Julie Roehm got a call from her boss's assistant at 12:15 p.m. on Dec. 4. J. John Fleming, then chief of Wal-Mart Stores Inc.'s marketing department, wanted a word with his senior vice-president. Walking to Fleming's office at the Bentonville, Ark. headquarters, Roehm recalls thinking she was about to be fired. She was right. Ten months after being recruited to help modernize Wal-Mart's tired brand, Roehm was out.

The meeting lasted seven minutes, Roehm says. A "very nice" human resources manager collected her company badge, Palm Treo, corporate credit card, and, yes, Wal-Mart discount card. Then the HR representative escorted Roehm out a side door to the parking lot. Standing there in the sunshine, she recalls asking herself: "How do I feel about all this?' I sort of felt relieved."

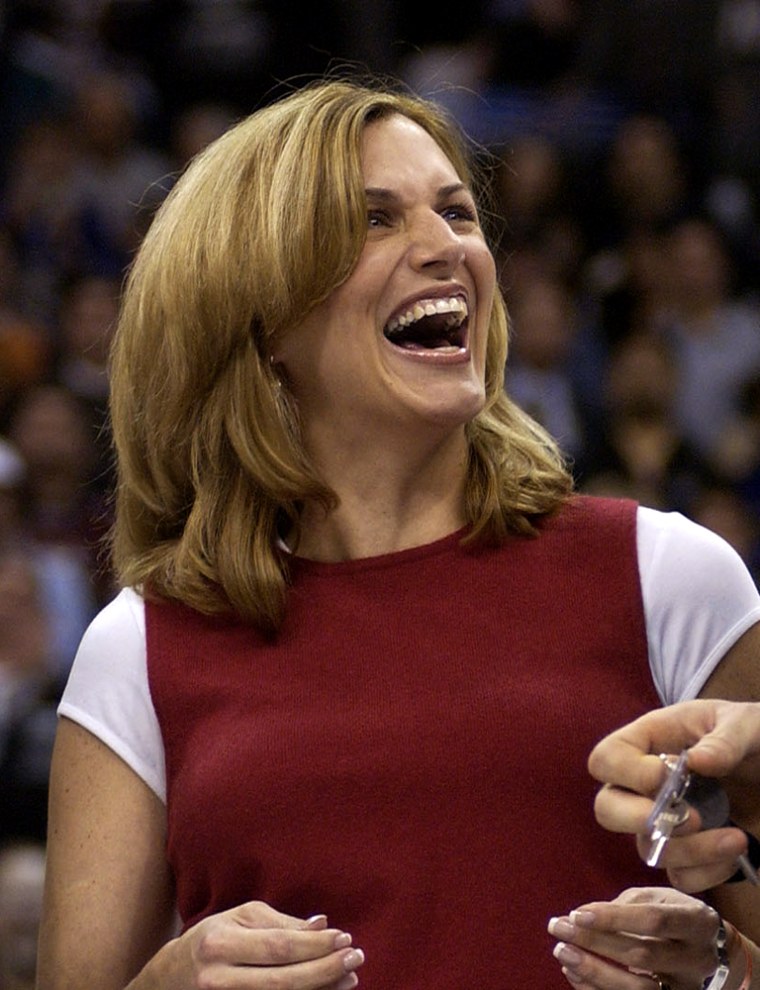

It isn't often that the dismissal of a midlevel executive makes national news. But Julie Roehm is no ordinary executive. Before joining Wal-Mart, Roehm, 36, earned an edgy reputation as director of marketing communications at Chrysler Group. There she famously agreed to sponsor an alternative half-time Super Bowl show. It was jokingly called the Lingerie Bowl and featured scantily clad models. After protests, Chrysler backed away. Given her colorful career, Roehm's hiring by one of America's most colorless companies always struck friends and industry insiders as odd. And few were surprised when Roehm and Wal-Mart parted ways.

But the dismissal ignited controversy. For several weeks, press reports circulated that Roehm was fired for accepting gifts and gratuities from ad agencies she was doing business with and because she carried on a personal relationship with a subordinate. Roehm and the man in question, Sean Womack, who was fired shortly after she was, deny both allegations. Now, for the first time, Wal-Mart says it has "irrefutable evidence that the relationship involved specific instances of inappropriate personal conduct." What's more, spokesperson Mona Williams told BusinessWeek: "Wal-Mart is prepared to prove that this misconduct did in fact occur."

