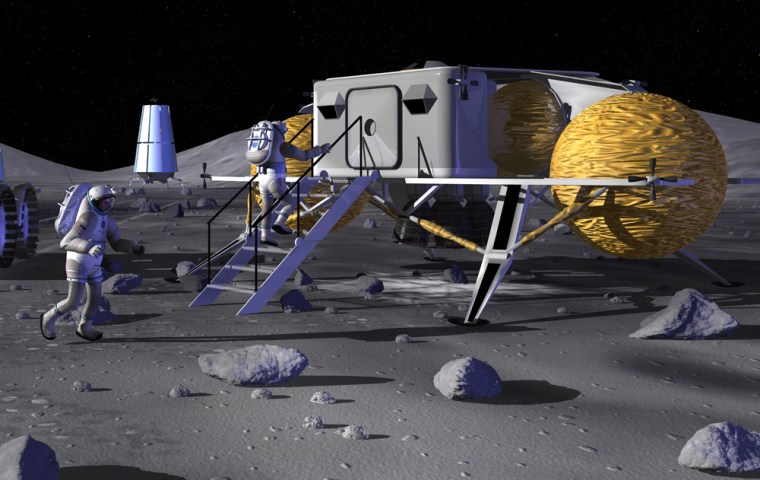

Imagine a world where microwave-beaming rovers cook dust into concrete landing pads ... where your living quarters are dropped onto the land from above, then inflated like an inner tube ... where the grit is so abrasive that even the robots have to wear protective coveralls.

It may sound like science fiction, but these are actually some of the ideas being floated as part of NASA's plan to build a permanent moon base starting in 2010. To follow through on those sky-high ideas, the space agency is turning to some down-to-earth experts, ranging from polar researchers to miners and earth-movers.

"We will be looking outside the agency quite a bit as well as inside the agency," said Larry Toups, habitation systems lead for NASA's Constellation Program Office. "We have a lot of folks here who are very innovative and understand the space environment quite a bit, but you do have a lot of expertise outside NASA as well, and we intend to involve those folks."

Those folks include the twin giants of America's space industry, The Boeing Co. and Lockheed Martin. But some less conventional players are involved as well:

- Illinois-based Caterpillar and allied companies have been advising NASA on the dynamics of dirt and the challenges of moving heavy equipment over the lunar surface.

- Canada-based Norcat and Electric Vehicle Controllers are working together to develop a drill suitable for mining on the moon. Norcat is traditionally better-known for its industrial safety training programs, but this June the company is sponsoring a planetary mining conference, with the moon in its sights.

- Delaware-based ILC Dover, which manufactures components for NASA's spacewalk suits as well as the airbags used by NASA's Mars rovers, is branching out to develop inflatable prototypes for lunar habitats. Nevada-based Bigelow Aerospace may offer its own inflatable modules for future moon outposts.

- The National Science Foundation is working with NASA and ILC Dover to build and deploy an inflatable test habitat in Antarctica later this year.

NASA announced the broad outlines of its plan for an eventual lunar outpost less than two months ago. The general idea is to set up shop on the rim of a crater near one of the moon's poles. Such areas would be in sunlight, with a line-of-sight link to Earth all year round. The first crews would stay for just a week at a time, but by 2025, six-month tours of duty would be the norm.

The polar outpost would serve as NASA's base for lunar research and a test bed for Mars exploration. Some have even grander plans, envisioning the moon as an eventual platform for luxury hotels, astronomical observatories and helium-3 mining operations. The idea of a permanent platform is what distinguishes the future effort from NASA's previous moon program, said Dallas Bienhoff, manager for in-space and surface systems at Boeing Space Exploration.

"Just getting there and getting home was a big deal for Apollo," he told MSNBC.com. "We know we can do that, even though we haven't done it in 30-plus years. What we want to do is prepare the beachhead for people other than NASA. Basically, the intent is to lay down the foundation for a permanent presence on the moon by whoever wants to be there."

NASA spokesman Kelly Humphries cautioned that, for now, the space agency is focusing on the spacecraft required for moon trips rather than on lunar habitats. "Those don't do you a whole lot of good if you don't have a way to get to the moon," he told MSNBC.com. Nevertheless, NASA and its corporate partners are already building prototypes to test some of the more unorthodox ideas — like those inflatable habitats, for example.

‘Honey, I Shrunk the Space Station’

Why inflatable habitats? Bienhoff explained that the metal-hulled modules used on the international space station couldn't make it to the moon because they're too heavy.

The typical space station module weighs 30,000 pounds — but NASA's moonships, as currently planned, would have a maximum payload capacity of only 13,000 pounds.

