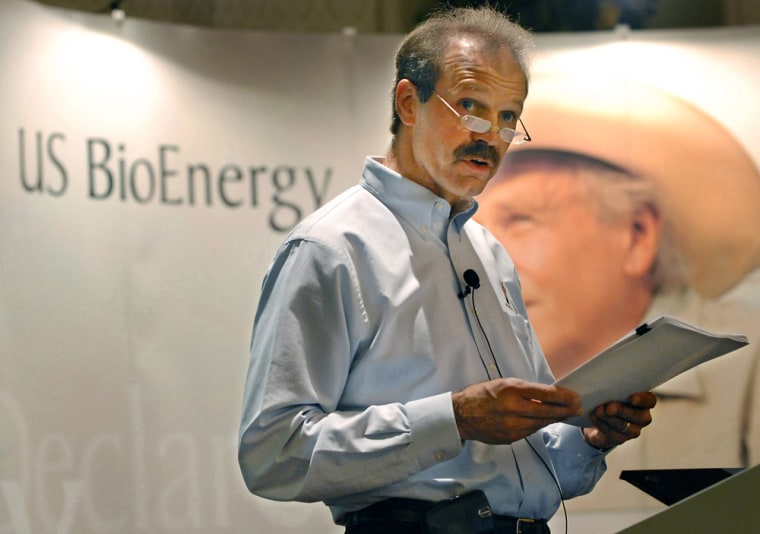

In the 2½ years since Gordon Ommen co-founded US BioEnergy Corp., the company has quietly grown into one of the country’s top ethanol producers, with plans to double in size this year and grow its capacity to 1 billion gallons a year by 2009.

But Ommen knows there are challenges ahead for both his young company and the rapidly growing ethanol industry. Thanks to that fast expansion and some distribution issues, some Wall Street and university analysts predict the ethanol boom is about to stumble on a supply glut and shrinking profit margins.

“It’s going to be a little bit of a bumpy ride, I think, but in the long run we are bullish on renewable fuels and believe that they are going to be a part of our domestic fuel stream for a long time to come,” said Ommen, chairman, president and CEO of Inver Grove Heights, Minn.-based US BioEnergy.

It’s a view shared by Geoff Cooper, who runs ethanol programs for the National Corn Growers Association. He said the industry expects what he called a temporary oversupply for several months, though he hesitated to call it a glut.

Lehman Brothers analysts estimated the surplus at about 1 million gallons per day starting in the second half of 2007. The firm’s report attributed part of that to the ethanol plant construction boom, but said transportation bottlenecks are a bigger problem.

Ethanol is produced mainly in the Midwest and has to be moved to coastal markets by train or truck since pipelines don’t exist, said Michael Waldron, a co-author of the report.

“The supply is coming online and there isn’t really an efficient way to get it to the demand centers on the East and West Coasts,” he said.

Currently, agribusiness conglomerate Archer Daniels Midland Co., of Decatur, Ill., is easily the country’s largest ethanol producer with annual capacity of 1.1 billion gallons, and has expansion plans that will raise that to 1.6 billion gallons.

US BioEnergy, with 300 million gallons of capacity, was No. 1 among the companies that primarily produce ethanol until Brookings, S.D.-based VeraSun Energy Corp. opened a new plant in April that boosted its capacity to 340 million gallons. VeraSun has plants under construction or in development that will boost capacity to 670 million gallons. US BioEnergy is building plants to expand its capacity by as much as 450 million gallons; its goal is 1 billion by 2009.

“We expect the relentless supply of new ethanol production capacity will lead to a 70 percent decline in margins by 2009,” wrote Bank of America analyst Eric K. Brown in a report late last month. The report, “The Ethanol Floodgates Have Opened,” downgraded ratings on several ethanol-related stocks.

Researchers at Iowa State University also raised concerns about profit margins being battered by corn prices that, driven by ethanol, have risen from under $3 per bushel last summer to close to $4 per bushel lately. They say that will make it difficult for ethanol plants to make money. And as the ethanol supply grows, they predict, ethanol prices will drop relative to gasoline unless there’s a change in government policy to encourage more demand for it.

“People who raise equity for ethanol plants don’t like hearing this,” said Bruce Babcock, director of the Center for Agriculture and Rural Development at Iowa State.

Last year the United States produced nearly 5 billion gallons of ethanol and will reach around 7 billion this year, according to the Renewable Fuels Association, the ethanol industry’s main trade group.

The federal renewable fuels standard sets a goal for Americans to burn 4.7 billion gallons of renewable fuels such as ethanol this year, rising to 7.5 billion gallons by 2012. Some states also offer various tax incentives to encourage ethanol use. Some states also have mandates. Minnesota, for example, requires that all gasoline sold in the state be 10 percent ethanol.

Babcock said once production reaches the 9 billion to 10 billion gallon range, the price will have to come down to induce blenders to use more of it than the rules now require, he said.

Ethanol now makes up about 4.5 percent of the nation’s gasoline mix, depending on location. Once that rises to 10 percent — the percentage all cars now sold in the U.S. can use without modifications — Babcock questions where any additional demand would come from. Given that ethanol has about two-thirds the energy content of gasoline, he said, ethanol would have to be priced at two-thirds the price of gasoline to induce a major turn toward E85, an 85 percent ethanol blend that can power flex-fuel vehicles.

“Otherwise no one will fill up with E85,” he said.

The chairman of the National Corn Growers Association, Gerald Tumbleson, shares that concern.

“We call it a ’blend wall,”’ said Tumbleson, who farms near Sherburn in southern Minnesota. “If you hit that blend wall, what’s the value of our product? That’s what makes us nervous.”

Tumbleson said corn growers are hoping to get laws changed to require even greater use of ethanol, such as a 20 percent mandate. He said America’s energy independence is at stake.

The Renewable Fuels Association is downplaying fears of a glut. Matthew Hartwig, a spokesman for the group, said there’s a lot of room for growth before ethanol makes up 10 percent of the market, which would be around 14 billion gallons a year.

“Certainly the market for E85 will continue to grow as Detroit builds more of their new vehicles as E85 vehicles,” and as gas stations install more E85 pumps, he said. Most stations that offer E85 are in the Midwest, though availability is expanding.

Hartwig discounted fears of distribution bottlenecks, expressing optimism that the railroads can handle the volume. The industry increasingly has been using long “unit trains” carrying nothing but ethanol from where it’s made to where it’s needed. Pipelines may finally make economic sense down the road when the industry produces larger volumes of both grain and cellulosic ethanol made from other plant material, he said.

A glut could set the stage for industry consolidation, said Pavel Molchanov, an analyst with Raymond James & Associates. But industry observers said consolidation is not a burning issue right now.

If a shakeout does happen, US BioEnergy may be in acquisition mode, Ommen said. The company picked up five of its operating or planned plants through acquisitions. Most recently, it announced May 31 that it’s acquiring Millenium Ethanol LLC, which is building a plant near Marion, S.D., with a capacity of 100 million gallons per year that’s expected to begin production in the first quarter of 2008.

“There’s going to be bumps in the road,” Ommen said. “Those bumps could produce opportunities for well-positioned companies.”