The CDC didn't ask for the job of investigating firefighter fatalities. That job was handed to it, after a union boss got a seat next to President Clinton on Air Force One. They were talking blue windbreakers.

After a plane or train crash, the National Transportation Safety Board dispatches its experts within two hours. The investigators in their familiar jackets take charge of the scene, secure evidence, follow leads.

The NTSB calls it the "Go Team."

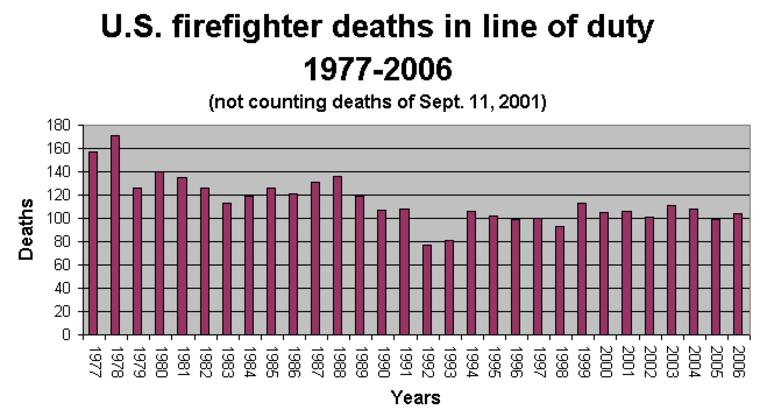

That's what Harold A. Schaitberger had in mind. Now the general president of the International Association of Fire Fighters, he got an hour in the air with Clinton in the mid-1990s. The union boss told the president how the number of firefighting deaths, which had been declining sharply, was stalled at about 100 a year.

It might not have hurt their case that the firefighters had endorsed Clinton in 1992 and 1996. The president put $2.5 million in his budget for fiscal 1998 to study firefighter deaths. Congress gave the job to the Centers for Disease Control.

"We wanted to model it after the NTSB process," said Richard M. Duffy, the union's health and safety chief. "The public expects it. They expect to see those blue windbreakers every time there is such an incident.... And I think we’re getting to the point that firefighters expect that, too.”

After a decade and more than 300 investigations, how is the CDC doing?

Call it the "No Go Team."

An investigation by msnbc.com shows that the CDC routinely takes as long as a month — and sometimes as long as nine months — to visit the scene of firefighter deaths. The CDC also:

- Doesn't investigate a death at all if the fire department or fire union raises an objection.

- Has cut back in the past three years on the number of investigations.

- Destroys information that could help identify patterns of hazards with firefighting equipment, training and tactics.

"Frankly I think the American firefighter deserves better," said Eric Schmidt, a former fire captain who was the CDC's first and only fire protection engineer before he was fired in 2000.

Msnbc.com reported Monday how documents show that Schmidt's managers in the CDC’s firefighter fatality program squelched his attempt to investigate PASS devices, the "man down alarms" that are intended to help comrades rescue an injured or immobilized firefighter. Schmidt had noticed that, in two fires in which firefighters died, the alarms weren't heard. When he kept investigating equipment problems, he was fired. Before the CDC issued a warning and recommended that the standards for PASS alarms be raised in 2005, 15 firefighters died in fires and their PASS alarm either didn't sound or wasn't loud enough to be heard, so rescuers had less chance to find them quickly.

Today, we look more broadly at the quality of CDC's investigations of firefighter deaths.

Equipment so good, it’s dangerous

Firefighting has gotten deadlier over the past decade, and one of the surprising reasons may be improved protective equipment.

With better gear, firefighters no longer surround and drown a fire — they go in. Instead of rubber coats, they have fire-resistant Kevlar. A generation ago, firefighters felt the heat and knew it was time to back out. Now, by the time they feel the heat, it may be too late to leave.

"Better protective equipment was never intended for people to get in deeper or stay in longer," said Bruce Teele, the National Fire Protection Association’s leading expert on firefighter equipment.

"Try telling that to a firefighter," countered Duffy, the union official.

Firefighters go where they're needed, sometimes ignoring the dangers even when no one is inside a burning building to be saved.

