Somewhere deep in cyberspace, where reality blurs into fiction and the living greet the dead, there are ghosts.

They live in a virtual graveyard without tombstones or flowers. They drift among the shadows of the people they used to be, and the pieces they left behind.

Allison Bauer left rainbows: Reds, yellows and blues, festooned across her MySpace profile in a collage of color. Before her corpse was pulled from the depths of an Oregon gorge on May 9, where police say she leapt to her death, she unwittingly wrote her own epitaph.

“I love color, Pure Color in rainbow form, And I love My friends,” the 20-year-old wrote under “Interests” on her profile. “And I love to Love, I care about everyone so much you have no idea.”

Now her page fills a plot on www.MyDeathSpace.com, a Web site that archives the pages of deceased MySpace members.

Behold a community spawned from twin American obsessions: Memorializing the dead and peering into strangers’ lives. Anyone with Internet access can submit a death to the site, which currently lists nearly 2,700 deaths and receives more than 100,000 hits per day.

Interest in the site forced MyDeathSpace offline Sunday and Monday because of a surge in page views.

"The huge amount of traffic has crippled our server for the time being," Patterson wrote in an e-mail. But the site was back online Tuesday.

The tales are mostly those of the very young who died prematurely. Here, death roams cyberspace in all its spectral forms: senseless and indiscriminate, sometimes premeditated, often brutally graphic. It’s also a place where the living — those who knew the deceased and those who didn’t — discuss this world and the next.

There’s a boy, 16, who passed out in the shower and drowned. There’s a 20-year-old whose body was discovered burned to death on a hiking trail; and woman, 21, who overdosed on drugs and was found dead in a portable toilet, authorities say.

Their fates have been sealed, but their spirits remain very much alive — frozen in time, for all the world to see.

Dead person's profile is journey into the past

Scrolling down a dead person’s MySpace profile wall is like journeying into the past. The pages were abandoned hastily, without warning. Most telling is the date of each person’s last log-in.

For 16-year-old Stephanie Wagner, it was Sept. 29, 2006 — a month before she was strangled and stabbed on Halloween night. Her frivolous teenage profile pales against the terrible facts of her murder.

“This site does kind of let you look into the heart of darkness,” says Bob Thompson, professor of television and popular culture at Syracuse University. “We see those kinds of things that we try not to think about, which is how we are all dancing on the edge — how quickly mortality can come in and claim us.”

The human bits scattered carelessly across each profile form a vivid clip of life in motion. It’s a final resting place for the various “selves” people project online: the ironic self, the joyful self, the bitter self, the courageous self.

“I do not fear what the future holds for me,” Navy Hospitalman Geovani Padilla-Aleman, 20, blogged months before he was killed in Iraq. “I will stand and fight. I am not afraid to die.”

Weeks before she stood in the path of a commuter train, Cheryl Lynn Duca pondered mortality in a poem: “over my life i’ve watched people die in front of me. wondering why this happens.”

Many families of the deceased leave the profiles up as memorials. Each profile “wall” — a feature MySpace members typically use to post messages to each other — becomes a conduit for one-way communications with the departed. Days are marked by post-mortem birthday wishes or life updates.

“I made that B in Statistics. and I certainly missed you sittin next to me during the final,” a friend wrote to Casey Hastings, 19, a cheerleader who was killed in a traffic accident.

Some profiles are used as digital billboards to publicize a little-known atrocity. One profile is dedicated to a 3-year-old murder victim.

MyDeathSpace grew out of one person’s morbid curiosity in December 2005, when two teenage daughters were slain by their father. Mike Patterson, 26, a paralegal from San Francisco, tracked down their MySpace pages one day when he was bored. His voyeurism grew into a live journal that later became MyDeathSpace.

“I’d come across these stories where teens would be ending up dead or killing themselves, or killing others,” he says. “And more often than not, when I looked them up on MySpace, they had profiles.”

Permission to use the profiles is not requested from MySpace, which is not affiliated with the site and did not respond to requests for comment on it. MySpace said in a statement it handles deceased members’ pages on a “case-by-case basis” and does not “allow anyone to assume control of a deceased user’s profile.” Profiles can be deleted if that’s requested by family members.

MyDeathSpace matter-of-factly catalogs each death in headline format: “Belford Ramirez (19) died after being stabbed in the neck outside of a Burger King.” Click on the link and you’ll find a detailed description of the fatal attack — an element usually pulled from a news article or blog — his photograph, and a link to his MySpace profile.