Inflatable modules could get around that limitation. Dave Cadogan, research director at ILC Dover, said the modules would be compressed to fit a smaller space on NASA's smaller spaceships, dropped off on the moon, and only then filled with air, equipment and all the comforts of a lunar home.

Bigelow Aerospace already has lofted one inflatable test module into orbit and is gearing up to launch another one in April. Last year the company's billionaire founder, Robert Bigelow, told reporters that "we definitely have lunar architecture in mind."

ILC Dover, meanwhile, has built one inflatable prototype for NASA's Langley Research Center, and it's in the midst of designing another for the NASA-NSF test in Antarctica. NASA's Toups said the new prototype would be shipped in compressed form to the South Pole this fall and inflated to full size for use by polar researchers — as, say, a dive shack or a meeting place.

"We'll have monitors and sensors built into it so we'll be able to track how it does with sustained use," he said.

Antarctica and other extreme environments on Earth — such as the Canadian Arctic, the Arizona desert and the underwater Aquarius habitat — are becoming key proving grounds as NASA and its partners develop their exploration technologies.

"What I see the Antarctic experience doing is actually being an analog for what we might do on the moon, and then once we get to the moon, keep in mind that we'll be using that as an analog for the operations that might be required for Mars," Toups said.

More alien than Antarctica

But there are some lunar challenges that go far beyond what Antarctic researchers have to deal with.

For example, radiation exposure poses much more of a risk on the moon than it is beneath Earth's warm blanket of atmosphere. Habitats on the moon might have to be covered by heaped-up lunar soil, also known as regolith. Other shielding materials could include tanks of water, or strategically placed hardware, or extra layers of reinforced polyethylene.

Then there's the dust: During the Apollo missions, abrasive moondust worked its way into every nook and cranny — even the joints on the astronauts' spacesuits. "After three days on the lunar surface, they had work through the metallic protection on their gloves, because of the abrasion," Bienhoff said.

If too much dust gets inside the lunar habitat, it could pose the kinds of health problems suffered by miners and asbestos workers in the past. To keep the dust down, astronauts might have to wear disposable coveralls during surface operations, Cadogan said — and lunar robots might need coveralls as well to protect their mechanical joints and bearings.

Living off the dirt

Moon dirt isn't all bad, however. If you know how to treat it right, it can serve as a building material as well as a source for vital supplies — and that's where companies such as Caterpillar enter the picture.

"When you're moving large pieces of equipment, using whatever types of devices you are using, how is the soil going to react?" NASA's Humphries said. "How is it going to compact underneath the wheels? Could it potentially get in the way and ball things up? What is its usefulness in terms of being bulldozed around to help make barriers to radiation, or even to flatten out the surface for ease of maneuvering things in an outpost-type area? They're looking at a lot of different things in that regard — in particular in the area of robotics, because they're anticipating that robotics will be a key component there."

Construction and mining companies have been advising the more traditional aerospace companies on all those issues, said Larry Clark, senior manager for Lockheed Martin's spacecraft technology development laboratory. It turns out that a heavy-duty Caterpillar tractor probably wouldn't be suitable for the moon, he said.

"We can't afford to launch a large vehicle like that, so we've got to make things smaller and lightweight, but just as efficient mechanically," he told MSNBC.com.

Pint-size robo-tractors could be used to build up protective berms around lunar facilities, or dig up loads of moon soil for industrial-scale extraction of water and oxygen. Researchers have already started to map areas where frozen water may lurk — perhaps in the depths of permanently shadowed craters near the poles. And if the water is broken down into hydrogen and oxygen, that could provide rocket propellants as well as air for breathing.

In addition to potential traces of frozen water, lunar soil contains oxygen-rich minerals.

"It doesn't take a lot of soil to make the oxygen we need," Clark said. The way he figures it, processing the top 2 inches (5 centimeters) of soil from an area half the size of a basketball court could yield enough oxygen to keep four astronauts alive for 75 days.

Moon dirt in the microwave

Another neat trick involves cooking the lunar soil right on the surface to turn it into a concrete-hard crust. "You take a microwave and heat the soil up, and it actually fuses into a solid," said John Stevens, Lockheed Martin's director of business development for human spaceflight.

Larry Taylor, a University of Tennessee planetary scientist, has proposed building "lunar lawnmowers" that could go back and forth to create hardened launch pads, roads and even radio telescope dishes.

Over the long haul, such technologies could turn the moon into much more than a way station on the road to Mars, said Bob Davis, director of business development for space exploration at Northrop Grumman.

"We're learning what the moon has to offer as not just an outpost, but as a location where we might derive economic benefit," he told MSNBC.com. "Who knows?"