About 100 firefighters each year die on the job in the U.S. The number had been declining until the early 1990s, when it flattened out. It has stayed at 100 (not counting the 343 firefighters who died on Sept. 11, 2001), which means that the death rate per fire has climbed sharply, because fire safety efforts and smoke detectors have substantially reduced the number of fires. The number of structure fires fell by about one-eighth just in the past decade.

Last year was typical, with 104 firefighters dying in the line of duty, according to the memorial list kept by the U.S. Fire Administration.

The lack of progress in reducing fatalities is why Congress gave money to the CDC in 1998 to study firefighter deaths and make recommendations on how to avoid them. The CDC's occupational safety division was chosen because it had the experience and authority to investigate in workplaces.

Heart attacks on the job and vehicle accidents on the way to the fires account for about half of the firefighter deaths. The other half occur while fighting fires.

Why deaths per fire are increasing

Why are those deaths increasing? Studies have identified several reasons:

- Modern synthetic fabrics and furniture burn hotter than older furnishings. Americans have more electronic gear and other possessions in their homes, additional fuel for a fire.

- Lightweight wooden trusses in modern roofs collapse more easily than older beams, trapping more firefighters.

- Fire crews have been reduced and fire stations closed to hold down local tax bills. That means response times are up, and fires are burning longer before fewer firefighters arrive to attack them.

- A final irony: With fewer fires, there's less practice for firefighters and fire chiefs, so bad decisions may be more likely.

Before the CDC got involved, only a small number of fatalities were investigated, first by the National Fire Protection Association, and then by the U.S. Fire Administration. The Fire Administration reports were more thoroughly documented than the reports now done by CDC; they included timelines; dispatch communications; a description of the firefighters' protective equipment; and a description of changes made by the fire department after the fatalities. And they were more frank in describing errors in judgment by firefighters and incident commanders. Sometimes those investigative reports angered the fire union; sometimes they angered the fire departments; sometimes both.

When the CDC got the task, it assigned it to a small group in the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, or NIOSH, in Morgantown, W.Va., which had previously been investigating farm accidents, construction accidents — even deaths by industrial robots. Now it added the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program.

The firefighter fatality program isn’t a regulatory program — it doesn't enforce federal safety standards like OSHA does. Instead, it is supposed to make recommendations based on good science.

Msnbc.com found that the CDC delays sending investigators to the scene of firefighter fatalities. Although its investigation manual calls for a site visit within three weeks, the typical or median delay is actually 33 days, according to investigative reports studied by msnbc.com. The longest delay was 266 days, or just about nine months.

The program does not have a 24-hour telephone line so that it can be notified of fatalities. "We do have a voice mail," said program manager Dawn Castillo. "If the call comes in on the weekends, we check it on Monday."

A month or more after a fatal fire, witness recollections are no longer fresh. It's often too late to secure the evidence or take measurements at the fire scene. So the CDC's investigators are left to work largely with secondhand information gathered by the fire department, the union, the state fire marshal.

In St. Louis, after two firefighters died on May 3, 2002, the CDC team traveled from Morgantown on June 24, a delay of 52 days.

"The building had already been torn down" by that time, said Laura Morrison, whose husband, Rob, was one of two firefighters who died that night. Other firefighters who were hunting for him said they never heard Rob Morrison’s PASS alarm.

"When they came to investigate, I was really excited about that," Laura Morrison said, because it was "the federal government and they were going to give me the answers I needed. And this was like 40 days later after the fire.

"But I thought they would really investigate, talk to firemen … find out exactly what happened to him, why firemen didn't hear his PASS device.

"When I got the report ... it said nothing about anything except certain things about what other firemen did or didn't do. It didn't go to the reason why Rob died."

Even in Worcester, Mass., where six firefighters died on Dec. 3, 1999, the CDC managers didn't want to send anyone immediately to investigate, said Schmidt, the former CDC fire prevention engineer. He said he called a CDC manager at home.

"And his comment to me was, ‘Well, that's not what we do. We'll get up there in a couple of weeks,’” Schmidt said. “But the next day, I see that they'd all left to go up there."

Castillo confirmed that the CDC went to Worcester immediately, only because the firefighter union called. Duffy, the union official, says he had the home number of Linda Rosenstock, the director of NIOSH.

