After weeks of turmoil in the stock and bond markets, the Federal Reserve Tuesday held tough, offering little indication that it was in the mood to help bail out lenders and investors who have been hit with steep losses.

The central bankers left short-term interest rates unchanged and said in its public comments that the threat of inflation remains uppermost in its policy deliberations.

The statement from the Federal Open Market Committee made note of the ongoing turmoil in the financial markets, the mortgage mess and the tightening of credit. Still, the Fed’s judgment is that those forces don’t pose an immediate threat to the U.S. economy.

"Although the downside risks to growth have increased somewhat, the committee's predominant policy concern remains the risk that inflation will fail to moderate as expected," the central bank said in a statement.

The rate decision extended a year-long policy of leaving short-term interest rates rock steady at 5.25 percent and maintaining a tough stance on inflation.

With billions of dollars worth of paper going up in smoke on the bond market, some on Wall Street had been hoping that Fed policy makers would change its inflation-fighting “bias” in favor of a “neutral” stance — a possible harbinger of lower interest rates to help make credit more available. The Fed acknowledged that it was watching the slumping housing market and fallout from easy-money loans gone bad.

"Financial markets have been volatile in recent weeks, credit conditions have become tighter for some households and businesses, and the housing correction is ongoing," the FOMC said.

"Volatile" is putting it mildly. Investors were paying close attention to what had been expected to be a sleepy summer meeting of the Fed after the stock market's recent violent gyrations — down 300 points one session and up 300 the next. The volatility reflects growing uncertainty over the extent of the damage from risky borrowing and the impact on the economy.

The market continued seesawing Tuesday after the Fed's statement, with the Dow first dropping more than 100 points than jumping more than 100 points before ending the session with a gain of 35 points.

Nobody yet knows how much further the fallout will spread from the housing market downturn, but if banks and investors overcorrect by clamping down on credit, a recession — although considered unlikely — is a possibility.

But with inflation still running a bit hotter than the Fed’s comfort level, and the economy still moving along at a respectable pace, the central bank gave no indication that it plans to cut rates to bail out the sagging housing market or calm or holders of bad loans.

The end of easy money

In recent weeks, the meltdown in the subprime mortgage market has spread to the broader bond market. Home buyers with shaky credit weren’t the only ones affected by the credit bubble that is now unwinding. Hedge funds and other professional money managers snapped up bonds at bargain interest rates, helping fuel the biggest buyout boom since the junk bond mania of the 1980s.

Now, as many of the mortgages supporting those bonds have gone bust, and bankers are backing away from financing new mega-buyouts, money has suddenly gotten a lot more expensive. The rise in market interest rates — and the evaporation of demand for some of these riskier bonds — has left many bond holders with big losses. And the shift in psychology from the days of easy money to fears about credit risk have come faster than even the worst-case scenarios suggested by Wall Street’s computer models.

While home buyers who overborrowed and investors who bought risky bonds are feeling the brunt of the impact, the broader economy has held up relatively well. After sputtering in the first quarter of the year, the Gross Domestic Product expanded by 3.4 percent in the second quarter.

That growth seems to be slowing; job growth in July was a bit weaker than expected and many forecasters are looking for slower growth through the second half. While the housing slump and the shakeout in the credit markets brings the risk of recession, most private economist still say the odds are the economy will avoid a downturn.

The Fed seems to agree — for now — saying “the economy seems likely to continue to expand at a moderate pace over coming quarters."

One reason the economic crystal ball is so cloudy is that prices of some of the riskier bonds at the center of the meltdown have been based on computer models. Now, as the latest cycle of unusually cheap money rapidly comes to a close, the financial markets haven’t figured out where the bottom is.

"It's in the hundreds of billions, perhaps trillions affected," said David Kotok, chief investment officer at Cumberland Advisors. "It has got to be repriced to reflect a market-based pricing system. That is a process in which there will be losses, and the markets know it. They just don't know how big it is and who it hurts the most."

That uncertainty about just how much bad paper is out there is at the heart of the fear gripping the markets. While the Fed has strict guidelines on how banks report their assets, much of the recent easy-money mania was financed with bonds sold to money managers and hedge funds that don’t have to report their holdings.

It’s also not clear just how many more loans will go bad. On the mortgage front, some borrowers who are delinquent on their loans may be able to negotiate new terms to avoid default. Some announced private equity buyouts, meanwhile, may not be able to get the financing that looked like a sure thing just a few weeks ago.

"Banks have a serious question; they have to make a judgment call," said Dan Primack, editor of the Thomson Financials Private Equity HUB Web site. "Either we stick with these deals which we think are bad deals from our perspective, the bank's perspective, or bail on them." Canceling deals would hurt a bank's credibility for future financings, said Primack.

Ironically, the current market crisis is the result, in part, of an extended period of financial stability engineered by the Fed. That may have prompted lenders and investors to “underprice” the risk of lending. Mortgage brokers overlooked borrowers' shaky credit histories. Wall Street snapped up hundreds of billions in bonds, at low interest rates, to back an explosion of private equity buyouts.