Warring fiefdoms?

On Dec. 15, Roehm filed suit against her former employer, alleging breach of contract, fraud, and misrepresentation. Roehm seeks payment of more than $1.5 million, to cover severance pay, stock options, restricted stock, and bonus. But in its response to Roehm's suit, the company argues that under the employment contract, it is not liable for such payments if the plaintiff is "terminated as the result of a violation of Wal-Mart policy."

Now, in her first lengthy interview since filing suit, Roehm gives BusinessWeek her side of the story. As Roehm tells it, hers is a cautionary tale of what happens when a self-described change agent goes to work for a company that needs to reinvent itself but can't. In Wal-Mart's case, she says, the concept of "Everyday Low Prices" was so deeply embedded that the retailer's ambition of getting upscale shoppers to buy more was a nonstarter. Roehm acknowledges mistakes, among them moving too quickly and not adapting to her new workplace. But she also paints a picture of warring fiefdoms and a passive-aggressive culture that was hostile to outsiders. Wal-Mart, she says "would rather have had a painkiller [than] taken the vitamin of change." What has she learned? "The importance of culture. It can't be underestimated."

When Wal-Mart came knocking, Roehm had been working at Chrysler for nearly five years. It was a company that all sides agree fit her temperament perfectly. "We're probably the edgiest automaker in terms of the things we try. And the times Julie went over the edge have been well documented," says Jason Vines, the automaker's chief spokesman. "But we realized you don't know where the edge is unless you are willing to go over it once in a while."

Roehm was flattered when headhunter Spencer Stuart contacted her in September of 2005 about possibly joining Wal-Mart. She saw an opportunity to head a marketing communications department and be part of a potentially exciting effort to transform the company and its image. By then Wal-Mart was struggling. Earnings growth had stumbled the previous year on continued weak sales growth, and the stock price remained below its 1999 levels. For the first time, a company that for decades had religiously followed Sam Walton's low-price edict suddenly seemed ready to take a different tack.

Roehm and her husband, Michael, who looks after their two boys, age 5 and 8, wondered about moving from suburban Detroit to Bentonville. The pace was going to be a lot slower in Arkansas. In the end, opportunity nixed the negatives. Wal-Mart was promising to continue paying the mortgage on the Detroit home until she sold it, and Roehm's compensation wasn't half bad: A base salary of $325,000, a signing bonus of $250,000, plus restricted stock of about $300,000, stock options valued at approximately $500,000, and an annual performance bonus of up to $400,000.

Still, Roehm recalls friends looking at her "like I was crazy" for taking the job. And from the moment she arrived at Wal-Mart on Feb. 6, 2006, Roehm recognized that fitting in would be harder than she had imagined. This wasn't Chrysler. And the Wal-Mart headquarters, with its windowless offices and gray walls, was hardly inspiring for a woman unafraid of a little color. One of the first things Roehm did was paint her office chartreuse with chocolate-brown trim. That may have been her first mistake—and it's revealing that Wal-Mart, in its response to Roehm's suit, says she is free to collect "a step ladder and paint supplies" left behind after she was dismissed.

Some new hires would keep a low profile and spend their first 100 days listening. That's not Roehm's style. "I get overly excited," she acknowledges. "I wanted to hit the ground running. Go, go, go." No one told her to back off; that's not the Wal-Mart way. Even though everyone was "super nice" and said things like "thanks for participating," Roehm heard from her own staff that "you shouldn't be doing" things like planning skits for the annual meeting.

But Roehm says Fleming, who was not made available to comment, seemed dedicated to doing whatever it took to update Wal-Mart's image. And that included turning the marketing department into a real power center, after years of deferring to merchandising, which had always determined what went on store shelves. "He called us a startup in the world's largest turnaround,'" Roehm recalls.

Fleming had already brought in outsiders to effect change, including five marketing people from PepsiCo Inc.'s Frito-Lay division. They were known as the Frito Five. One was Stephen Quinn, who was charged with building a consumer research and marketing strategy department and reported directly to Fleming. His job was to identify key consumer trends that would help guide the merchants and help determine how the retailer should position itself.

Roehm was Quinn's counterpart. As chief of marketing communications, she was in charge of consumer advertising. And, most important of all, Roehm was to recruit a new ad agency.

