Right off the bat, Dr. Anita H. Clayton wants to make it clear that “this is not about men.”

Well it is a little, at least for heterosexual women, but Clayton exaggerates in the interest of reassuring me. She has a theory that many women are dissatisfied with their sex lives and I’m expecting the usual indictment of insensitive male fumbling, with the words “beer,” “ba-da-bing,” “foreplay,” “seventh-inning stretch” and “torn sweatpants” figuring prominently.

Instead, she says, "We women need to examine ourselves and the types of sexual beings we are.”

Hmmm. Interesting.

It also raises a question I’ve been wondering about for some time now. Clayton, president of the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) and a psychiatrist with the University of Virginia Health System, has a new book, "Satisfaction: Women, Sex, and the Quest for Intimacy," with writer Robin Cantor-Cooke. In it Clayton argues that too often women unwittingly sabotage their own sex lives. She also gives some possible explanations and solutions. The book joins a rapidly expanding list of such books, and lots of discussions at meetings like those held by ISSWSH and other organizations about women and sex and satisfaction.

Yet it has been 34 years since Erica Jong’s "Fear of Flying"and 30 years since Shere Hite’s "Hite Report"on female sexuality. Women and desire and how to have good sex have been floating around pop culture for decades. At first glance, these issues would hardly seem to be the secrets Clayton says they are. So why this boom in women’s how-to sexual info?

Partly, suggests sex guru Lou Paget, it’s because science has marched on. Paget, based in Los Angeles, writes books of her own, like "Hot Mommas: The Ultimate Guide to Staying Sexy Throughout Your Pregnancy and the Months Beyond," and gives sex seminars to groups of women. They ask her, for example, what happens when women have babies. “Your estrogen plummets, your prolactin shoots up, and you get a surge of oxytocin to help you bond with the baby, not your lover.” All that kills desire.

Today, there are explanations for lack of female sexual desire. "It’s not, ‘Well, I’m strange,'" Paget says. "People want to figure things out. Being in therapy is normal now. Ten or 15 years ago it wasn’t as common. Women say, ‘I have something and I want to deal with it.’”

Men have an advantage because we exist in a binary 1 and 0 world when it comes to sex. If we’re worked up, it shows. If we’re not, it doesn't. We’re also, from a very early age, penis autodidacts, geniuses who know what makes the things work and what runs around inside our brains when they do. And now, if they’re not working, we head to the doctor’s office for a pill.

As good as it gets?

Women on the other hand, are often stumped. “I see couples in their 30s, many of whom have had sex with only few other partners, and the women know very little about their own responses and capacity for pleasure,” reports New York sex therapist Joy Davidson, author of "Fearless Sex." It’s not so much that they are completely dissatisfied, she says, but that they are only “marginally satisfied.”

“They are experiencing very little in the way of satisfaction because they don’t even know what level to reach for,” says Davidson.

This is one of Clayton’s main arguments. When sex researchers try to study female sexual response, or to treat female sexual dysfunction, she says, subjects “don’t even know their own baseline functioning, even lubrication. They don’t know. You have to be taught what to look for, and we don’t teach this. We don’t tell women about sex very much and [response] is all internal,” so women can’t see it.

But the problem isn’t just physical. Women find themselves frustrated by media, Clayton says. (If it isn’t men’s fault, you can count on it having something to do with the media.)

In our celebrity-obsessed culture, in which beauty and an overt sexiness is prized above, oh, talent, many women assume that celeb babes get to live on some higher plane of sexual existence that is closed to other women. Sex in entertainment culture is often portrayed as extraordinary, explosive, exciting. So women come to expect this from their own lives, setting themselves up for disappointment.

Davidson places less blame on media. The romance and sex in movies and on TV are, as part of entertainment, “peak experiences.” Everybody can have very similar peak experiences, she argues. Either way, peak experiences or frustrating fantasy, the market for advice on having better sex gets stoked.

