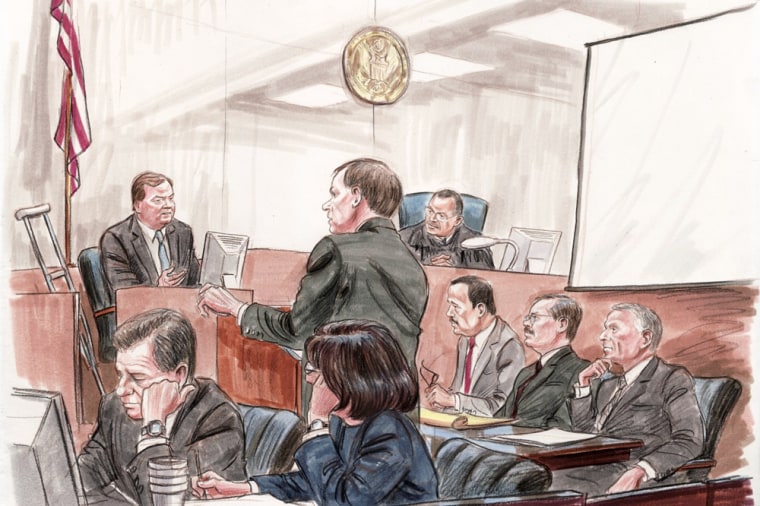

NBC newsman Tim Russert, who drew the biggest audience of Washington's hottest new courtroom reality drama when he took the stand on Wednesday, testified against former White House aide I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby on a key part of his defense.

The host of "Meet the Press" was to be the final government witness in a trial that for three weeks has provided a rare glimpse into the Bush administration and occasionally offered entertainment and gossip for news and political junkies.

Speaking before a packed courtroom, Russert said he never discussed a CIA operative during a July 2003 phone conversation with Libby. Libby has testified that, at the end of the call, Russert brought up war critic Joseph Wilson and mentioned that Wilson's wife worked for the CIA.

"That would be impossible," Russert testified Wednesday about such an exchange. "I didn't know who that person was until several days later."

(MSNBC.com is a joint venture between Microsoft and NBC Universal.)

Unlike previous witnesses who discussed the tense atmosphere inside the West Wing and revealed some of the administration's press strategies, Russert offered little in the way of fireworks. But the discrepancy between his account and Libby's is at the heart of the perjury and obstruction trial.

Libby is accused of lying to investigators about his conversations with reporters regarding Wilson's wife, CIA operative Valerie Plame.

During Libby's 2004 grand jury testimony, he said Russert told him "all the reporters know" that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA. Libby now acknowledges he had learned about Plame a month earlier from his boss, Vice President Dick Cheney, but says he had forgotten about it and learned it again from Russert as if new.

Libby subsequently repeated the information about Plame to other journalists, always with the caveat that he had heard it from reporters, he has said. Prosecutors say Libby concocted the Russert conversation to shield him from prosecution for revealing information from government sources.

Defense questions Russert’s claim

Plame's identity was leaked shortly after her husband began accusing the Bush administration of doctoring prewar intelligence on Iraq. The controversy over the faulty intelligence was a major story in mid-2003.

Given that news climate, defense attorney Theodore Wells was skeptical about Russert's account.

"You have the chief of staff of the vice president of the United States on the telephone and you don't ask him one question about it?" Wells asked. He followed up moments later with, "As a newsperson who's known for being aggressive and going after the facts, you wouldn't have asked him about the biggest stories in the world that week?"

"What happened is exactly what I told you," Russert replied.

Russert originally told the FBI that he couldn't rule out discussing Wilson with Libby but had no recollection of it, according to an FBI report Wells read in court. Russert said Wednesday he did not believe he said that.

Special Prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald has spent weeks making the case that Libby was preoccupied with discrediting Wilson. Several former White House, CIA and State Department officials testified that Libby discussed Plame with them — all before the Russert conversation.

Fitzgerald has said Russert would be his final witness. Prosecutors spent the past few days playing audiotapes of Libby's grand jury testimony in court. In the final hours of those tapes Wednesday, Libby described a tense mood in the White House as the leak investigation began.

Though President Bush was publicly stating that nobody in the White House was involved in the leak, Libby knew that he himself had spoken to several reporters about Plame. He said he did not bring that up with Bush and was uncertain whether he discussed it with Cheney.

Libby remembered one conversation with Cheney, however, in which the vice president seemed surprised when told by his aide where Libby had learned Plame's identity.

"From me?" Cheney asked, tilting his head, Libby recalled.

Libby says notes triggered memory

Libby said he had forgotten that Cheney was his original source until finding his own handwritten notes on the conversation. The notes predated the Russert phone call by a month.

Libby said on Wednesday that he had asked Cheney twice if he wanted to hear details about Plame and Wilson that he Libby had heard in conversations with reporters.

"I would have been happy to unburden myself of it," he said in court. "He didn't want to hear it."

"We shouldn't talk about the details of this case," Cheney said, according to Libby.

Libby also said on Wednesday that Bush told the White House cabinet room on October 7, 2003, "I've constantly expressed my displeasure with leaks." He said he was aware the president had asked officials to come forward.

Russert's grand jury testimony questioned

Fitzgerald, in a court filing early Wednesday, wrote of the Libby-Russert phone conversation, "Mr. Russert will testify that, during this conversation, neither he nor the defendant made any mention of Valerie Plame Wilson or her employment at the CIA."

In the audiotapes played Tuesday during the trial, Libby told the grand jury in March 2004, "It seemed to me as if I was learning it for the first time" when, according to his account, Russert told him about Plame on July 10 or 11, 2003. Only later, when looking at his calendar and notes, Libby said, did he remember that he actually learned the information from Cheney in a telephone conversation on June 12, 2003.

Fitzgerald also addressed an issue that Libby's defense attorneys brought up in court, asking prosecutors to disclose any accommodations that were offered to Russert in obtaining his testimony in the course of the grand jury investigation.

The special counsel wrote that the government requested that Russert voluntarily cooperate by testifying before the grand jury. Russert, through counsel, "sought to avoid providing testimony," Fitzgerald wrote. Russert's attorneys first attempted to convince Fitzgerald that he had nothing relevant to say because he had not been the recipient of any leak regarding Plame's employment. Russert then filed a motion, under seal, to quash the grand jury subpoena issued for his testimony.

After Russert's motion was denied on July 21, 2004, the special counsel and Russert's attorneys agreed on a procedure in which he would forgo an appeal and provide testimony.

The questioning of Russert, according to prosecutors, "… was limited to telephone conversation(s) between Mr. Libby and Mr. Russert on or about July 10, 2003," and any follow-up conversations which involved Libby complaining to Russert about the on-the-air comments of MSNBC's Chris Matthews. Fitzgerald said Russert was also asked "… whether during that conversation Mr. Russert imparted information concerning the employment of Ambassador Wilson's wife to Mr. Libby, or whether the employment of Mr. Wilson's wife was otherwise discussed in the conversation."

Fitzgerald also stated that "nothing in the government's possession" reflects the existence of "any tacit agreements, incentives or benefits beyond those provided as part of government counsel's efforts to 'accommodate the interests of both the grand jury and the media' as required by the DOJ Guidelines."