Want to go green? Take your thoughts off that gas-guzzling SUV for a moment and consider this: The average U.S. home causes twice as much greenhouse emissions as a single car.

That's right. A typical house requires power for heating, air conditioning, hot water and lighting -- enough to cause the emission of tons of polluting carbon gases each year. A typical house is responsible for the emission of more than three tons of carbon annually, compared with about 1.5 tons for the typical car, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

So it shouldn’t be a surprise that green home building is poised to be the next great sales pitch in America’s environmental renaissance. By 2010, half of new homes built are expected to be classified as “green” as more builders try to appeal to consumers worried about global warming, the environment and rising energy costs. Builders say green homes are more durable and tend to sell much faster than traditionally built houses.

But how do you tell if a “green” home is truly green?

It depends on whom you ask. There are some 80 different local and state green building organizations and at least two different national groups promoting their own rules on what constitutes a green home. The result: a contentious war over whose rules become the national standard for making a house sustainable. It also means more confusion for homebuyers.

“You can’t just go and buy a green home with a magic stamp on it that you know is green,” said Monica Gilchrist, national resource center coordinator for Global Green USA, which helps people walk through the green building process.

Perhaps the best-known group in green building is the U.S. Green Building Council, or USGBC, a nonprofit group that developed its own point rating system for green commercial projects and has certified 800 projects as green since 2000 through its Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design program, or LEED. The organization uses consultants under contract to certify projects according to USGBC rules.

In 2004 the Green Building Council rolled out a pilot program for similar grading of residential projects, and today 350 builders are enrolled for 6,000 green homes to go through LEED certification. To get a home certified as green, builders would have to pay about $2,000 for the required inspection. An official program for green homes should be rolled out this fall.

Meanwhile, the National Association of Home Builders, a trade group with 235,000 corporate members, is at work on its own green buildings standards. The group, which worked a decade ago to develop a standard way to measure square footage in homes, began work on green building rules in 2004. The process has been a long and arduous one, incorporating input from not only builders but architects, interior designers and construction product manufacturers. The rules, being developed in collaboration with the International Code Council, will be written for accreditation from the American National Standards Institute, or ANSI.

“There’s friction between us,” says Jay Hall, acting program manager for the Green Building Council’s LEED for homes program. But, he adds: “I do think we can and should play together.”

Hall and other Green Building Council officials worry the NAHB will come up with watered-down standards of what constitutes green in an attempt to appease too many varied stakeholders, including builders who want to keep costs down.

Calli Schmidt, a spokeswoman for the home builder’s association, argues that the Green Building Council standards shouldn’t be mandatory for builders, because they are not drawn up through consensus and are meant to generate revenue through the certification process.

“It’s a product. It’s like something you buy,” Schmidt said. “It’s a business proposition for them: ‘If you follow our program you will be considered green.’ ”

Generally, construction of green homes produce less waste, and once built, the homes use less energy, less water and fewer natural resources and offer better air quality for people living inside. The homes may include energy-efficient appliances, water efficient faucets, better ductworks and air filtration systems or low-emissivity windows (which keep heat from filtering in or out of the windows). Paint is often a variety with few volatile organic compounds. Builders may even consider a home’s orientation to the sun or the color of its roof as ways to conserve energy.

Homebuyers typically pay 3 to 5 percent more for a “green” home, or about $10,000 extra on $300,000 home. But advocates say the extra costs quickly pay for themselves in savings on water and power.

Green residential projects run the gamut, from individual custom homes to entire green subdivisions, such as the 55-acre Oak Terrace Preserve under way in North Charleston, S.C., which touts its pedestrian-oriented layout, environmentally friendly rainwater drainage systems and 374 energy-efficient homes.

In New York, the residential high-rise is going green. The Albanese Development Corp. is building a 33-story, 250-unit condominium tower in lower Manhattan called The Visionaire, which relies on solar power to cut energy costs and a water conservation system to reduce water usage. Recycled water from bathrooms and kitchens will resupply toilets and provide water for the building’s heating and cooling system. Rainwater will be collected and stored for use on a rooftop garden, which provides additional insulation for the building.