"We called and said, ‘You guys have to be here,’” he said. “… I believed it was important for them to be there. There's a brand new branch to investigate firefighter fatalities, and we have six firefighters down.”

The CDC sent three people to Worcester the next day. Castillo, the manager of the program, said she wasn't sure whom Duffy called but confirmed his basic account. Rosenstock, who has since left the CDC, declined a request for an interview.

Then the CDC went right back to taking a month or longer to visit fire scenes, according to the CDC records reviewed by msnbc.com.

Castillo said that a delay in visiting the scenes of deadly fires doesn’t mean the agency isn’t investigating. Members of her unit quickly begin making phone calls to line up the visit and gather information, she said. And she said taking time is more respectful to the family and the fire department, to allow time for funerals before investigators arrive.

Monday-Friday, 9-5

Although firefighters can and do die at any time of any day of the week, the CDC doesn't do much investigating on nights or weekends. The firefighter program reports indicate that while 43 firefighters died on weekends from 1998 through 2006, the CDC unit started only six site visits on Saturday or Sunday.

The CDC manual also urges investigators to limit their work days in the field to an eight-hour day.

By contrast, the NTSB manual encourages the investigators to leave within two hours and to work the case vigorously, with meetings from 7:30 a.m. to as late as necessary.

Fewer cases

At its measured pace, the CDC doesn't investigate every firefighter death. And last summer, it proposed reducing the number of cases that it does examine.

But without notice, it already had done so.

Msnbc.com combed through the Fire Administration's list of line-of-duty deaths from 1998 through 2006, to eliminate heart attacks and vehicle accidents and to make sure that every remaining death was one that the CDC would hear about. Then it compared that list against the CDC unit's investigations database and fatality reports, and asked the agency to update the database with any investigations in progress.

The results:

- From 1998 through 2003, the CDC investigated 89 percent of the fire scene fatalities, or 73 out of 82.

- From 2004 through 2006, the CDC investigated only 70 percent of the deaths, or 23 out of 33.

The firefighters union contends that Congress wanted every death investigated.

"Our belief is the congressional intent was that they go to every one, but Congress didn't give them the money," Duffy said.

NTSB comparison called invalid

Castillo said CDC has neither the money nor the mission to look into every death. “We did not get specific guidance, nor do we have the resources, to investigate every single firefighter death," she said. She said the CDC's $2.5 million budget for firefighter investigations is dwarfed by the $75 million that Congress gives to the NTSB each year.

Besides, the CDC has said, the conclusions of its investigations have become repetitive. Last summer, when it proposed scaling back, the agency stated that investigators "are finding similar contributory factors, and consequently repeating prevention recommendations made in previous investigations."

The CDC sought public comment last summer on a proposed change: investigating fewer specific incidents, freeing it to focus more time on databases and topical reports, such as firefighters who die of heart attacks, vehicle accidents, training accidents, and risk-vs.-reward decisions when fighting fires.

After encountering strong opposition at a public meeting to the idea of fewer investigations, the CDC abandoned the idea, Castillo told msnbc.com. She said that the agency now plans to keep the investigations at the current level.

At that public meeting, a prominent fire chief and author of a text on firefighting encouraged the CDC to take a more scientific approach. Edward Hartin, a battalion chief in Gresham, Ore., said the investigations have been of substantial benefit to firefighters, but "there are some gaps in the information provided by these reports." He said he would like to see more information about the environment that the firefighters were working in — the building, the fire, the smoke, the heat — so better lessons could be learned about whether the firefighters made good decisions.

Only with cooperation

Unlike the NTSB, the CDC says it goes only where it's invited.

If the fire department or the union objects to having the deaths studied, the CDC backs off.

"There are times," Castillo said, "that we go out to do an investigation, we do not get cooperation. When that happens, we do not do the investigation. We have never pushed to do an investigation in that situation. ... The NTSB has specific authority to secure a site, to subpoena witnesses. ... We don't have that. We are relying on cooperation with the fire department. We have found it to be pretty successful. It's not a common event that they refuse cooperation.

