The murky rivers around New York City bring to mind many things — garbage, chemicals, perhaps mobsters' bodies. Clean energy is not one of them.

But the state is trying to change that thinking.

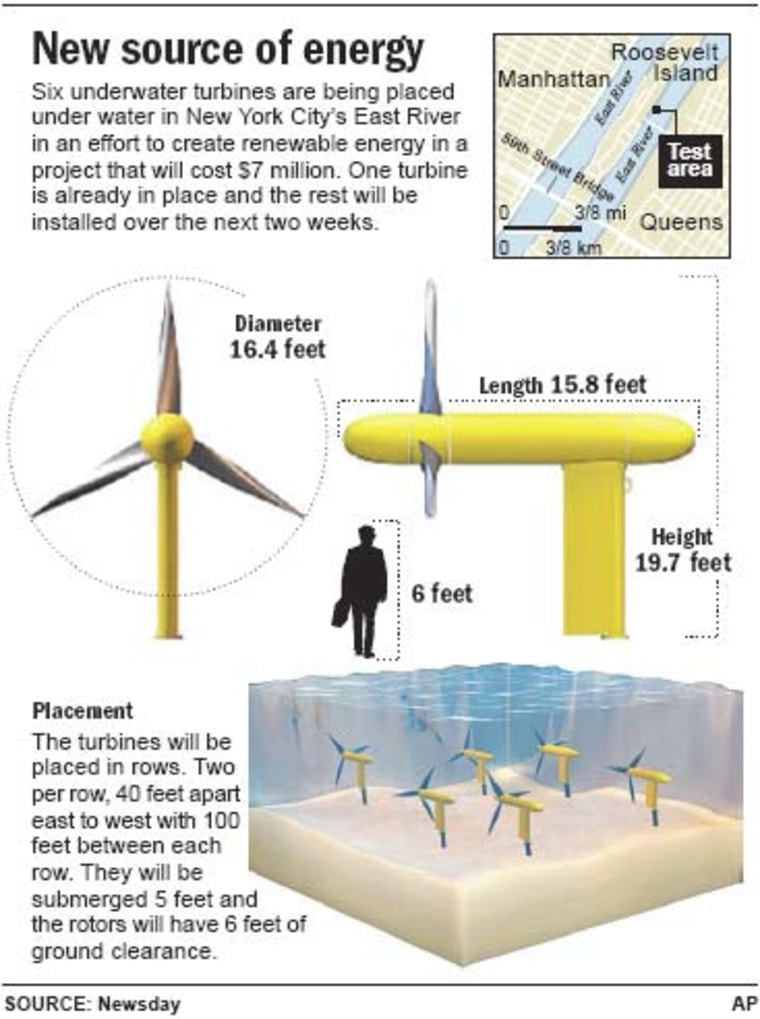

It is teaming up with a Virginia company to use the East River for a unique experiment in renewable energy: Six giant turbines are being placed underwater in a $7 million project to harness the energy of the tides and produce electricity.

One of the 16-foot-diameter, windmill-like turbines is already operating, supplying power to a grocery store and a garage on Roosevelt Island. The other turbines are being installed by early May.

"We're looking for the most cost-effective way to get the most energy out of moving water while having a positive impact on the environment," said Verdant Power President Trey Taylor.

Hydroelectric and wind power operate on similar principles, with water or air turning turbines. But those projects require dams or windmills, which can be costly, intrusive and objectionable to environmentalists.

Project organizers say this is the first time the underwater-turbine concept has been used in the U.S.

"We picked New York on purpose, because the regulations are so strict, and because the East River is a tidal strait, there is a high current," Taylor said. "You know what they say about New York: If you can make it here ... "

The project is now entering an 18-month testing phase. Its backers hope to expand use of the technology in New York if it works out.

One downside is that the river sometimes moves too slowly. On average, the turbines rotate enough to generate electricity only about 77 percent of the time. At full capacity, the 10-megawatt project could power 10,000 homes.

That is not much in a city of 8 million people, but it's a step in the right direction, environmentalists say.

"The biggest source of power is burning oil, coal and all of that," Taylor said. "That contributes to greenhouse gases, and in a city where this many people live, the idea of having a clean energy source is a real appeal."

Fish concerns

Some environmentalists worry the project may harm fish by stirring up sediment or otherwise altering their habits. The river isn't quite the cesspool it was 30 years ago, and is home to striped bass, herring, smelt and sturgeon, many of which travel between the ocean and the river.

Taylor said the fish near the turbines are being monitored with sonar equipment, and the river bottom is mostly bedrock, so no sediment is being churned up. Commercial vessels do not use that section of the river, so shipping is unaffected.

Environmental groups would like to see a year's worth of data before deciding whether the 8,500-pound, steel-alloy turbines have any significant effects, but so far, they are pleased.

"The idea that it is renewable energy is a really good thing," said Robert Goldstein of the environmental group Riverkeeper. "They seem to be acting very careful and moving forward in a responsible way."

State optimistic

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority has provided nearly $2 million toward design and environmental testing.

"We've had some blade failures, but we've already gotten back some great test results," said Ray Hull, a spokesman for the authority. "This could be a significant advance in renewable energy."

Hull said the economics are hard to ignore, too: "During high tide periods in July and August, when there is such a demand for power, this could be pretty good stuff, financially speaking."

Taylor is thinking bigger. He wants to place the technology in U.S. rivers like the St. Lawrence or the Mississippi, and around the world.

"There are so many people that don't have access to electricity around the world," he said. "But many live near running water."