Weighing in at 150 pounds (70 kilograms) or more, the all-time biggest bird couldn’t just hop into the air and fly away, researchers say.

A team led by Sankar Chatterjee of Texas Tech University used computer programs originally designed for aircraft to analyze the probable flight characteristics of Argentavis magnificens, a giant bird that lived in South America 6 million years ago.

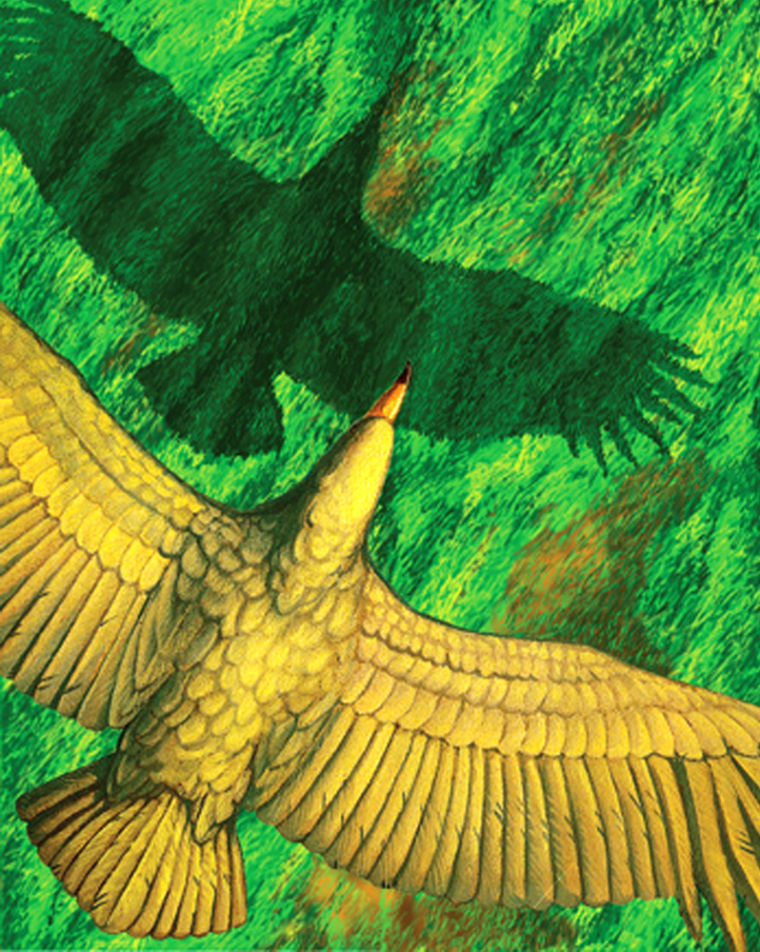

Like today’s condors and other large birds, Argentavis would have had to rely on updrafts to remain in the air.

Doing so, it could have soared for long distances, they conclude in a paper in Tuesday’s edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Remains of Argentavis have been found both in the plains of northern Argentina, called pampas, and also in the foothills of the Andes.

With a wingspan of about 23 feet (7 meters), Argentavis is the largest-known flying bird, the researchers said.

By measuring the size of the bones they determined how large its flight muscles would have been, and calculated that it would not have been capable of takeoff or of sustained flight just by flapping its wings.

“Gliding would not be a problem. It would be the takeoff. That is the main limiting factor,” Chatterjee said in a telephone interview. “In the mountains, takeoff was not a problem, but sooner or later it would come to the plain.”

As far as getting airborne there, Chatterjee suggested the birds could launch from a high point in the foothills. In addition, with a slight headwind and as little as a 10-degree downhill slope they would probably have been able to take off in a running start, the researchers said.

But it looks as if this was just about the size limit for a flying bird, he said.

A steady east wind blowing from the Atlantic Ocean and rising in the foothills of the mountains would have created ideal conditions for soaring flight, in which they estimated the giant hunter could reach 40 mph (64 kilometers per hour).

“Large broad-winged landbirds, such as eagles, buzzards, storks and vultures with slotted wings are masters of thermals and travel cross-country by gliding in circles,” they researchers said.

Thermals are areas of rising warm air and can often be easily determined from a distance because cumulus clouds develop above them when the moisture in that air cools and condenses.

In every culture there are tales of large birds, whether local Indians, Hindus or others, Chatterjee observed.

“Now we can show that they actually existed,” he said, though this bird lived millions of years before humans walked the planet.

And with a skull nearly 2 feet (60 centimeters) long, Argentavis “was catching sizable prey with its formidable beak.”

The research was funded by the National Geographic Society and Texas Tech University.