A white former sheriff’s deputy who was once thought to be dead was arrested on federal charges Wednesday in one of the last major unsolved crimes of the civil rights era — the 1964 killings of two black men who were beaten and dumped alive into the Mississippi River.

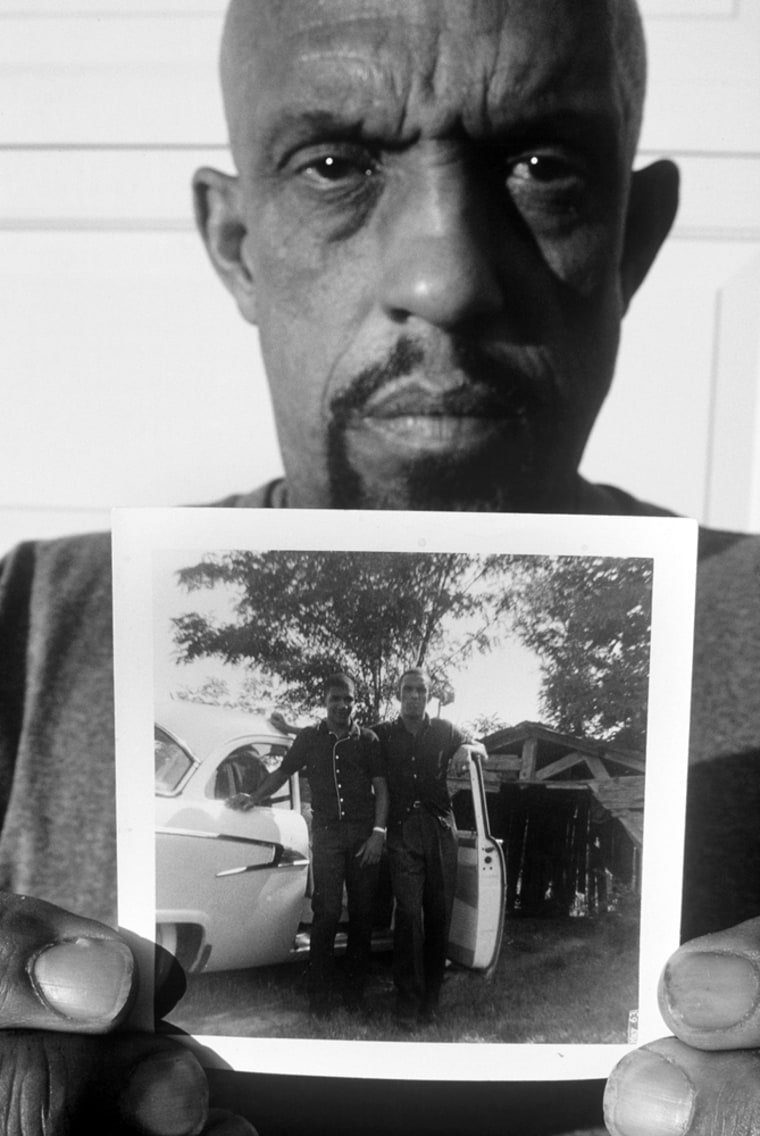

The break in the 43-year-old case was largely the result of the dogged efforts of the older brother of one of the victims, who vowed to bring the killers to justice.

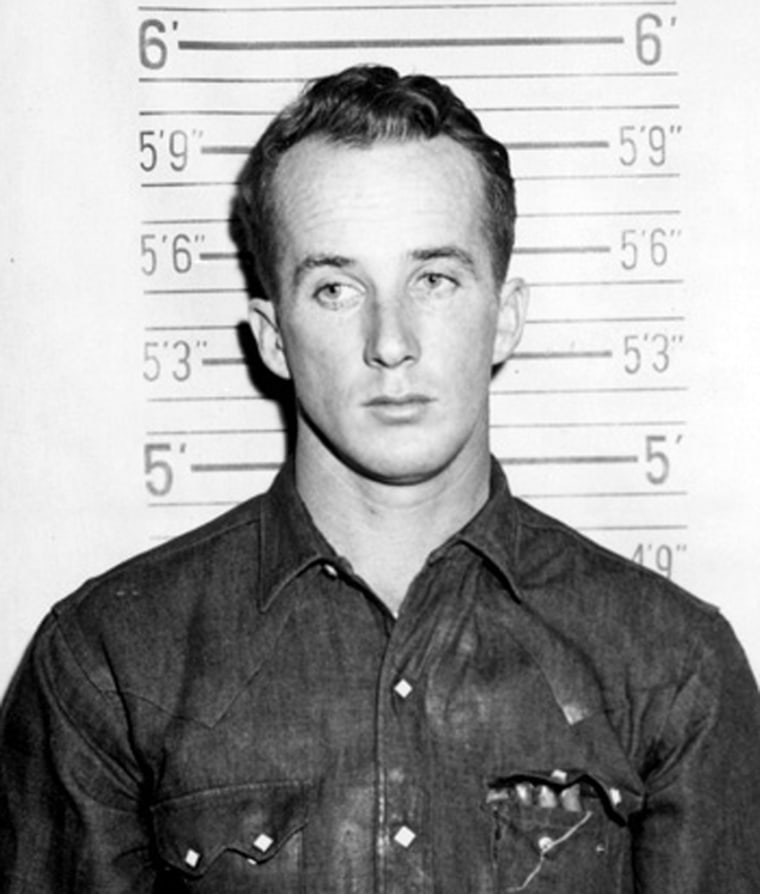

James Ford Seale, a 71-year-old reputed Ku Klux Klansman from the town of Roxie, was charged with kidnapping hitchhikers Charles Eddie Moore and Henry Hezekiah Dee, both 19.

