaging story about him. The day after the murders, he said his uncle ordered him to retrieve that same car in the Tampa airport parking garage and drop if off with the rental company.

Weeks later, the uncle told the nephew to keep his mouth shut about the incident.

Alvaro, nephew: He looked at me straight in the eye and said, “You can’t say anything about this, you know that. Because cops are not gonna buy I was in Orlando with a lover. They’re gonna frame me. And they’re going to try and do something to me.”

And the prosecution played maybe its best evidence: the Orlando airport date-stamped parking ticket with Nelson Serrano’s fingerprints on it.

Aguero: There is no doubt in your mind that man left that fingerprint on that card? Expert: No sir.Aguero: The only way it could’ve gotten there is if Nelson Serrano’s index finger touched the card?Expert: Yes.

And prosecutors especially wanted jurors to listen closely to that taped statement Serrano gave police a day after the murders.

It was weirdly as though he were reciting the state’s own theory of the crime.

Serrano (taped statement): ...I don’t think it will be robbery. I think it will be mostly some resentment or some revenge, somebody getting fired, somebody getting cheated. Somebody—I don’t know.

And listen further, urged the prosecutor, to what Nelson Serrano had to say about why Diane Patisso was murdered when she went to pick up her husband and brother.

Serrano: ... She, uh, comes everyday to pick him up...then I assumed myself, I says maybe, maybe she walked in, in the middle of something.Aguero: He says, “I think the girl walked in on something.” Wait a minute. Nobody’s been in this crime scene. Nobody knows where these people were and he’s making this statement.

The investigators never did find the two handguns used in the killings... but as it rested its case, the prosecution was comfortable in thinking it had convinced the jury they could only have been in the hands of Nelson Serrano...a onetime partner, the prosecutor argued, with a wounded pride and a murderous rage.

The heart of Nelson Serrano’s defense was simple: There’s no evidence to prove that Serrano ever set foot in Erie Manufacturing the day of the murders.

Dennis Murphy, Dateline correspondent: What was the biggest obstacle in trial, you had to overcome here?Bob Norgard, defense lawyer: The biggest obstacle is four dead people, It’s a lot easier for jurors to find somebody guilty on "maybe" evidence. They’re not supposed to.

Defense team Bob Norgard and Cheney Mason were relentless in their cross examination of prosecution witnesses, starting with the crime-scene technicians who gathered evidence...12 bullet casings, for instance, that told them nothing about who loaded the guns.

Norgard (in court): With respect to the casings, no fingerprint evidence linking those casings to Mr. Serrano?Sgt. Brooks: That’s right.

No Serrano fingerprints found anywhere around the crime scene.

Norgard: Not a single fingerprint was linked to Mr. Serrano in that building, isn’t that true?Sgt. Brooks: None of the latents from the building were linked to him.

The dusty footprint on the chair seemed to be Serrano’s shoe size but...?

Norgard: Can you tell me how many shoes there are that match? Oral Woods, shoe expert: No, I cannot.Norgard: I mean, a million, two million, ten millions? Hundred million? Do you know?Oral Woods, shoe expert: I really don’t know.Murphy: This is all part of a circumstantial case. You have to believe each link in the chain to get him to make that footprint in the chair.Cheney Mason, defense attorney: What is the theory here that there’s three men in there, 200-plus—lbs.each, “’Excuse me fellas, I need to borrow this chair so I can climb up there and get a gun and shoot you with it?” How silly is this?

Serrano’s son, Francisco, had been called by the prosecution but the defense used him to flip the tables, testifying that it was his father’s partners who actually stole business money from him, not the other way around.

Francisco Serrano, Nelson Serrano's son: Well, a million dollars had disappeared and George and Phil were not willing to tell us what they did with the money.

Then the defense went after the busy here, there and everywhere of Serrano’s alleged travels the day of the murders, in and out of airports, boarding planes, driving around. How come no person or camera saw him?

Norgard: Not a single witness was found who saw Mr. Serrano leave that hotel, drive to the airport, park at the airport and get on a plane? isn’t that true?Tommy Ray: That’s correct.Norgard: You’re sure that there are no videotapes from Atlanta, Tampa or Orlando showing Mr. Seranno anywhere near those airports on this day, isn’t that true? Parker: I have no personal knowledge of any tapes of that nature, no sir.

And in that day of travel, the defense argued that there just wasn’t enough time for Serrano to have pulled off the crime he was charged with.

Leaving the Orlando airport garage at 3:49 p.m. as the timecoded parking record indicated...

Detective Tommy Ray testified it had taken him an hour and fifteen to drive from the airport to Erie Manufacturing.

That would have put Serrano at the shop just after 5 pm, leaving him only fifteen minutes to kill four people.

