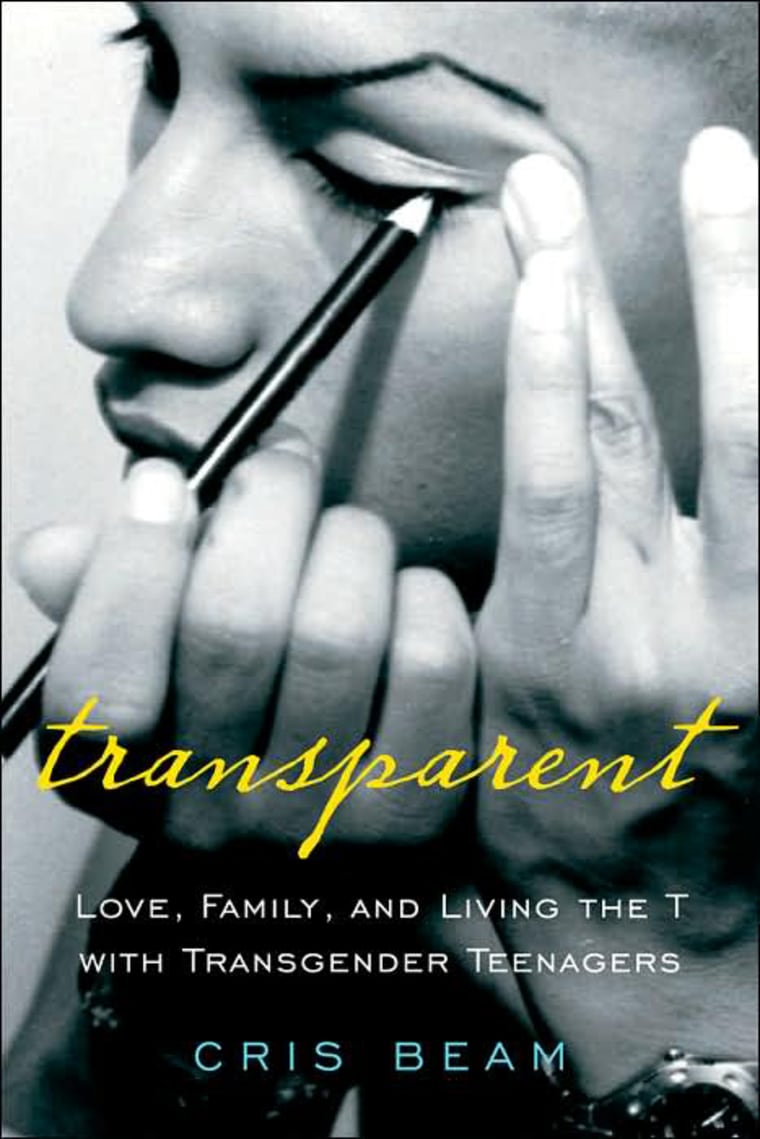

Cris Beam wrote “Transparent: Love, Family, and Living the T with Transgender Teenagers” after volunteering at a school for gay and transgender students in Los Angeles, and becoming a foster parent to one of her students. Cris is a journalist and lives in New York City. You can read an excerpt of her book below.

The first really great drag mother I ever met is a woman named Foxxjazell. Foxx was twenty years old when she first called me; she heard I was researching young transpeople for a book, and she wanted to be included in the project. Foxx grew up Dwight Eric in Birmingham, Alabama, and had bused her way to Los Angeles as soon as she graduated from high school and had scraped together enough fare for the trip. She wanted to be a musician or, as she said, “the first really big international transsexual pop star.”

“You’d better hurry up,” Foxx told me in our initial telephone conversation. “I’m going to be a major star, I’d say, within three years, so if you want a shot at writing my biography, you’d better get to know me now.” She was young and confident and sounded more naive than vain when she described herself so I could recognize her when we met.

“I’m very beautiful,” she said. “I’m tall and black, with butter pecan chocolate skin and long silky hair.” She suggested we meet at the Red Lobster.

I recognized Foxx immediately when she loped through the door. She was right—she was pretty, with silver charms woven through her hair and ripped tight jeans, upon which she had scrawled the words “Latins Do It Better.” She moved her tall body slowly, like she was accustomed to being watched, and the men in the restaurant did indeed scroll their eyes up and down her figure while the women tightened their jaws. A waiter stumbled as he led us to our table.

Over a well-done steak slathered with ketchup, Foxx told me the story of her own drag mother, a drag queen named Tatiana, whom she had met only a year and a half before. Foxx had just arrived in Los Angeles, as a femmy eighteen-year-old gay boy, and was staying at a shelter for young adults called Covenant House. While hanging out in Covenant’s living room, Foxx watched a young woman with a cropped bob haircut and a summer skirt slip through the door, tossing her head and laughing with friends.