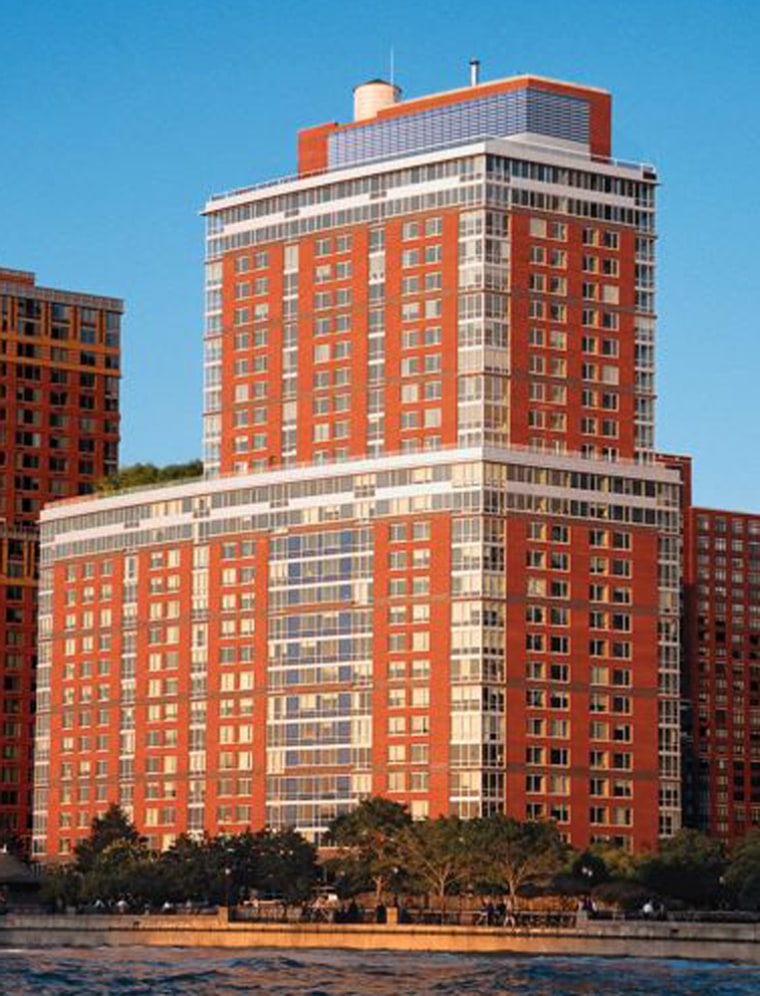

Albanese Development built a similar 27-story apartment complex called the Solaire in 2003 and has several more green high-rise projects planned. “It’s the only way we think right now,” said Michael Gubbins, the company’s president. “It’s about building a better product.”

Polly Brandmeyer notices the difference living in a green building. The 35-year-old mother rents a unit in the Solaire, and she raves about the ventilation system, which, unlike most New York apartments, doesn’t blow in dry heat in the winter that cracks furniture or blow in black grime in the summer. That’s especially nice, she said, since the apartment is near the World Trade Center site with its heavy construction.

“To go back to the old way of living it would be a total setback, a step down,” said Brandmeyer. “We’re happy to have that extra layer of filtration in our building.”

It can be hard to show consumers those kinds of benefits in advance, said John Keith, president of Harvard Communities, which is building 40 green homes this year, most of them on the site of Denver’s former Stapleton Airport.

Much of what makes Harvard Communities' homes green is decidedly unsexy, Keith said, because most of the features are not visible to consumers. Buyers want to talk about granite countertops, not how Harvard uses less wood in framing for better insulation or how contractors are coached on how to better seal windows so air doesn’t escape the house. To pique buyers’ interest, Harvard started including a 2.8-kilowatt rooftop solar system as a standard feature on the homes. “It’s hard to get people excited,” Keith said.

The green features, along with design and location, appealed to Dr. Stephen Leong, a 35-year-old oncologist who bought a $700,000 house from Harvard in April. Leong said he recognizes the toll people are taking on the environment and he likes the idea of controlling rising energy costs. But he didn’t start out searching for a green home. “But once the choice was available, it helped sway my decision,” he said.

Time ultimately will decide which set of rules will become the norm in homebuilding. Until then, home buyers should guard against “greenwashing” by home builders who tout a house as green despite only minimal changes to traditional construction.

Consumers should look for third-party certification and carefully research the standards used by a builder, said Gilchrist of Global Green. Determine your own priorities, she said, such as lowering electricity bills or perhaps improving air quality for an asthmatic child, and then find the rating system that best matches them. Global Green to learn more about various green building certification programs.