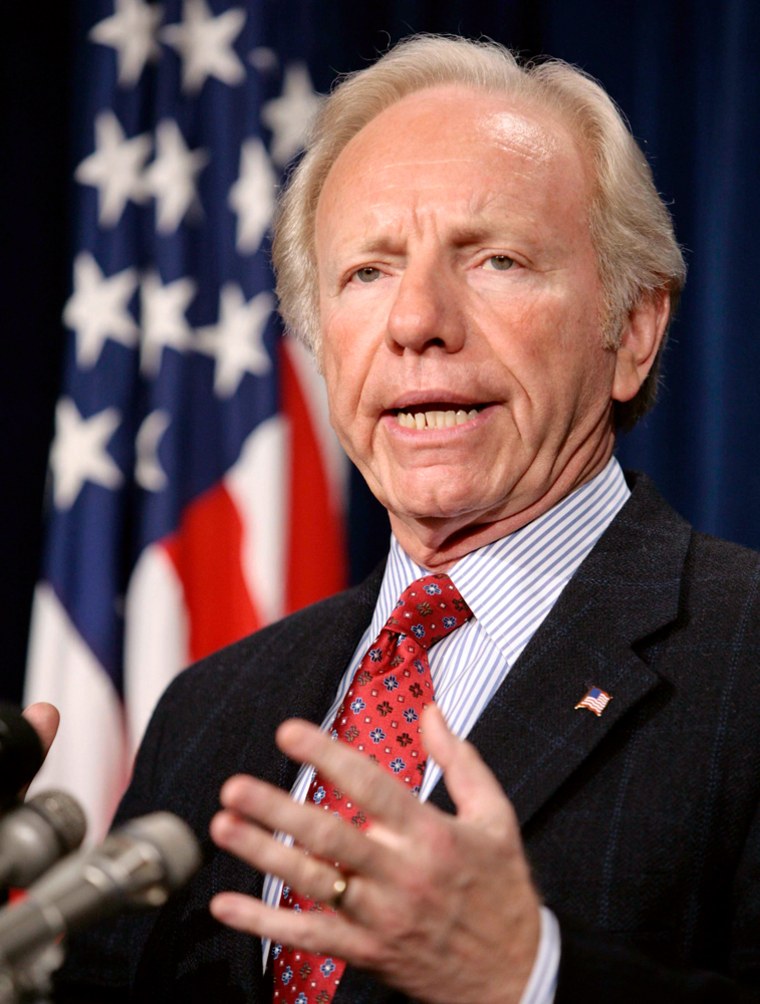

Sen. Joe Lieberman — stalwart supporter of the invasion of Iraq — as the 2004 Democratic presidential nominee?

Unthinkable? In retrospect, yes, but according to the Gallup Poll of 438 Democrats in April 2003 — at a point about where we now are in the 2008 presidential campaign cycle — Lieberman was the Democratic frontrunner.

He got 23 percent of Democrats in the Gallup survey, defeating Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass., who placed second, and an array of other Democrats.

In that poll, Howard Dean, who rocketed to frontrunner status by the autumn of 2003, got the support of only six percent.

Cuomo was the frontrunner

Looking further back, do you recall 1992 Democratic presidential nominee Mario Cuomo?

In February of 1991, again about where we now are in the ’08 cycle, the New York governor was the favorite of Democrats in the Gallup poll, with 17.4 percent, edging Rep. Dick Gephardt at 17.3 percent, and the Rev. Jesse Jackson at 16.6 percent. Statistically the three men were tied and in fact, “none” was the leading choice of Democrats at 22 percent.

At that point in 1992 contest, where was Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton, the ultimate Democratic nominee? A mere three percent of Democrats told the Gallup pollsters they wanted Clinton as their party's candidate. Most had never heard of Clinton.

With ten months to go before voters cast ballots, political junkies are already swamped with polling data. The Lieberman and Cuomo examples offer lessons in why it may not make sense to take early polls too seriously.

“National polls are fundamentally a measure of name identification at this stage; that helps a lot with fundraising and with being taken seriously” by the news media. “But it tells you very little about who’s likely to win the primaries on Feb. 5,” said Republican pollster Whit Ayres.

Early states set the tone

In national polls (with a sample size of anywhere from 500 to 1000 people who call themselves registered voters) most of those polled do not live in the handful of states (Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina) that will vote first and will define the battle for the nomination.

If a contender for either party’s nomination fails to make a good showing in Iowa and New Hampshire, he or she will likely be finished. That’s what happened to Dean in 2004.

So one rule of thumb is: pay more attention to polling in the early states of Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina.

“Basically, nothing is very predictive right now, but it's the trends in the early states that will matter most, because what happens in Iowa and New Hampshire will ultimately drive the national numbers,” said Democratic pollster Mark Blumenthal, who is the editor and publisher of the Pollster.com web site.

“The national numbers will matter — during the week leading up to Feb. 5,” (when several large states such as California and Illinois will likely have their primaries), he said. “But until then, watching them is mostly an insider's game.”

He added, “The first priority for a national campaign is to not to go out and do a big national survey, but to go to Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada. That’s where the process starts. If you’re a candidate, the place you want to do research is the place where you can affect the process.”

Unlike 1992, where in the Democratic field, there was one celebrity possible contender, Cuomo, who lingered on the sidelines, and an array of lesser-known candidates such as Bob Kerrey and Paul Tsongas, this year’s contest has one celebrity frontrunner, Sen. Hillary Clinton, one relatively new alternative, Sen. Barack Obama, one familiar alternative, former Sen. John Edwards, and one lingerer-on-the-sidelines, Al Gore.

The Republican top tier consists of Sen. John McCain, former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani and former Mass Gov. Mitt Romney.

Can a long shot break into top tier?

American Research Group pollster Dick Bennett, who does surveys of New Hampshire voters, says sometimes, though rarely, a lower-tier candidate such as Dean can vault into the top tier. This year, Bennett asked, “Are there Howard Deans out there? We don’t see it. History says that top tier pretty much stays top tier. A Gary Hart is unusual.”

In 1984, Hart used a second place finish in the Iowa caucuses to get media attention and won the New Hampshire primary in an upset over frontrunner Walter Mondale. Hart then won a string of primaries from Florida to Connecticut before Mondale stopped him in New York.

Bennett asked, “The lower-tier candidate has to do something (to get attention). Generally, lightning doesn’t strike for a lower-tier candidate.”

Perhaps the most important audience for polling data at this stage is the universe of donors, strategists, reporters and pundits.

Unlike voters, the donors don’t wait until next December or January to make their decisions on whom to support.

Last week the Keystone Poll at Franklin and Marshall College in Pennsylvania found that if former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani were the GOP presidential nominee and Sen. Hillary Clinton the Democratic nominee, he’d beat her easily in Pennsylvania, 53 percent to 37 percent.

In a hypothetical match up between Giuliani and Obama, Giuliani did even better, winning 52 percent to 32 percent.

Pennsylvania is a key state in presidential elections: since World War II, only one Democratic candidate has been able to win the White House without winning Pennsylvania. (That was Harry Truman in 1948)

The Keystone poll may register with Republican donors and strategists because it provides empirical support for the argument that Giuliani supporters have been making: the former New York mayor would radically change the Electoral College calculus and force Democrats to defend states they’ve been able to take for granted in every recent presidential election.

So for that reason the Pennsylvania data — admittedly as premature as all the other polling data — has a certain value.