"We were provided with funding for the firefighter initiative. We were not provided with statutory authority like other agencies such as the National Transportation Safety Board," Castillo said. "For example, we don't have statutory authority to enter and inspect a site, to obtain records, to perform tests, or order or obtain an autopsy for the purposes of investigation. What we do is we work with the fire department. ... We can only go when we have the cooperation from the parties that are involved."

At first, Castillo told msnbc.com that the CDC doesn't have the right of entry to a death scene and hasn't sought it. Then she said she wasn't sure and would have to ask the CDC lawyers. In any case, she said, if the CDC has that right, it wouldn't use it very often.

"From our perspective and the feedback we are receiving from the majority of our stakeholders, our sense is that we are doing a good job, that the fire service is finding our investigations valuable for them," Castillo said. "Even if we have the authority, the agency as a whole uses it very judiciously."

Some deaths go unexamined

The CDC doesn't say which firefighter deaths it takes a pass on.

Msnbc.com compiled its own list and found 19 firefighters from January 1999 through November 2006 whose deaths fighting fires were not investigated.

Duffy, the union safety chief, said the CDC should list every fatality on its Web site and say which ones it's not investigating.

That would be a major shift for the CDC, which doesn't identify the community or the firefighters in its reports. Confidentiality is a valued tradition in medical research, so it lists the deaths only by state and date.

But firefighter deaths are highly public events, so when the CDC reports six career firefighters were killed in a cold-storage and warehouse building fire in Massachusetts, every member of the fire service and many other citizens know that is code for "Worcester."

Shredding files

When the CDC finally acted in 2005 on the problem of PASS devices, the “man-down” alarms, it sent its public investigative reports to the National Fire Protection Association, urging it to consider raising standards.

Although the CDC told the association of five firefighter deaths that occurred where PASS alarms weren't heard, msnbc.com found 15 in its review of the agency’s reports.

The CDC didn't identify the manufacturers, say when the alarms were made, or how they were maintained.

The CDC didn't say, because it didn't know.

The CDC investigators don't collect the same information in every fire about firefighter equipment or clothing. Castillo said it is left to individual investigators to judge which information to collect on each case.

And once the information is collected, the CDC often destroys it.

Castillo confirmed that the program keeps only the information in the reports it issues on firefighter deaths and the information in the CDC's investigations database. But msnbc.com found that neither of those repositories has information on the make or model of PASS devices, or boots, hose lines, fire engines or any other gear that firefighters rely on — except for air supplies, for which the CDC is the certifying agency.

For PASS devices, Castillo said, "at the time that we did the investigation, we knew who made them. We do not have a record of those manufacturers. The issues that we helped uncover are not specific to an individual manufacturer; they speak to the standard the manufacturer was tested against, across a variety."

But how would CDC know if a problem was limited to a specific make or model or year if it doesn't keep that information?

"When they publish a report, they shred all the backup information," said Schmidt, the former CDC fire protection engineer. "They keep no files. You can't go back and look at past incidents. If we get a FOIA (Freedom of Information Act request), all we want to be able to do is to put the report in an envelope.

"… A comment that I heard from one of the managers at the time was, 'We don't want any widows' attorneys coming and looking at our information to build a case.' I was really offended by that. If there’s some firefighter’s widow, they deserve to hear the truth."

Castillo didn't deny that managers had said that, or something similar, but she said that concern about protecting fire departments or manufacturers from lawsuits is "not driving our investigations."

Autopsy? No thanks

In "performance guidelines" given to Schmidt in 2000, Castillo urged him to "minimize your fact gathering during investigations" and to focus only on the information necessary to explain the events that led to a death.

She scolded Schmidt for "your persistence in gathering complete autopsy reports, rather than simply getting information from the report on the cause of death." She pointed out that a manager of the program was more skilled and was able to make a phone call to get the cause of death without getting the report.

Fire departments have been told repeatedly to request an autopsy in every firefighter death, so lessons might emerge that could improve safety. That's been the advice from the International Association of Fire Chiefs, the National Fire Protection Association, the U.S. Fire Administration — and the CDC itself.

Schmidt said he had wanted autopsies so he could see, for example, whether the victim’s hands were burned, which would indicate that the firefighter took his gloves off. An autopsy also could show whether the firefighter was hampered by an underlying medical condition.