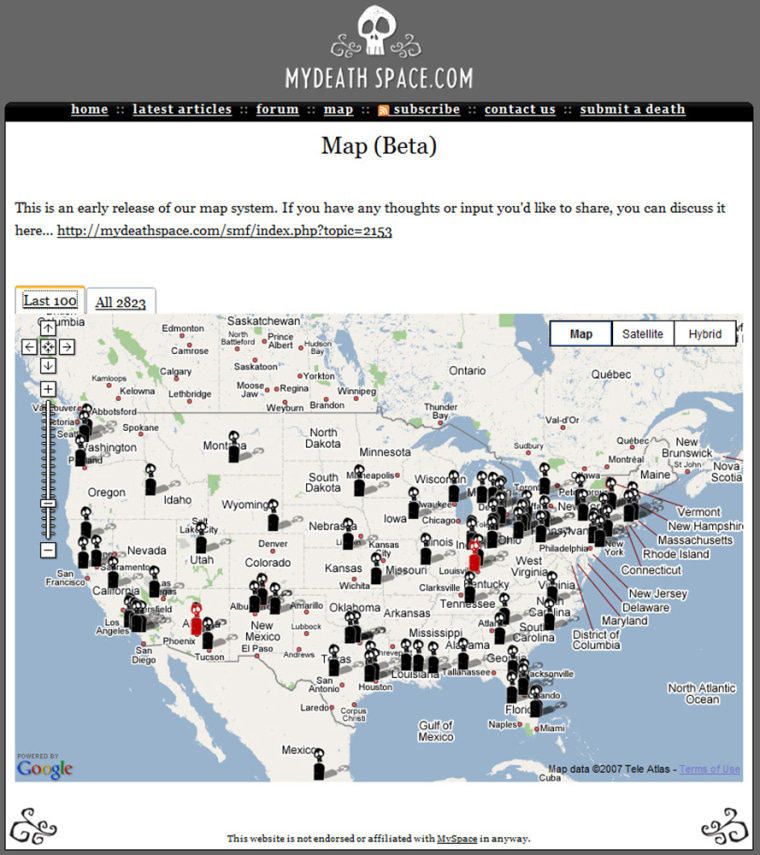

'Death map' charts deaths by location

The site even charts death geographically on a digital “death map” of the continental U.S., using black skulls to signify victims.

In a digital twist on vigilante justice, MyDeathSpace also posts the profiles of homicide victims alongside those of their alleged killers, whose faces loom on the screen like wanted posters.

A 23-year-old accused of pushing a homeless woman into a river appears as a muscular young man in a sleeveless gray shirt, staring coldly into the camera. A 16-year-old girl charged in the shooting death of a 9-year-old shows up striking a sexy bikini-clad pose in her MySpace photo.

Patterson says the alleged killers generate the most discussion threads on the site. “If they’re accused, we’ll put accused,” he says. “We’re not gonna label somebody a murderer who isn’t one.”

But some death submissions slip through the cracks.

There was the case of Christine Hutchinson, a woman from Pittsburgh who was accused of hiding her miscarried fetus in her freezer. She happened to bear the same name as a high school student from Philadelphia — and the latter’s MySpace profile was mistakenly attached to the creepy news story on MyDeathSpace.

Ugly names began filling her inbox: Baby killer, they called her. Murderer. Then death threats.

“They were telling me they hope I die and get stuffed in a freezer, rot in jail, stuff like that,” says the misidentified Hutchinson.

Patterson removed her profile when he was notified of the case of mistaken identity hours later.

But the damage was done. Hutchinson’s face was already out there. She has no plans to sue Patterson, but says she rarely leaves her house alone now, afraid of being attacked.

“It’s got legal liability written all over it, this type of a Web site,” says Internet lawyer John Dozier. Patterson says he has a team to slog through the entries, but he did not elaborate on the process used to verify deaths.

He also refused to disclose profit figures. Ads pop up as you move through the site, and there are fees for certain extras, such as creating personal image galleries in the site’s discussion forums.

In those, paying tribute to the deceased sometimes falls by the wayside, as self-described “death hags” swap whodunit theories, speculate on how victims’ families might feel and muse about the mechanics of violence.

“I’ve never shot a shotgun before, so I don’t understand the physics of it,” writes a user named “wickedly—curious” about a teenage murder-suicide. “Anyone with any insight tell me if it would be possible for 2 people to shoot each other in the heads at the same time?”

MyDeathSpace veers into the dark underbelly of memorializing, says Lisa Takeuchi Cullen, author of “Remember Me: A Lively Tour of the New American Way of Death.”

“Some people rejoice in steamy details,” Cullen says. “The unpleasant thing is that it’s not fictional, it’s not like watching CSI. These aren’t concocted by some scriptwriters in Hollywood who wanted to get a thrill of seeing prostitutes get murdered on the strip.”

For some users, death is just a starting point for discussions of their own lives.

“I just enjoy talking with other members,” Brittany Oliver, 18, of Tucson, Ariz., writes in an e-mail. “I occasionally still read about the deaths, but more so, I enjoy chatting with fellow MDSers about life.”

A subset of newspaper readers who turn first to the obituary page has long existed, explains Thompson, but sites like MyDeathSpace allow such people to interact with each other.

The Internet hosts a garden of other morbid online families. On www.FindADeath.com, users can pore over the latest celebrities who’ve met their Maker. The mortality-conscious can calculate when they might die — based on age and body fat — thanks to www.deathclock.com.

As the traditionally private rites of death and grieving go public, what do families of the dead on sites like MyDeathSpace think?

Army Cpl. Matthew Creed was killed in Baghdad Oct. 22. His MySpace profile keeps watch without him, counting down the time — days, hours, minutes — until he would’ve returned home.

His father, Rick, visits the page from time to time, but he was unaware that it had been archived on MyDeathSpace.

“What MyDeathSpace is doing seems respectful, though at this time I’m not sure what I think about it,” he wrote in an e-mail. What’s most important, he believes, is that the link between his son and this world be preserved.

“We all say, you’re never gone as long as you’re remembered,” Creed says. “And he’s still remembered by everybody.”