If an outhouse on the moon ran out of toilet paper, an intrepid settler might have to waddle about 240,000 miles to get a fresh roll back on Earth.

To make sure that doesn't happen, scientists have developed a software tool that tracks and ensures a reliable stream of necessities from the Earth to the moon.

Released this month, the computer model, called SpaceNet 1.3, will be critical, say the scientists, for establishing a human presence on the Moon by 2020, as laid out in the space vision by President George W. Bush in 2004.

“The further away you get from Earth, the riskier it gets when there are failures of any equipment or shortages of consumables,” said co-researcher Olivier de Weck of MIT. “There aren’t many back-up options.”

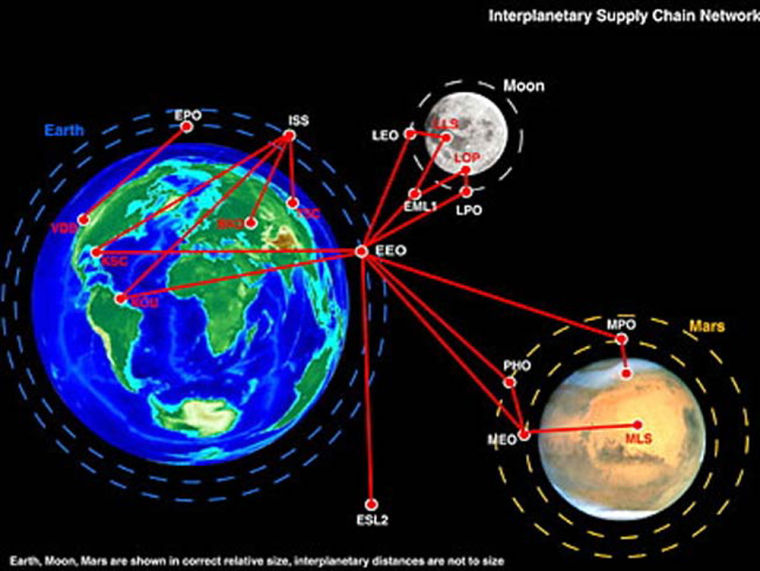

De Weck and MIT’s David Simchi-Levi developed SpaceNet. The software evaluates several hypothetical missions to the moon, with each building upon the previous. It’s set up as a network of nodes that represent either a source of materials, point of consumption or transfer point for space exploration logistics.

The resulting supply chain would operate similarly to the flow of materials on terra firma. But unlike Earth-based delivery service that can suffer delays of hours or days, goods headed to the moon could easily be months late. Just witness the frequent delays in getting a shuttle to the International Space Station, which is just a little more than 200 miles away. Plus, shipping capacity will be extremely limited for the expensive, three-day one-way trip to the moon.

De Weck describes the dilemma in Earthly terms. “If I sent you on a one-month trip, and I said you can only pack what fits into your glove compartment, you would probably still go,” De Weck said, “but you’d have a really hard time [trying] to pick what to take with you because there are all of these competing demands.”

To help make these decisions when packing the lunar version of a glove compartment, the scientists divided supplies into three categories: consumables—such as food, fuel and water —spare parts and exploration equipment. Like any packing vacationer, planners with limited space and delivery opportunities will have to make difficult trade-offs between competing demands for each type of supply.

“For example, you could stay for a shorter time, have fewer crew days and bring more equipment with you. Or you bring less equipment with you but then you stay longer, and that will require more consumables,” De Weck said.

The scientists will continue to refine and expand SpaceNet, which they say will ultimately also include a Martian framework analogous to the lunar version of the software. In another project, De Weck said they are developing smart containers implanted with electronic tags to keep track of each shipped item. Of course, the containers would have the ability to signal to Earth when consumables, such as toilet paper, are running low.