Castillo said it's still optional for her investigators to gather autopsy records, because they might not always be useful. In writing to Schmidt, she tied the limitation to privacy concerns: "Given limits on NIOSH's ability to protect information that is provided to us during the course of investigations, efforts are made to minimize information in our files with direct identifiers of individuals."

Neglected database

The CDC has boasted on its Web site about its investigations database, which Congress required it to set up. The CDC called it "a valuable tool to identify trends and analyze risk factors among line-of-duty injury deaths."

But msnbc.com found that the database was riddled with errors that contradicted the official reports on incidents, and that it had been updated infrequently in recent years. The fire that killed Rob Morrison and fellow firefighter Derek Martin in St. Louis isn't in the database.

When the CDC was asked to cite any instances when the database had been used to identify trends or analyze risk factors, the agency removed any mention of the database from its Web site.

"We have recognized," Castillo said, "that the database has not lived up to its potential, and we are in the process of doing a critical evaluation of it."

In its present form, the database has no place to record the training that incident commanders have undergone, and no place to record information on equipment — aside from the air supplies, which the CDC certifies as meeting the national standard.

"If you were a reporter and you were doing a story on an airplane crash," Schmidt said, "you could call up the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) or the NTSB and say, how many times has this engine been involved, and someone would say, ‘We’ve had four previous crashes.’ If you would do the same thing, can you tell me how many PASS devices had failed, they couldn’t do that."

Collecting the facts

Since Schmidt was fired in 2000, the CDC program has not hired another fire safety engineer. It has safety and occupational health specialists performing the firefighter investigations. Several do have experience and training as firefighters.

Schmidt said the underlying problem is that in 1998, Congress handed the CDC a role it hadn't asked for and may not have been trained for.

"They would spend a lot of time talking to the firefighters … and then they would write the report," he said. "… They would come back to the office, and say, ‘Which firefighter do you think was the most credible one there?’ — and benchmark everything against what that firefighter said.

"… So I would try — and this is where we were having a lot of disagreement — let's take a look at that hose, let's measure the burn mark on it, so it will tell us what position the hose was in, and that would tell us how far the firefighter got into the room. They would say, they told you. But how do you know they're right?"

Schmidt said that when he wanted to point out how inadequate a fire department's training budget was, "I had to literally argue my point, go into the office of the deputy director. They would say, 'You can’t talk about it, because you’ll be upsetting the local community. It’s a local decision.'

"That was troubling and perplexing, and to have managers say, don't follow up on that, don't look at the equipment, don't look at fire hoses that have failed, don't listen to the audiotapes — it creates a situation where the investigators don't know what to say or write because they don't understand what the managers are looking for. Because on one hand you have a procedure, and on one hand you have what the managers are telling you to say and not to say."

Castillo said her guidance to Schmidt to "minimize" investigations was directed particularly at an inefficient employee and does not reflect her general orders for the staff.

Castillo told msnbc.com the CDC doesn't need another fire protection engineer.

"This is not an expertise that we have a need for consistently," she said. "When we don't think we have the expertise that's needed, we consult with external experts as warranted."

Both union and management want more

Last summer the a leader of the International Association of Fire Chiefs, I. David Daniels, asked the CDC to do more: investigate more of the firefighter deaths each year, especially deaths from trauma at fires; and add more information to the investigative reports, particularly on the culture in the fire department on risks vs. rewards.

The firefighters have a similar wish list. The firefighters union has long had issues with the way deaths are investigated. Now it has more friends in high places in the new Democratic-led Congress.

Duffy said the union will push this year for lawmakers to give the CDC additional funding to investigate every firefighter death; give notice if it decides not to investigate a death; institute a follow-up program to determine if fire departments implement safety recommendations; identify departments and individuals in its reports, and pay more attention to the forensic aspects of fire-scene investigations — "evidence gathering, mapping where the evidence is, chain of custody, examination or testing of the tools.”

But Castillo said the feedback she has heard leads her to believe that members of the fire service are pleased with the way the CDC is investigating firefighter deaths now.

"We have a tremendous amount of pride about the firefighter program," she said. "We think this is a flagship program and that we have made important contributions to firefighter safety."