Whatever the source of dissatisfaction, women are too often reluctant to talk about sex with other women, with their lovers, even their doctors. “We are afraid to speak up,” Davidson says, “and so we stay in patterns.”

“If men have a bad experience, it’s a crisis,” Clayton says, referring to a bout of impotence. “They run to the doctor. Women do not.”

Paget has another take. Men can run to the doctor because they have new drugs, but they didn’t used to go either. Mike Ditka and Bob Dole and that really cute woman wearing her man’s dress shirt (and calling him “my man”) made it OK.

She argues that younger women, say women under 30, aren’t really that reluctant to talk sex, partly because of the foundation laid by their feminist forebears and partly because of the “medicalization” of women’s sexuality, which has made the topic a health issue, not a moral one, just like male impotence.

Still, many women either won’t talk about dissatisfaction or don’t know what level of satisfaction is possible. They wind up receptive to what comes their way in a sexual relationship, rather than, in Davidson’s words “going in with your own agenda, your own self determination. Women need to focus on our own erotic life. We need to value and cherish our sexuality and eroticism and then invite partners to partake of what we have already discovered.”

'The laundry can wait'

Most of the books out there are primers on how to do just that and most suggest, as Clayton does, that women “self-stimulate" (for those of you not in the sexology profession, that's masturbation). The goal, Clayton says, is to learn about your body and how it reacts, and a little about your mind, too. What are you thinking about? Do you like it fast, slow, hard, soft?

Second, speak up. Speak up to your doctor if necessary, but be absolutely sure to speak up to your lover.

“Guys are not saying, ‘Do not tell me. I don’t want to know,’” Clayton says. “Women are the ones keeping these secrets.”

“Women are more careful not to say something that could be injurious to a partner’s feelings or ego,” says Paget.

But it’s not just asking a man for more or different. Women should ask themselves hard questions about their sexual lives and what they can change, regardless of how great a lover a man is.

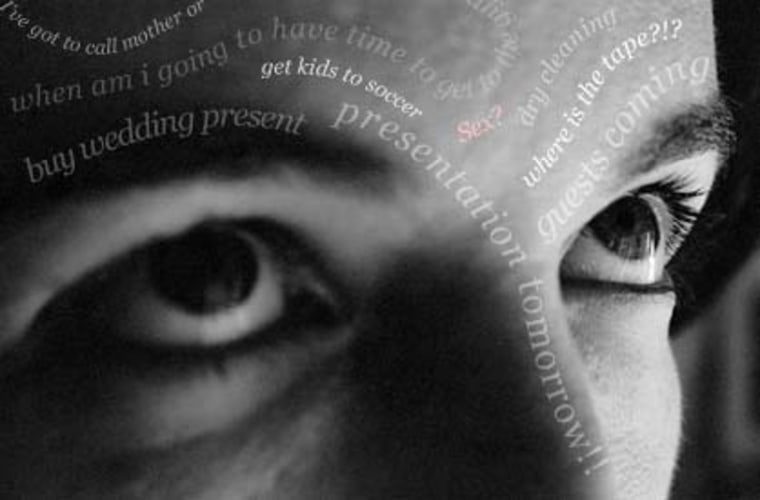

Far too many women fail to define themselves sexually. “We define ourselves as workers, wives, mothers, daughters. We prioritize those things, and then we put sex low on the list. No guy does this to us. We do it to ourselves.”

Men place it right up there with, say, breathing. “A bomb could go off in the house and if a guy is having sex, he can go on having sex,” Clayton says. “A woman can hear a pin drop and think something’s wrong” and stop immediately.

Yet, if the slew of new books and hours of seminars and advice are at all true, women can find sexual happiness.

“We can change,” Clayton believes. “We can tell ourselves that the laundry can wait. Let’s go have sex.”

Brian Alexander, a California-based freelance writer and contributing editor for Glamour magazine, is working on a new book about sex for Harmony, an imprint of Crown Publishing.