Roehm says there was trouble from the start. She says Quinn, who was not available for comment, wouldn't invite her to strategy meetings or return her phone calls. This made it harder to refine her marketing message, Roehm says, adding: "I thought we'd work smarter thinking as a team." Fleming, she says, told her to build bridges with Quinn. But Roehm says she believes that the real problem was that Fleming hadn't clearly defined their roles. She felt her role was being minimized to merely handing off Quinn's market research to the ad agencies. Spokesperson Williams says Roehm's "statements about her working relationship with John Fleming and Stephen Quinn are false." By her third month on the job, Roehm had the sense that Fleming was not going to intervene on her behalf.

Still, she was too busy to fret. For much of the summer, Roehm jetted around the country visiting the 30 or so ad agencies that were bidding to win the $580 million Wal-Mart account. It was during these weeks and months of nonstop travel that Roehm, looking back, realizes she could have played her politics more astutely. Every Friday morning, Chief Executive Lee Scott gathers together 300 managers and executives for an all-purpose meeting in an auditorium at Wal-Mart's headquarters. Roehm, on the road and unaware of how important it was to attend these meetings, missed several in a row. "Had I known," Roehm says, "I never would have been gone on Friday."

Back in Bentonville, the merchandisers were thwarting marketing's efforts to appeal more to upscale shoppers. According to Roehm, the merchants didn't want to take cues on consumer trends from Quinn's team. Roehm says this became abundantly apparent during the back-to-school season when Quinn's people tried and failed to get the merchandisers to push denim, one of the hottest trends in apparel, in the stores. And even as Fleming pushed to upgrade and unclutter store interiors, the merchants pushed for more in-store signage to telegraph that Wal-Mart was still all about low prices.

‘Hooker’ signs

By the end of summer, the merchants were winning the war. As Wal-Mart's same-store sales continued to slide, Roehm says, Wal-Mart decided to refocus on low prices. More price signs began appearing in stores, and price again became the dominant theme in advertising. "I spent so much time on signs in the stores, it was mind-boggling," Roehm says. She recalls a sign for Metro7, one of Wal-Mart's snazzier women's brands. It showed a woman in a black dress walking down a dark street and blared: "Wow Now Pricing." "It looked like she was for sale," says Roehm. "She looked like a hooker."

As fall approached, the deadline for the agency review was looming. On Oct. 15, Wal-Mart finally settled on one of Roehm's top picks, DraftFCB. At the time, both Roehm and agency chief Howard Draft were unaware that someone at his firm had placed an advertisement in an industry publication, celebrating the clinching of several awards. The ad featured a lion mounting its mate with the tag line: "It's good to be on top." Not surprisingly, the ad did not go over well inside Wal-Mart. Roehm thought: "Oh my God. This is the last thing we need." (Wal-Mart would ditch the agency three days after firing Roehm.)

Even small triumphs were turning to ashes. Roehm had helped conceive a TV ad for the Christmas shopping season. It featured a middle-age couple opening presents. The woman, sitting on the husband's lap, opens a box to reveal a red silk nightgown. With his teenage kids and in-laws looking on, the man grins happily. His wife loves the gown. And Wal-Mart, says Roehm, loved the ad. At first, anyway. Then, she says, the company got word of a complaint from a consumer who saw the ad while watching Desperate Housewives; shortly after, the ad was pulled. Roehm couldn't believe it. "With a company as big as that," she says, "you are never going to satisfy 100% of the people."

The beginning of the end arrived on Nov. 30. Roehm was in Chicago for meetings with Draft. While at the agency, she received a message that Eduardo Castro-Wright, Wal-Mart's U.S. president, was dispatching a corporate jet to pick her up. "Eduardo wanted to meet with me," she says. "That's all the message said."

An ice storm was raging in Bentonville when she landed early that evening, shutting down most of the city. She drove to the Wal-Mart headquarters and met Fleming and Castro-Wright in the latter's office. Roehm says they began grilling her about the agency review process, how Draft had been chosen, and who inside the company had voted for it. Roehm says she detected no agenda or sense that they were questioning her judgment.

But when the meeting ended 45 minutes later, she was ushered into another room with an internal security person and someone from legal. They asked if she was having an affair with her subordinate but drilled down most on questions of accepting gratuities and gifts during the agency review process. "It was surreal," Roehm recalls. "It was like good cop, bad cop. They were asking crazy questions and I was thinking, What is this?' I had never been through anything like that before." Four days later, Julie Roehm's Wal-Mart career was over.