The Mona Lisa should hang in a museum, not a subway platform. The Statue of Liberty should stand unvarnished in New York Harbor, not draped with corporate logos.

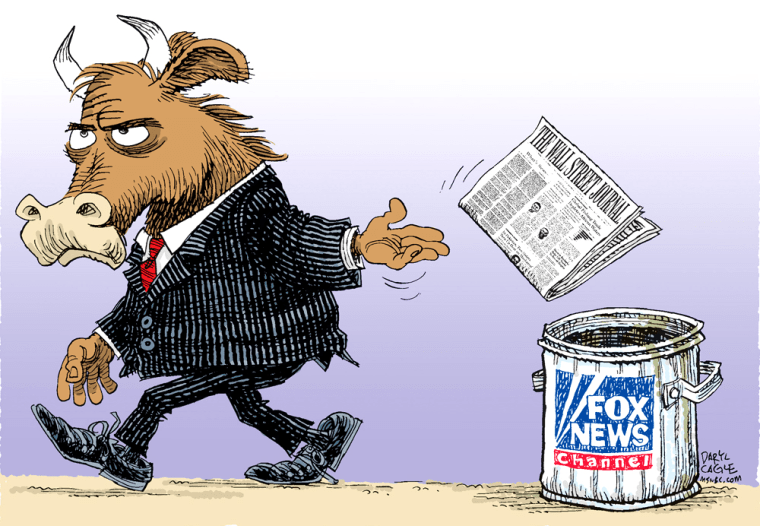

And The Wall Street Journal should be owned by a company dedicated to maintaining its integrity, not one grasping to find content for a yet-to-be-launched cable channel.

Unfortunately, the reality for America's premier business newspaper is quite different. According to reports, the Bancroft family has decided to cash out, accepting a $60-a-share offer for Dow Jones stock from News Corp.'s Rupert Murdoch. Both the Dow Jones board and the News Corp. board are scheduled to meet to approve the pact. Dow Jones will now be merely a division of a massive company — and The Wall Street Journal a relative pipsqueak in revenue compared to, say, "The Simpsons."

It didn't have to be this way. Dow Jones stock was priced at $70 in early 2000 without buyout offers. Since then, The Wall Street Journal Online has added about 600,000 paid subscribers (many big-city dailies don't even have that many customers after generations in business). Though Dow Jones has its troubles like all media companies, its properties aren't bleeding subscribers or advertisers. The Bancrofts can enjoy their big payday, but what they're giving up — stewardship of an American institution — no amount of money can replace.

Though I’ve never worked for News Corp., I was employed by Dow Jones for five years at The Wall Street Journal Online. There, I wrote a column — one that was fortunate enough to appear in print form scores of times in The Wall Street Journal. During that span, I witnessed the workings of a rare news-gathering operation.

Standards are the lifeblood of WSJ and its related properties. Back in 1998, a source called to ask me to attend a World Series game with him at Yankee Stadium. When the request was shared with WSJ.com’s managing editor, it was denied — even if I paid for the ticket — because it was a ticket I was unlikely to be able to procure on my own, thus making me indebted to the source if I accepted it. Along the same lines, I remember being told in a meeting that not only were advertising representatives who sold for WSJ.com on a different floor; we weren't even allowed to know their names. That way, ad reps and their clients could never influence a story.

It is hard to imagine that News Corp. — a juggernaut with more than $25 billion in revenue in 2006 — will keep such ideas in place, considered almost relics in a struggling business. Since Murdoch’s bid was announced, The Wall Street Journal has excelled at covering the story about itself. If bad news erupts about News Corp., will Murdoch dare let reporters investigate the problem and potentially scare off advertisers?

Since the pay at The Wall Street Journal is somewhat paltry compared to other giants such as The New York Times, for many the pride of saying you work for the most-respected newspaper in the U.S. is a currency that can not be measured. I remember headaches there, to be sure — labor negotiations were always contentious, with management routinely offering a 2 percent annual raise and the IAPE union posting angry missives on bulletin boards. Yet even as brickbats were tossed, Dow Jones chairman Peter Kann (a Pulitzer Prize winner) would be seen lunching with reporters or informally chatting with employees he had just met in elevators. And, whatever their pay gripes, when reporters opened the paper with their bylines gracing the pages of a journalistic jewel — illustrated by its unique dot drawings — it all seemed to be worth it at One World Financial Center.

But with News Corp. running the show, the Journal will lose prestige. When News Corp. buys a property, unfortunate changes are afoot. Just like The Wall Street Journal is a trophy in journalism, that’s what the Los Angeles Dodgers were in baseball when News Corp. grabbed them almost a decade ago. A franchise which had enjoyed a run of only three managers in more than 40 years went through two in the first two years of Murdoch’s reign. The pristine, classic uniforms were not good enough — an alternate jersey was added.

Though it may seem strange in a stubborn, dying industry, for newspapers, image is crucial. Consider: The New York Times may add sections, splash color across the pages and change its look in many ways over generations, but its Gothic-like masthead remains sacrosanct; readers wouldn’t consider it The New York Times with modern lettering. The Journal’s stature suffered earlier this year when it shrank its column width, giving the classic broadsheet less heft. Known for publishing pictures of topless girls in his tabloids, Murdoch running The Wall Street Journal is a blow to its stately image.

No one can complain that he will be an uncaring, absentee owner. The problem is, the opposite will be true: The successful Australian tycoon, who owns a slew of television networks, satellite businesses and newspapers, cares deeply about possessing WSJ. Though he will be savvy enough not to do anything radical in the first few months or even years of his ownership, he will, eventually, meddle — this will be his trophy property, and he has strong ideas of what it should look like. Why offer a more than 60 percent premium on the pre-bid stock price if he can't put his stamp on it?

Readers of The Wall Street Journal, take note. The newspaper you've cherished during morning train rides and quiet lunches may end up oddly disfigured — like the Mona Lisa with a mustache.