Scientists say they have detected the brightest stellar explosion ever recorded, a new breed of supernova that may well be repeated sooner than they previously thought.

The violent explosion was observed by ground-based telescopes as well as NASA's orbiting Chandra X-Ray Observatory in a galaxy far from our own Milky Way. But the observations hint that an erupting star in our own galaxy, called Eta Carinae, could be close to the same kind of blast, astronomers say in a paper to be published in The Astrophysical Journal.

For years, scientists have been looking for a blast this big, but never found one until last September. After months of analysis, the research team discussed their findings at a news conference Monday here at NASA Headquarters.

"We discovered a supernova that stands out as far and away the most powerful, the brightest supernova that has ever been observed," the head of the research team, Nathan Smith of the University of California at Berkeley, told reporters.

"Now that alone is not reason to make it so exciting," he continued. "The reason we're excited about it is that the supernova is so powerful we think it may require a new type of explosion mechanism, that has been predicted theoretically but has never been actually observed before."

The brightness of the supernova, which has been designated SN 2006gy, wasn't that obvious to earthly observers because the star that blew up was 240 million light-years from Earth, in a galaxy called NGC 1260.

But when astronomers took that vast distance into account, they figured that the supernova was 100 times more energetic than usual. Such a phenomenon would require the violent destruction of a star 150 times more massive than our sun — which is near the theoretical limit for a single star's size.

A new twist for theorists

Theorists had thought that stars that big were more likely to collapse into black holes, sucking all their mass into gravitational sinkholes. Another possibility was that the stars might blow away much of their mass, leaving behind a superdense neutron star.

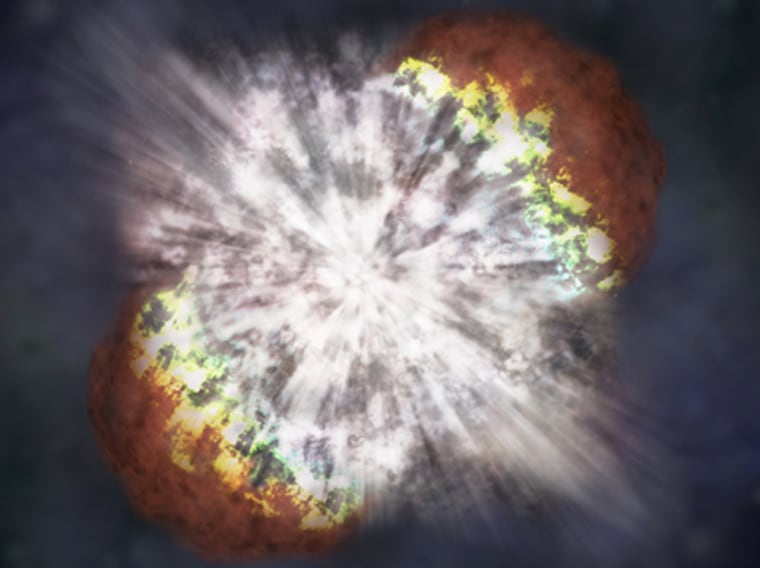

However, the observations of SN 2006gy hint that the biggest stars can go off like giant thermonuclear bombs at the end of their lives. As the star blows up, some of the energy is converted into pairs of matter and antimatter particles, leading to a runaway thermonuclear reaction rather than a black hole.

"This is Einstein's famous equation E=mc2 put into practice," said Mario Livio, a senior astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute. Livio was not part of the supernova research team but said the team's conclusions were plausible.

This process would be completely different from the typical supernova blast, which involves material ejected from the star's core slamming into surrounding hydrogen gas and creating a violent shock wave.

To make sure that the shock-wave mechanism wasn't at work in SN 2006gy, the astronomers compared the observations from ground-based telescopes with Chandra's X-ray readings. They found that the X-ray readings would have had to have been 1,000 times stronger to fit the usual pattern. That's what led the astronomers to conclude that the blast was powered by the runaway thermonuclear process.

A supernova nearby?

Astronomers think many of the universe's first generation of stars were this massive. Thus, SN 2006gy could shed light on how the first stars lived and died.

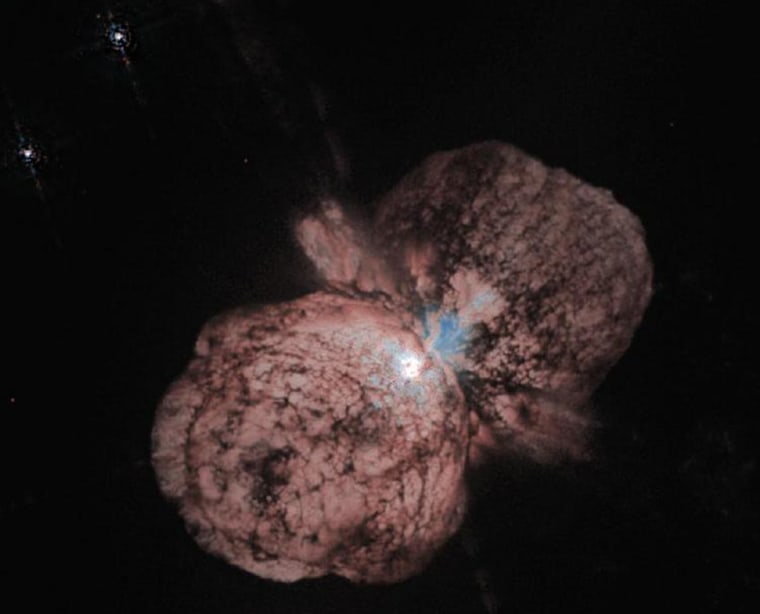

But the findings also raise the possibility that Eta Carinae, the most massive and energetic star observed in our own galaxy, could blow up in the same way. Smith and his colleagues noted that Eta Carinae is roughly the same size as the star behind SN 2006gy, and at roughly the same stage of its life. Eta Carinae, like the star that exploded in the distant galaxy, appears to be shedding huge clouds of hydrogen gas in preparation for a blowup, the astronomers said.

For all its similarities, Eta Carinae is markedly different from SN 2006gy in that it's much closer. Eta Carinae is only 7,500 light-years from Earth, or about 45 quadrillion miles away — which may sound like a long way in earthly terms, but isn't all that distant for a cosmic supernova.

If Eta Carinae were to blow up like SN 2006gy, we'd definitely notice it, said David Pooley, the Berkeley astronomer who was in charge of Chandra's observations.

"It would be so bright that you could see it during the day, and you could even read a book by its light at night," Pooley told reporters.

Scientists had thought that Eta Carinae would have to puff away all its shells of hydrogen before blowing up, a process that could take 100,000 years or more. But Livio noted that the newly proposed mechanism would allow for an explosion at any time.

"This could happen tomorrow or it could happen 1,000 years from now," Livio said.

Astronomers have said a stellar explosion in Earth's celestial neighborhood could touch off a mass extinction — in fact, some scientists have proposed that just such a scenario could explain an extinction that took place 440 million years ago. But Livio said that a supernova catastrophe involving Eta Carinae was "not very likely" because the energetic jets emanating from the star did not appear to be pointing toward Earth.

"I think we can sleep quietly tonight for Eta Car not extinguishing life on Earth," he said. "However, this particular supernova and all the questions that it brings about will keep us awake for quite a while."