Greenspan's example comparisons

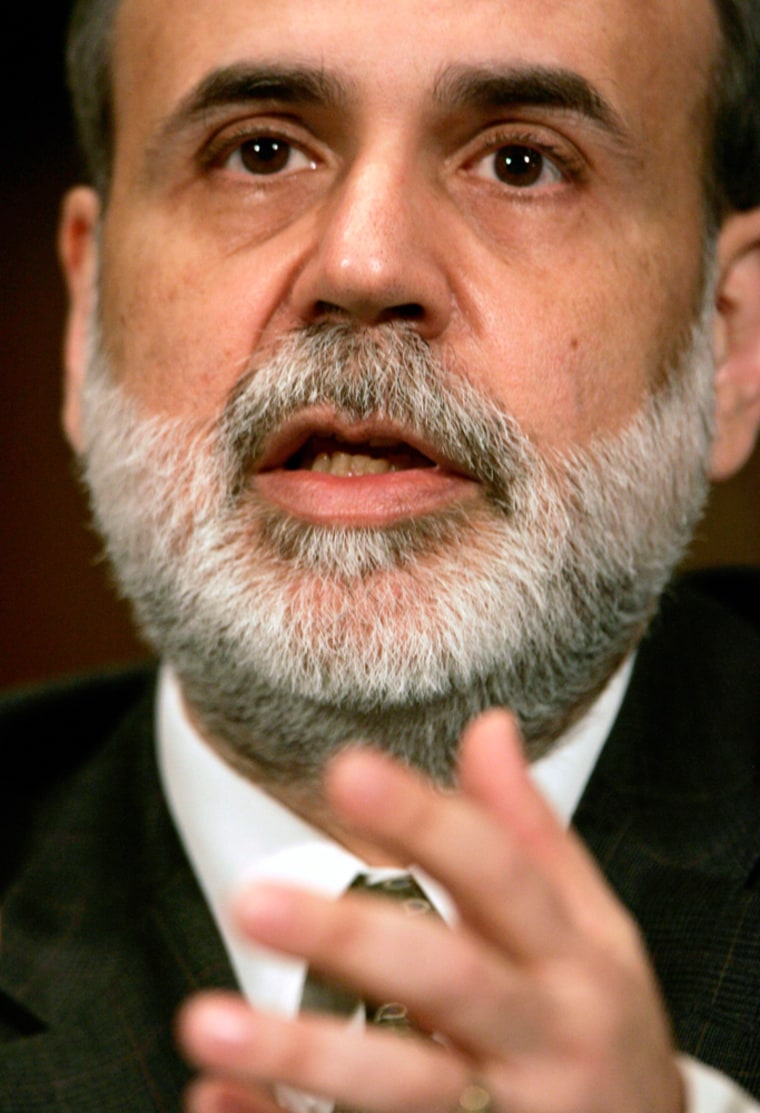

The Fed’s response to the market's turmoil has drawn comparisons between Bernanke and his predecessor, Alan Greenspan, who became Fed chief just a few months before the stock market crashed in October 1987.

Greenspan was praised for helping the market stabilize by announcing the Fed would make available as much money as needed to keep the markets from seizing up.

The current slow-motion collapse of the bond market presents the Bernanke Fed with a tougher call. For one thing, the known losses haven’t yet approached the magnitude of the Crash of ’87. For another, if the Fed moves to make money cheaper by cutting rates, the cycle of easy-money lending — with investors ignoring credit risks — could start all over again.

On the other hand, if lenders and investors get too cautious, and money gets too tight, the economy could slip into a recession. Despite the recent heavy losses on Wall Street, that spillover to the wider economy hasn't happened, according to Stuart Hoffman, chief economist for PNC Financial Services Group.

"The Fed's mission is not to protect the vested interests of Wall Street," he said. "It's to protect the vested interests of the American economy. So I think the Fed got it right."

Tuesday's decision also signaled to Wall Street that Bernanke may be slower than his predecessor to open up the money taps in times of financial crisis.

"I think Bernanke has a much longer view of things (than Greenspan)," said John Silvia, chief economist at Wachovia Securities. "He's not going to react as quickly" as Greenspan did to crises.

An informal survey of roughly 50 economists by CNBC confirms that view. The survey found that the group thinks Bernanke is less likely to ride to the rescue of the financial markets than his predecessor. About two-thirds said he’s less likely to cut rates; a third said the odds of such intervention are about the same.

But a lot depends on how quickly the markets stabilize — and how much collateral damage hits the economy. If the bond market doesn't find its footing, and market psychology shifts to panic-mode, the Fed may have no choice but to step in and put the fires out.

"(Bernanke) understands the dynamics," said Robert Barbera, chief economist at ITG. "But you can be a war theorist and never have hit the beaches on D-Day. He has now changed from someone with an academic interest in this to having to respond to it."