The victims’ weighted, badly decomposed bodies were found by chance two months later in July 1964, during the search for three civil rights workers whose disappearance and deaths in Philadelphia, Miss., got far more attention from the media and the FBI.

Seale is expected to be arraigned on Thursday in Jackson.

A second man long suspected in the attack, church deacon and reputed KKK member Charles Marcus Edwards, now 72, was not charged. There was no immediate explanation from federal prosecutors. Nor did they say why Seale was not charged with murder.

Closing books on the past

The arrest marked the latest attempt by prosecutors in the South to close the books on crimes from the civil rights era that went unpunished. In recent years, authorities in Mississippi and Alabama have won convictions in the 1963 assassination of NAACP activist Medgar Evers; the 1963 Birmingham, Ala., church bombing that killed four black girls; and the 1964 Philadelphia, Miss., slayings.

“I’ve been crying. First time I’ve cried in about 50 years,” Moore’s 63-year-old brother, Thomas, said after the arrest. “It’s not going to bring his life back. But some way or another, I think he would be satisfied.”

Dee’s sister, Thelma Collins, told The Associated Press through grateful sobs: “I never thought I would live to see it, no sir, I never did. I always prayed that justice would be done — somehow, some way.”

Seale and Edwards are suspected of kidnapping the two victims in a Klan crackdown prompted by rumors that Black Muslims were planning an armed “insurrection” in rural Franklin County. Seale and Edwards were arrested at the time.

But, consumed by the search for the three missing civil rights workers, the FBI turned the case over to local authorities. And a justice of the peace promptly threw out all charges against Seale and Edwards.

In 2000, the Justice Department’s civil rights unit reopened the case.

Back from the dead

For years, Seale’s family had told reporters that he had died. But in 2005, Thomas Moore and a Canadian documentary filmmaker, David Ridgen, found Seale, old and sick, living just a few miles down the road from where the kidnappings took place.

“If they hadn’t brought it to my attention, I wouldn’t have known to do anything,” said U.S. Attorney Dunn Lampton, chief federal prosecutor in Jackson.

For a brother, a burden

Thomas Moore said he always carried a burden of guilt over his younger brother’s death.

“I walked around with an amount of shame,” the Colorado Springs, Colo., man said. “I didn’t know why, why it happened to us, that I wasn’t there to do something — to do SOMETHING.”

Former Gov. William Winter, who was co-chairman of President Clinton’s racial reconciliation initiative, said the latest arrest — though done by federal rather than state authorities — shows that Mississippi “now is obviously seeking to make up for lost time in bringing people to justice.”

“Mississippi is taking a look at those crimes that were committed in a different era when a different attitude prevailed,” said Winter, who was governor in the 1980s.

Anatomy of two murders

On May 2, 1964, Charles Moore and Dee were hitchhiking near an ice cream stand in the town of Meadville when Seale pulled over and offered them a ride, a Klan informant told the FBI. The Klan had heard rumors of Black Muslim gunrunning in the area, and Seale believed the two were involved, authorities said.

According to FBI interrogators, Edwards admitted that he and Seale took the two men into the woods for a whipping. But Edwards said both men were alive when he left them.

An informant told the FBI that Seale’s brother and another Klansman took the unconscious blacks to the river, lashed their bodies to a Jeep engine block and some old railroad tracks, and dumped them over the side of a boat. The other Klansmen and the informant have since died.

Federal authorities turned the Dee and Moore case over to local authorities. A short time later, a justice of the peace called an end to the inquiry without presenting evidence to a grand jury.

Feds focused on another case

Searchers were combing the woods and swamps for James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner when the remains of Dee and Moore were discovered near Tallulah, La. The bodies of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner were found in an earthen dam in Mississippi a short time later. They were the victims in the more famous case.

According to FBI documents from the 1960s, authorities confronted Seale and told him they knew he and others killed the hitchhikers, and “the Lord above knows you did it.”

“Yes,” Seale was quoted as replying, “but I’m not going to admit it. You are going to have to prove it.”

The Justice Department reopened the case after The Clarion-Ledger of Jackson uncovered documents indicating that the beatings had occurred in the Homochitto National Forest, giving the FBI jurisdiction. But the case languished until Seale was located.

“I had other plans to confront him a long time ago — violently,” Thomas Moore said.