“When I first saw Tatiana, she was wearing high heels and her makeup was so fierce,” Foxx remembered. “But I couldn’t catch T; I couldn’t catch the fact that she was really a boy.”

“T” is a letter-word that urban transkids use for all kinds of circumstances. It stands, of course, for transgender, but it also stands for “truth.” When a kid says, “Here’s the T,” she means, Be quiet and listen: I’m about to get real. This, I think, is remarkable. The letter that has come to signify difference—T—also means total honesty. Somebody might say, “I didn’t spill my T,” which means she didn’t disclose her transsexuality. But she might also say, “What’s his T?”— meaning “What’s the skinny on that guy—what’s the real truth about him?” With this question he might be asking all sorts of things: is he gay, is he from here, is he available, and so on. “What’s the T?” can also be used as a generic greeting—a sort of “Wassup?” for queer kids.

In any case, when Foxx discovered Tatiana’s “T,” she said, “I wanted to have Tatiana’s face; I wanted to have her body. I just wanted to be her.” So Tatiana arranged for Foxx to be her roommate at Covenant, and she shared her girl clothes to dress up in on the weekends. Tatiana taught Foxx how to do hair extensions and gave her countless makeup tips, including how to shade her cheekbones and run concealer down her neck to diminish her Adam’s apple. Foxx had been dressing as a girl intermittently throughout her childhood, but mostly, because of her inexperience and lack of access to feminine things, she didn’t pass. She dressed up privately in her bedroom; when she went out, she was alone and it was night, and she made sure no one could see her.

But with Tatiana, Foxx told me, she could go further. She no longer had parents to sneak around, and Tatiana hustled on the side so she had plenty of cash to share. Tatiana gave Foxx skirts and shoes and the requisite encouragement to walk around in daylight; she told Foxx she looked pretty, that boys would like her, that she didn’t have to live her life as a gay boy. She told her real women could have penises—a radical notion Foxx passes on to her own drag daughters today. “’Cause who are you pleasing if you cut it off ?” Foxx will saucily quip. “Your man or yourself ? Girl, you got to please yourself in this world, and real women can have a little something extra between their legs if they want to.”

This idea was, when I heard it from Foxx, still a little surprising, and I felt a shiver of discomfort run down my spine. I had grown up believing, without thinking about it, that genitals represented sex. That a vagina was female, and that a penis was essentially, inarguably male. How could a girl have a penis? How could a boy not? And if a girl did have a penis, as Foxx suggested, wouldn’t she want to, above all else, get it removed?

I’m glad I kept these thoughts silent as Foxx dunked her deep fried shrimp into little ramekins of ketchup and chattered on. I’m glad I just absorbed the image and let it, over the months, become less foreign. It helped that I met more and more kids who wanted to keep their penises, who didn’t want to chance losing all future sensation in a risky surgery—kids who were proud of their bodies and willing to present, or protect, them as they pleased.

A friend named Michele also helped me to adjust my assumptions. Michele was a lesbian fire captain in Los Angeles, a male-to-female transsexual who transitioned on the job when she as in her forties. Now Michele and her partner Janis run transgender awareness workshops. In their classes they hand out sheets of paper with four lines drawn across them, with an M and an F at opposite ends of each one. The lines are labeled “biological sex,” “gender identity,” “gender expression,” and “sexual orientation”—indicating that these notions aren’t fused—and students are told they can mark a spot on the lines where they think they fall. Most people feel they embody a mix of male and female qualities and will place themselves somewhere more toward the middle on at least some of the continuums. We all float a little.

I also started thinking about accidents and surgeries. A friend had a mastectomy around this time, and while the operation certainly made her feel less sexy, it didn’t make her question her sex. I asked myself if a man lost his penis in some kind of accident, would he be any less male—and, conversely, would I be any less female if I, in an odd hormonal surge, grew one? I began to understand that the brain and the heart are the only organs with a gender, and that all genital modification or lack thereof is simply a personal aesthetic choice.

As the confidence Tatiana instilled took hold, Foxx no longer wanted to dress as a girl part-time. She wanted to live, day and night, as a woman. Foxx told me she was working at a telemarketing firm during this period, and when the company announced they’d be initiating casual Fridays, Foxx leaped at the news. That very next Friday, workers showed up in jeans and khakis. Foxx showed up as a woman.

“It all came down for Foxxjazell. She just couldn’t take just dressing up at night; she couldn’t take just dressing up on weekends. So Dwight Eric had to go,” she explained, adding that while she wasn’t fired from her job, she was required to use an unmarked bathroom

on an abandoned floor of the building. “In a way, it was like I got in the car and I saw Dwight Eric and just ran him over; that’s how I looked at it,” she said. “For a lot of years, I hated Dwight. I hated his short ugly hair. I hated the way no one understood his pain. Foxx is more courageous, more bold.”

Excerpted from TRANSPARENT © 2007 by Cris Beam. Reprinted by arrangement with Harcourt, Inc.

Cris Beam’s website: