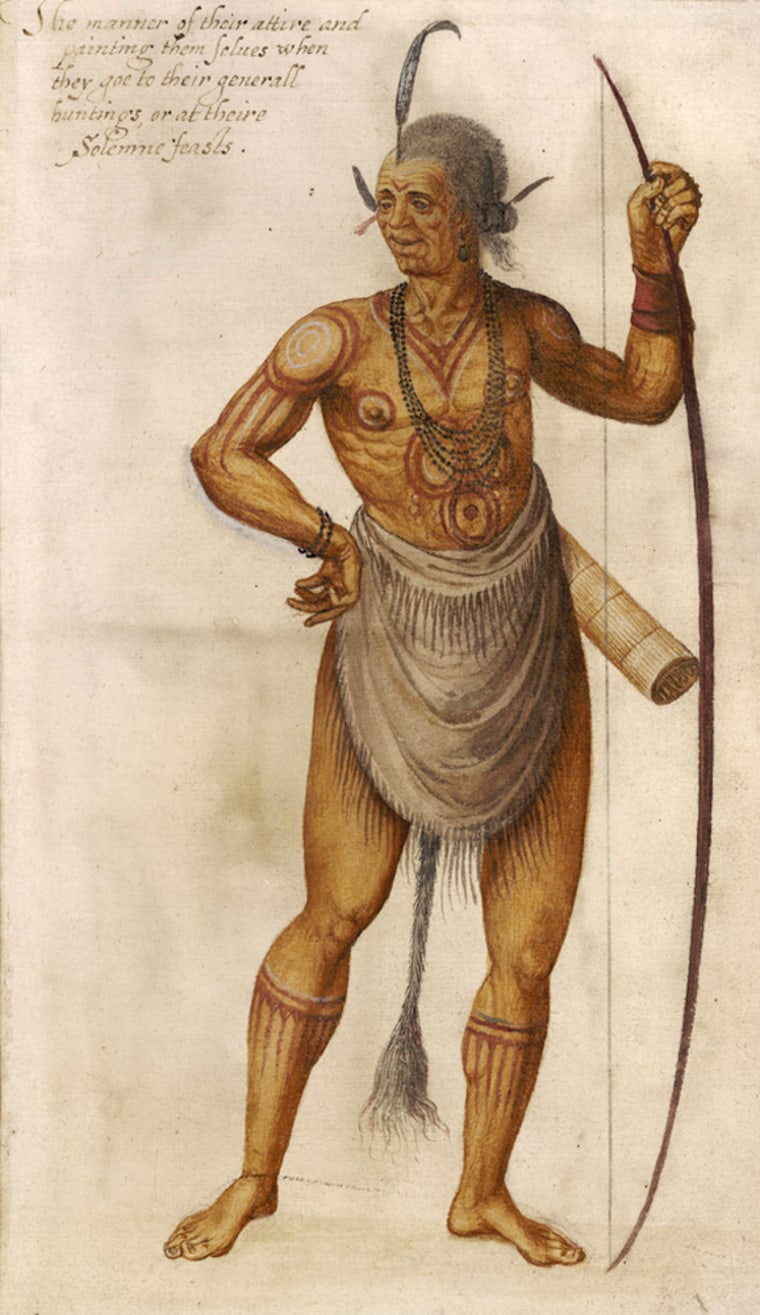

The American Indian chief — strong, lithe and elegantly tattooed — gazes calmly toward the viewer in a portrait by a 16th-century Englishman.

The watercolor in a major new British Museum exhibition captures a moment of first contact between two cultures, and a glimmer of illumination before a dark historical episode. The artist, John White, went on to become governor of the first attempt at a permanent English settlement in the Americas — the “lost colony” of Roanoke, whose settlers disappeared, their fate still unknown.

White made his drawings during an 1585 expedition to the land the English dubbed Virginia in honor of their “virgin queen,” Elizabeth I — modern-day North Carolina. They show “images of the people of North America before they had been in touch with any English people, villages that had never seen any Europeans before,” said the exhibition’s curator, Kim Sloan.

“They are what we call ’first contact’ images,” she said.

White’s portraits of the Algonquin people — among the only surviving images of 16th-century North America — are the centerpiece of the British Museum’s show, “A New World.”

The subjects appear dignified, in cloaks and elaborate tattoos. The women have earrings, fine necklaces and body paint.

White drew tidy villages with communal houses and temples, ceremonial dances, men spear-fishing from dugout canoes and domestic scenes, including a couple eating corn from a wooden platter.

“It’s a very sympathetic portrayal,” said Sloan.

That’s unsurprising, since the pictures were designed to reassure prospective settlers and investors about the inhabitants of the New World.

As a contrast, the exhibition offers images of fearsome-looking Pictish warriors — ancient Scots — also found among White’s drawings.

“The Pictish women are carrying spears. The women here are carrying children, their tattoos are beautiful,” Sloan said. “The village almost looks like an English village, with a country lane.”

White also produced finely detailed illustrations in pencil and watercolor of the flora and fauna he found on his voyages to the New World. There are scorpions and hermit crabs, crocodiles and flamingoes, plantain and pineapples, all rendered in exuberant detail.

White’s drawings were acquired by the museum in the 19th century after being damaged in a fire at the warehouse of Sotheby’s auction house. Water damage after the fire leached some of the pigment — and the rich touches of real gold and silver — from the drawings, but they remain remarkably vivid.

The fresh and colorful pictures hide the dark side of the encounter between cultures.

The members of White’s 1585 expedition soon clashed with the local population, setting fire to a village and murdering a local chief, Wingina. The show includes a portrait by White thought to be of the ill-fated man.

White had returned to England and, using his drawings as part of the propaganda push, recruited 115 settlers for a permanent colony.

The colonists included White’s pregnant daughter, Elinor, and her husband, Ananias Dare. Their daughter, Virginia Dare, was the first English child born in the Americas.

The group had intended to settle at Chesapeake, in present-day Virginia, but were forced by lack of supplies to land on Roanoke Island in 1587.

White set out for England in search of assistance. By the time he returned to Roanoke in 1590, the settlers were gone. Some historians suspect they were all killed, or taken as slaves; others speculate they moved to another island and gradually intermingled with the local population.

“There are as many theories about what happened to them as there have been books written on them,” said Sloan.

The first permanent English settlement in the Americas was eventually established at Jamestown, 130 miles to the north, in 1607.

The impact of White’s drawings — reproduced in widely published engravings by Flemish artist Theodor de Bry — long outlasted his ill-fated colony.

Among Europeans, Sloan said, “John White’s images came to stand for the Native American people for the next 200 years.”

“A New World” is at the British Museum until June 17.