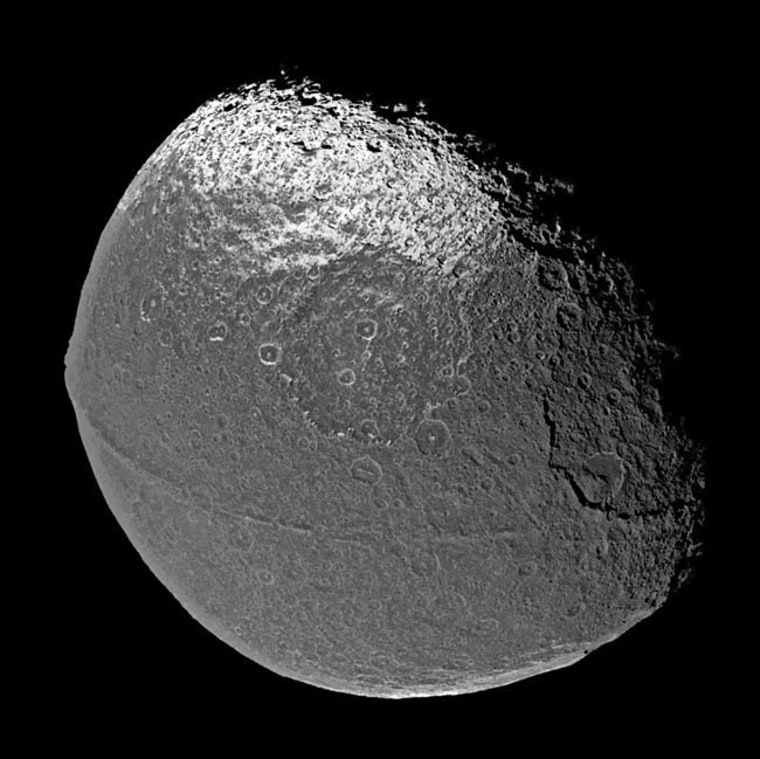

There's a strange moon whizzing around Saturn that's shaped, oddly, like a walnut.

Now astronomers find that Iapetus got its nutty shape from a super-fast spin that was frozen into place early in the solar system's formation.

When the Cassini spacecraft snapped close-ups of Saturn's moons in 2005, it revealed a bulging waistline of rock along the equator of the now slowly spinning Iapetus. Astronomers think this characteristic shape persists because Iapetus was cryogenically frozen in time about 3 billion years ago, during the moon's "teen" years.

"Iapetus spun fast, froze young and left behind a body with lasting curves," said Julie Castillo, a Cassini scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

Unlike any other moon in the solar system, Iapetus (eye-APP-eh-tuss) has retained its immature figure. Running exactly along its midsection, a chain of mountains 808 miles (1,300 kilometers) long and 12 miles (19 kilometers) high adds to the moon's walnut-like appearance.

"You would expect a very fast-spinning moon to have this bulge but not a slow-spinning moon, because the bulge would have been much flatter," said Dennis Matson, another Cassini project scientist at JPL. However, Mason said, "we've modeled how Iapetus formed its big, spin-generated bulge and why its rotation slowed down to its present, nearly 80-day period."

Iapetus originally spun once every five to 16 hours, which was fast enough to buckle its surface at the equator, according to the new model detailed in an upcoming online edition of the journal Icarus.

Scientists think radioactive elements heated the moon's interior to permit the crust to stretch and buckle, yet quickly froze the moon into shape as fuel ran out.

"Iapetus' development literally stopped in its tracks," Castillo said of the 4.564 billion-year-old hunk of rock. In order to slow the young moon down its present once-per-80-days rotational speed, Castillo explained, "its interior had to be much warmer, close to the melting point for water ice."

The finding should help astronomers better understand how the planets and their moon systems formed in the early solar system.

"This is the first direct evidence of the early spin history for a satellite in the outer solar system," Matson said. "It ... broadens our knowledge of the early history of outer planet satellites."