Tiny igloos can generate "micro-tornadoes" in the lab, which could allow scientists to better understand the destructive secrets of real-life twisters-and maybe help predict them.

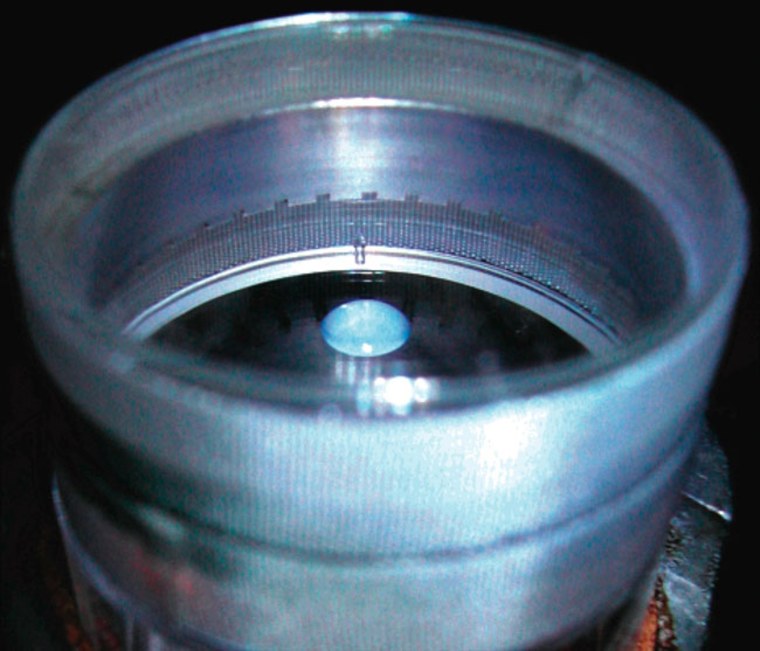

The translucent igloos, made of tiny water droplets and plastic balls, are only millimeters across. As these crystalline domes evaporate on Petri dishes-sometimes taking as long as nearly eight days to finish dissipating-they create micro-tornadoes under their roofs just roughly half the width of a human hair.

Real-life tornadoes are essentially natural engines, where warm, humid air from the ground rises upward into the colder atmosphere, converting heat into mechanical violence in the process. The result-the world's most powerful winds.

The micro-tornadoes formed under conditions identical to ones that spawn real twisters. As the igloos evaporated, they emanated vapor that pooled on the floor. At the same time, the icy domes of the igloos made the air near the roofs colder. As the vapor rose into this cooler air, micro-tornadoes appeared, findings detailed in the June 6 edition of the journal Crystal Growth & Design.

Although scientists understand the basic conditions under which actual tornadoes form, many kinds of twisters exist and the specifics about how they spawn remain mysterious. By tinkering with igloos and mimicking real tornadoes, future research could tease apart how factors such as terrain condition affect tornado growth.

"Knowledge of the relative importance of these factors and of their precise interplay implies the potential to better predict tornadoes," said researcher Andrei Sommer, a senior scientist at the University of Ulm in Germany.

Sommer noted that tornadoes and hurricanes seem to be intensifying worldwide in either number or violence. Shedding light on how they are generated "might help to identify one common element that is responsible for a possible intensification of both events," Sommer told LiveScience.

"It is tempting to say the apparent intensification is from global warming," he added. "However, my feeling is that it might also be something else. Maybe fine dust in the air or urban air pollution is making clouds live longer, allowing for both tornadoes and hurricanes."

Micro-tornadoes made in a tiny igloo

Tiny igloos can generate "micro-tornadoes" in the lab, which could allow scientists to better understand the destructive secrets of real-life twisters-and maybe help predict them.

/ Source: LiveScience