Murphy: Your important point of the timeline is: look when the last victim is killed. Has to be 5:20.Cheney Mason: You’d be stretching your imagination to believe you could drive that distance, in the traffic, and get there, and be able to commit this crime. I do not think so.

And the last part of the timeline, the defense argued was even more implausible.

In less than half an hour, Serrano would have had to get off a wide body jet, exit Atlanta airport—one of the busiest in the world—and arrive back at his hotel five miles away. All in time to be photographed looking up at that surveillance camera.

Mason: I challenge anybody to show me, I’ll pay them a million dollars if they can do it.Murphy: If they can do it in the time alloted?Mason: 28 minutes. Can’t happen. Didn’t happen.

The biggest hurdle for the defense was just ahead, starting with the testimony given by the nephew that he’d arranged a car rental at Orlando airport for his uncle on the QT.

The defense grilled the nephew, portraying him as someone who was just interested in saving his own skin.

Defense attorney: You weren’t just someone that they wanted to question as a witness, but that they had you pegged as a suspect in the quadruple homicide. Isn’t that true?Alvaro Penaherrera: Yes.Defense attorney: You wanna tell the jury how much that scared you?Alvaro Penaherrera: I already said I was very scared.Defense attorney: Yes. They broke you down and got you to change your story, right?Alvaro Penaherrera: Yes, I changed the story.

In a circumstantial case that the prosecution had the burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt, it came down to one crucial piece of evidence, nothing less than the foundation of the prosecution’s charges against Nelson Serrano: his fingerprint on that parking ticket that put him in Florida on the afternoon of the murders.

The state had put on three fingerprint experts. Two agreed that it was Serrano’s, but the third surprised the prosecutor when under cross examination he testified he wasn’t entirely convinced.

Expert: I had—and I still have reservations—about this particular latent.

An expert in the field—the prosecution’s own witness—telling the court he had reservations about the fingerprint?

Why, he wondered, was a finger from Serrano’s right hand on the ticket and not one from his left?

Expert: If you’re wearing a seatbelt, it’s extremely restricted, where you are reaching across your body, between your body and the steering wheel, to hand it to someone over here.

The defense leaped into the crack in the prosecution’s case and floated the possibility that the all important fingerprint was bogus, forged by person or persons unknown to implicate Serrano in the crime.

Mason: Were you able to determine from them anything about the veracity of those prints?Expert: No, I can’t...Mason: Can fingerprints be planted and not detected even by experts? Expert: I had a great deal of experience with the so-called forged and altered fingerprints.Murphy: Are you saying that the cops did it?Mason: I don’t know who did it.Murphy: The cops planted a bogus fingerprint on this—Mason: There’s a high likelihood that that print was an act of desperation after years of frustration in this very high profile, very significant case.

Had the defense made the jury wonder? Had they put some cracks in the prosecution’s theory of the crime?

After 60 witnesses, 400 exhibits and five weeks of trial, closing arguments were at hand.

The defense going first.

Bob Norgard, defense attorney: Not a single person on the planet earth, not one single person has put Mr. Serrano at Erie Manufacturing on December 3, 1997.

The prosecutor countered that Serrano had a volcanic grudge against his former business partners and the parking ticket and the long chain of circumstantial evidence was the proof that he was the killer.

John Aguero, prosecutor: It’s getting harder and harder and harder to think that all of these things could just be coincidences and they happen to poor Mr. Serrano. That’s one diabolical son of a gun sitting over there.

It was now up to a jury to decide.

No juror had bargained for this when they got their summons...potentially a death penalty case.

And looking over at the defense table and seeing Nelson Serrano...the accusation didn’t seem to fit.

Juror Lucy: It definitely didn’t look like someone that would—that would do that.

We gathered eight of the twelve jurors to talk about the case, starting with the prosecutions four-hour opening statement that left some jurors scratching their heads.

Dennis Murphy, Dateline correspondent: It’s a very complicated story, what happened at this business, and there are a lot of names. Juror Lucy: At the beginning, it didn’t make sense.Juror Wayne: There was some holes in it.Murphy: And the defense says, “Look, I’m not gonna make this easy for you. My client, the defendant, Nelson Serrano wasn’t at that place. You can’t put a gun in his hand. There’s no hair, fiber, fingerprints, DNA, there’s nothing to indicate that he was in that place on that day. Juror Cheryl: Well, they had me when they were saying, “Well he didn’t have a gun. he didn’t have this. you can’t prove that he was there.”

More important than the assertions from both sides was the evidence in the case. A visit to the crime scene was a jolt for jurors. They literally walked in the killer’s footsteps at Erie Manufacturing.

