The launch of a European space telescope called COROT Wednesday could help planet hunting astronomers spot a bevy of small, rocky worlds only a few times larger than Earth.

But the detection of a true, Earth-like world — the holy grail amongst planet seeking astronomers — will have to wait at least another two years until the launch of NASA’s space observatory, Kepler.

In just a little over a decade, the number of known planets outside our solar system has jumped from zero to over 200. But most of these extrasolar planets are so-called “hot-Jupiters,” large, gassy worlds many times bigger than Jupiter which orbit very close to their stars.

Astronomers’ current catalogue of known exoplanets is heavily skewed towards these fast, gaseous worlds because most of the exoplanets discovered to date were spotted using a technique that watches for the slight gravitational pull that orbiting planets can have on their parent stars. Because the planets would have to be large and orbiting close to the star to exert any effect at all, these are the planets that are discovered.

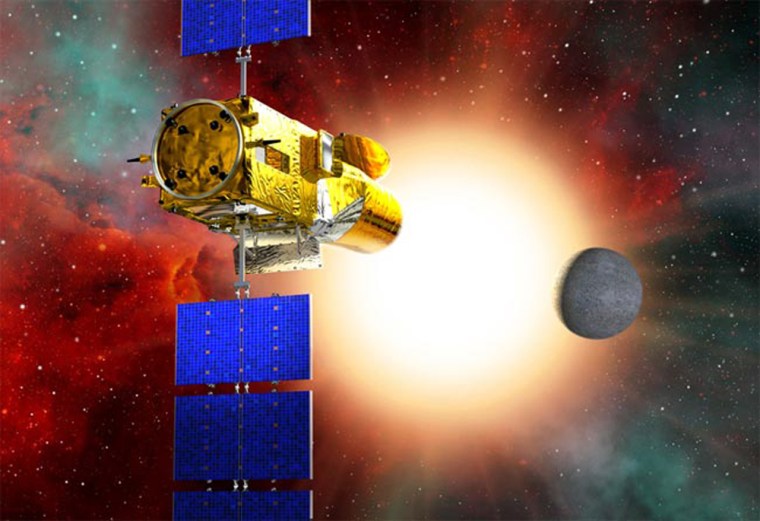

Flying high above the Earth’s atmosphere, the Convection Rotation and planetary Transits satellite will use a different technique better suited to finding smaller worlds. Called the “transit” technique, it will detect extrasolar planets by measuring the dip in starlight their passage creates as they glide across the face of their parent stars.

COROT’s 27 centimeter (10.6 inch) lens will monitor the brightness of the stars, looking for the slight dip in starlight caused by the planet's passage. COROT will be able to monitor hundreds of thousands of stars simultaneously and will turn its unblinking eye toward different parts of the sky for 150 days at a time. COROT is expected to find between 10 to 40 rocky worlds over the course of its two and a half year mission, along with tens of new gas giant planets.

As it’s observing a star for signs of a planet’s passage, COROT will also watch for “starquakes,” acoustical waves generated deep inside stars which ripple across a star’s surface, altering its brightness. This information can be used to calculate a star’s precise mass, age and chemical composition.

In 2008, NASA will launch Kepler, a space telescope that works in the same way as COROT, but which will be able to detect the first Earth-sized planets in similar orbits to our own world.

Slideshow 12 photos

Month in Space: January 2014

“The goal of Kepler is to find Earth-sized planets in habitable zones around equivalent Suns, or slightly smaller,” said Micheal Moore, NASA’s program executive for the mission. “We actually like them a bit smaller than our Sun itself, but basically the same thing.”

Unlike COROT, which will watch multiple targets over the course of its mission, Kepler will continually stare at about 100,000 stars in Cygnus region for four years. Cygnus is a prime viewing spot to look for rocky planets because it is outside the plane of our solar system, so interference from the Sun’s light is not a problem. “If you pick an area where you don’t have to look through the Sun to get there, then you have twenty-four seven, 365 viewing of the sky,” Moore said.

Kepler will also be positioned in an Earth-trailing solar orbit so that its view is not obstructed by Earth or the Moon. In contrast, COROT will be positioned in a low Earth orbit. “Since the COROT guys are going to be in a low Earth orbit, they don’t have the opportunity to be able to stare at one patch of sky for the entire mission of multiple years,” Moore said.

COROT and Kepler are only the first of many planned projects designed to look for planets similar to Earth. ESA is also working on another project that will be capable of chemically analyzing light reflected off a distant planet's atmosphere, possibly revealing signs of life. Called Darwin, the planned satellite will be launched sometime around 2020.

The COROT mission is led by the French national space agency and supported by other international partners, including the European Space Agency Austria Belgium, Germany, Spain and Brazil. The satellite is set to launch into space on Dec. 27