Getting free games is as easy as going on the Internet.

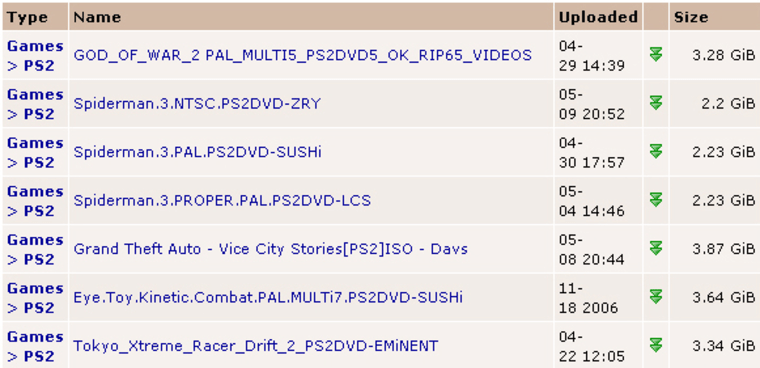

No, I don’t mean casual games and I don’t mean out-of-print stuff. I’m talking about triple-A games — new stuff and old favorites.

Internet “pirate” sites offer “cracked” versions of the shrink-wrapped, copyright-protected software you get at Best Buy. Most of the time, these pirated games are available free of charge. The people who cracked the game’s copy protection and posted it on a peer-to-peer transfer site didn’t do it to turn a profit. They did it just because they could.

Sounds like a gamer’s dream come true, right? Why pay for software when you don’t have to — particularly with retail prices edging up to $60 a pop?

“Because it’s stealing,” says Todd Hollenshead, CEO of id Software. “If you’re unwilling to shoplift in a store, you shouldn’t be downloading illegally pirated versions of games.”

Game piracy has been around since before there was an Internet. And indeed, some pirates are in the business to make money. Go to virtually any market in Southeast Asia and you’ll see rows and rows of commercial games, music and movies available for rock-bottom prices.

Early on, enterprising hackers also figured out how to modify consoles, disabling the copyright protection in the hardware and then reselling the machines with pre-loaded, pirated software. This process is called “modding.”

The Entertainment Software Association estimates that the video game industry loses about $3.5 billion every year due to this kind of hard-goods piracy. But these numbers don’t include the 500-pound gorilla: Internet piracy and peer-to-peer transfers.

“It’s hard to hang a number on losses attributable to Internet piracy,” says Ric Hirsch, the ESA’s senior vice-president for intellectual property enforcement. “But there’s no question that online piracy has impacted commercial performance of PC games and console games.”

That impact has a direct effect on a company’s bottom line — and its ability to make games.

“If the audience of people not playing legitimately is growing faster than audience that is, that’s a bad thing for industry and it’s a bad thing for game fans as well,” says Hollenshead.

These days, a game with all the bells and whistles — cutting-edge tech, deep gameplay, photorealistic graphics — costs a bundle to make. Development periods are longer, teams can number 100 people or more. And the commercial window for the average game is very short, says Hirsch. Not every game is part of a triple-A franchise. Not every company is Electronic Arts. And if your game is competing against a free copy of itself, it could spell real trouble for the people who made it.

That hadn’t occurred to Shane Pittman, a former high-ranking member of Razor 1911, an online game piracy ring.

“It didn’t seem like stealing,” he says. “Physically, I couldn’t see an attachment to anyone.”

In late 2001, Pittman was on the job, working as an IT administrator in Hickory, N.C., when he got the call from the FBI. They were outside the house he shared with his wife, two kids and a cat — and they had a warrant.

The resulting raid on Pittman’s house, which was part of a larger federal sting called Operation Buccaneer, netted seven computers and boxes upon boxes of burned CDs. Pittman pled guilty to conspiracy to commit copyright infringement and served 18 months in a federal prison.

Why would Pittman — husband, father and assistant scoutmaster for his local Boy Scout troop — risk so much for his illegal hobby?

“Because it made me feel important,” he says. “I wasn’t a jock or one of the cool kids, but suddenly, I was the go-to guy. I could do stuff the average Joe couldn’t.”

That feeling of notoriety is addictive, says Hollenshead. “They may be a completely anonymous person without any other claim to fame,” he says. “But within their community, they’re perceived with godlike status.”

And not all of the pirates are good guys with a bad habit, like Pittman. That CD of “Spider Man 3” you bought for $4? It could get to level three and then cut out. That free copy of “Command and Conquer 3” you just downloaded onto your sanitized home PC? It could have a virus.

“Games were one of the first pieces of software to be pirated,” says Ron Teixeira of the National Cyber Security Alliance. “People started taking it seriously when games started making more money than the motion picture industry.”

Teixeria says it’s tough to know how many computers get infected by viruses from pirated games — mainly because no one wants to come forward and admit it. But it makes sense that cracked games, so easy to find on the Internet, would carry the occasional Trojan horse.

“A hacker needs only to find a way to get a malicious program into a computer and use it as a network,” he says.

Even though law enforcement has stepped up the pressure on pirates in recent years — both at a federal and local level — the industry still faces an uphill battle. Much of the pirate trafficking takes place outside of the U.S., in places like Russia and China. And it's tough to get law enforcement there to care much about our copyright and intellectual property laws.

What's more, the copyright protections developers place on CDs can be cracked — and with an army of hackers out there, it’s practically assured that your product will be illegally uploaded to the Internet. From there, it spreads like wildfire, and at that point, there’s little companies can do to stem the tide.

“If you had a piece of software that was broken, you release a patch,” says Hollenshead. “But once your software’s been cracked or hacked, that version propagates faster and faster until it fills up illegitimate distribution channels.”

So why fight it? Maybe game pirate sites have sprouted to fill the same void that music consumers saw in the late 1990s. The void that gave rise to illegal file-sharing on Napster and Kazaa — but ultimately led to iTunes. There’s a business that doesn’t seem to be suffering much from the illegal peer-to-peer music trade.

The game industry will tell you that the typical game is too big to download — and that the average game consumer won’t wait for a 1-gigabyte file to trickle onto their home PC.

But what, then, explains the popularity of Xbox Live and nascent digital distribution sites like Direct2Drive and Steam? Doesn’t the sheer number of BitTorrent sites with thousands of copies of cracked “Quake 4” and “Grand Theft Auto” prove that consumers do want to get their games the same way they’re getting everything else these days?

Maybe that’s not the answer at all, though. Perhaps the answer is much simpler: Pirated games exist because people get a thrill out of cracking games — and because there will always be people who want something for nothing.