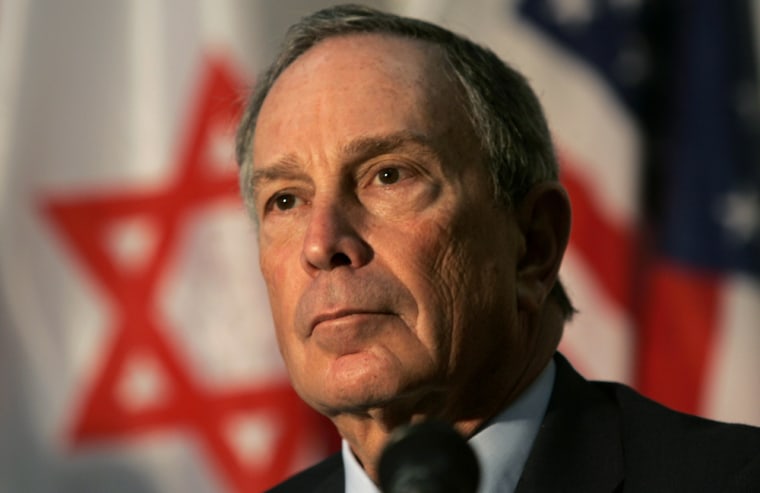

Michael Bloomberg isn’t known here as the Jewish mayor.

In fact, his religion is a non-issue in a city that had its first Jewish chief executive, Abe Beame, three decades ago. The New York Jewish community is so large and active that even non-Jewish mayors take counsel from rabbis. So when Bloomberg won the 2001 mayoral race, Jews saw no significant advantage in having one of their own in City Hall.

But if the billionaire businessman decides to run for the White House, his faith will become much more than an afterthought: He would be on a path toward being elected the first Jewish president of the United States.

“I think it’s a great commentary on American political life when a person who happens to be Jewish is mentioned as a possible presidential candidate,” said Rabbi Joseph Potasnik of the New York Board of Rabbis, who speaks regularly with Bloomberg and has hosted the mayor at a Passover seder and other events.

Bloomberg denies any plans to run, but recently switched from Republican to unaffiliated, clearing the way for a possible independent bid in a field where none of the announced candidates is Jewish.

Still, there is no evidence that Jews will support Bloomberg because of their shared faith.

American Jews vote overwhelmingly Democratic, with a small minority loyal to the Republican Party. Even when Connecticut Sen. Joe Lieberman, an Orthodox Jew and a Democrat at the time, became the first Jewish vice presidential nominee in 2000, there was little change in Jewish backing for the party. Between 1996 and 2000, the proportion of Jews that voted Democratic increased by only 1 percentage point to 79 percent, according to exit polls.

“People thought every Jew in America would run out and vote for Lieberman,” said Rabbi Gary Greenebaum, interreligious affairs director for the American Jewish Committee, an advocacy group based in New York. “But Jews are fairly sophisticated voters. They don’t vote along the lines of, ‘I’ll vote for the Jew because I am one.’ They tend to vote issues. They tend to vote politics.”

Bloomberg would also be competing against two other New Yorkers — Democratic Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton and Republican former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani. Each of those candidates has built strong ties to the Jewish community.

And in a campaign season when Democrats are speaking out as much as Republicans on the importance of faith, the mayor may be at a disadvantage.

‘You are what you are’

Bloomberg, who declined to comment through his spokesman, has said he is not very religious. Other than mentioning that he plans to celebrate a few major Jewish holidays with his family, he almost never discusses his faith. He joined a prominent Upper East Side synagogue, Congregation Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue, which is part of the liberal Reform branch of Judaism, but only occasionally attends worship, Potasnik said.

“Don’t pull out his attendance record” the rabbi joked.

In a 2005 interview with The New York Times, Bloomberg made a rare comment on his religious views. “I believe in Judaism, I was raised a Jew, I’m happy to be one — or proud to be one,” he said. Then he paused and added: “I don’t know if that’s the right word. I don’t know why you should be proud of something. It doesn’t make you any better or worse. You are what you are.”

Bloomberg, 65, had a fairly typical religious upbringing for American Jews of his generation.

He was raised in a kosher home in Medford, Mass., just outside Boston, had a bar mitzvah, and, according to Potasnik, still remembers a few Yiddish words. Jewish leaders who speak with him regularly say they haven’t heard him mention facing anti-Semitism as a child.

‘There’s a comfort level that he has’

After the media mogul earned his fortune, he created an endowment for his hometown synagogue, which was renamed for his parents: Temple Shalom, the William and Charlotte Bloomberg Jewish Community Center of Medford. The congregation belongs to the Conservative movement, which emphasizes traditional observance while allowing some changes that adapt to modern times.

Bloomberg has given millions to Jewish causes in the United States and in Israel. He emphatically supports the Jewish state and has traveled there numerous times.

This past February, he dedicated a $6.5 million emergency rescue service facility in Jerusalem named for his father. On the same visit, he toured the southern Israeli town of Sderot, expressing solidarity with a small community that has been a frequent target of Palestinian rocket fire.

“I think there’s a comfort level that he has with his identification as a member of the Jewish community,” said Rabbi Michael S. Miller, chief executive of the Jewish Community Relations Council of New York. Every year since he was elected, Bloomberg has hosted a reception with kosher food at Gracie Mansion, the city’s official mayoral residence, commemorating the council’s Jewish Heritage New York project.

“He’s an ardently strong supporter of Israel,” Miller said.

However, neither of the mayor’s two daughters celebrated a bat mitzvah, and Bloomberg, who is divorced, officiated at his daughter Emma’s wedding, which was a civil ceremony.

“He’s a fairly assimilated Jew,” Greenebaum said. “I don’t think it will be a big thing.”