Murphy: Lucy, was it chilling for you?Juror Lucy: That definitely was.Murphy: To walk into this place finally?Juror Lucy: Especially the office where the three gentlemen were. And just being in there, I just wanted to get out.

There they saw the ceiling tile that had been moved...where Serrano was accused of hiding a gun used in the murders.

But as for a supposedly tell-tale dusty footprint on a chair beneath that tile... some jurors dismissed it as evidence.

Juror: Shoe made no difference, whatsoever, to me.

But what preoccupied jurors most was the tight timeline of the prosecution’s theory of the crime— just 10 hours for Serrano to fly, drive, murder, fly again and be back in Atlanta photographed by a hotel security camera.

Murphy: Complicated scheme, wasn’t it?Juror Ed: Yes. Crazy. I mean, then suddenly ten hours, he disappeared.Murphy: Anybody doubt that it could be done?Juror: I did.Another Juror: Yeah. Juror Wayne: Just the simple fact that there was no evidence—no witness to put him in—Polk county, none of those things. Keeping an open mind, he was still innocent.

Jurors also weighed whether Serrano’s nephew, Alvaro, was a possible suspect as the defense suggested. After all, the nephew had not only rented the car, he also admitted to lying to investigators early on.

Murphy: Do you think he was in on it at all, the nephew?Juror Cheryl: No, I don’t.Murphy: None of you do?Jurors: No.Juror: Nelson Serrano hung him out to dry.

And finally, jurors had to evaluate probably the most important evidence in the case — that fingerprint on a parking lot ticket from the Orlando airport.

Jurors heard two experts say it was Serrano’s... but another opened the door to doubt, conceding under defense questioning, that the print could have been planted.

Juror April: I had my reservation about it It made me second guess it.Murphy: If it’s forged, does the case fall apart? Juror JW: That would be the one that the defense has knocked out of knocked out of the park. Murphy: And here’s this—this very well-credentialed expert telling you, “I don’t know. I’ve got reservations.”Juror JW: Right. And that would have been strong evidence that he was not in Florida.

After seven weeks of trial, Serrano’s very life hung in the balance...the jurors still unsure themselves at the end of testimony, what side they’d come down on.

Murphy: A show of hands question. When the defense sat down, from their closing argument to youhow many of you were right on the line and didn’t know where you were going to vote? Show of hands.Juror JW: I didn’t know.Juror Dennis: That this was innocent until proven guilty still to that moment—

Jurors: (shaking head) yes.

The jury was out. Stretched nerve endings got rawer yet.

Four victims, four families.

They had waited for this moment for nine years. But neither they, nor Serrano’s family would have to wait much longer.

After six hours of deliberations, a verdict. Anticipation outside the courtroom...even Tommy Ray, the cold case cop who pursued Serrano for so long, looked frazzled.

The jurors filed back. The families held hands, braced.

The defendant stood as the judge read the verdict.

Count two, the defendant is guilty.Count three, guilty...Count four, guilty...

Serrano never flinched.

The families’ gasps were silent but the relief was visible.

In the end, jurors say they didn’t buy the defense argument that Serrano couldn’t have had enough time to travel and commit the crime all inside 10 hours.

Juror Wayne: There was plenty of time to do what he wanted to do.

The other thing critical to their conviction: Serrano’s fingerprint.

Juror Sheree: His alibi was shot with that fingerprint on the parking ticket.

Outside the courtroom, it was as thought the families were finally able to have the wake they’d been denied all these years.

The Dossos who lost their son, Frank and daughter, Diane.

Nicolette Dosso: Now he’s going to suffer...what he did to my kids, what he did to my kids, he took everything away from me.

The Patissos who lost their son, George.

and the grieving widow of the partner in the business, George Gonsalves.

And then there was Maria, and her three girls. They lost their father...on, of all days, the twins birthday.

Dennis Murphy, Dateline correspondent: The twins will have their birthday tainted as long as they live.Maria Dosso Jacoby, Frank Dosso's wife: Yeah. They didn’t want to celebrate their birthday on December 3rd anymore. And I told them that was also a beautiful day. It was the day that I started dating their father and it was the day that they were born. And we couldn’t focus on that day as just being the tragic day that it was.

Tommy Ray, the detective who never gave up, put close a chapter of his life, almost a decade pursuing a man who’d boasted in the first hours of the investigation that they’d never catch the one who did it.

Tommy Ray: Look at the families, man...it’s all about them and finally they’re getting some justice after all these years.

Agent Tommy Ray promised the families he’d never retire before this case was over. Now, finally, he could.

The jury has recommended the death penalty for Nelson Serrano. Sentencing is expected some time after the New Year. Prosecutors say the judge is likely to follow the jury’s recommendation.