It's still beyond the reach of science to predict exactly when an earthquake will strike, but Japan will soon get the next-best thing — televised warnings that come before anyone feels the ground shake.

Japan's Meteorological Agency and national broadcaster are teaming up to alert the public of earthquakes as much as 30 seconds before they hit, or at least before they can bring their full force down on populated areas.

The system — the first of its kind in the world — does not predict quakes, but officials say it can give people enough time to get away from windows that could shatter, or to turn off ovens and prevent fires from razing homes.

And in one of the world's most earthquake-prone countries, every second counts.

"If we can give people enough time to take even a few steps to protect themselves before the shaking starts, it could help reduce injuries and damage," said agency spokesman Makoto Saito.

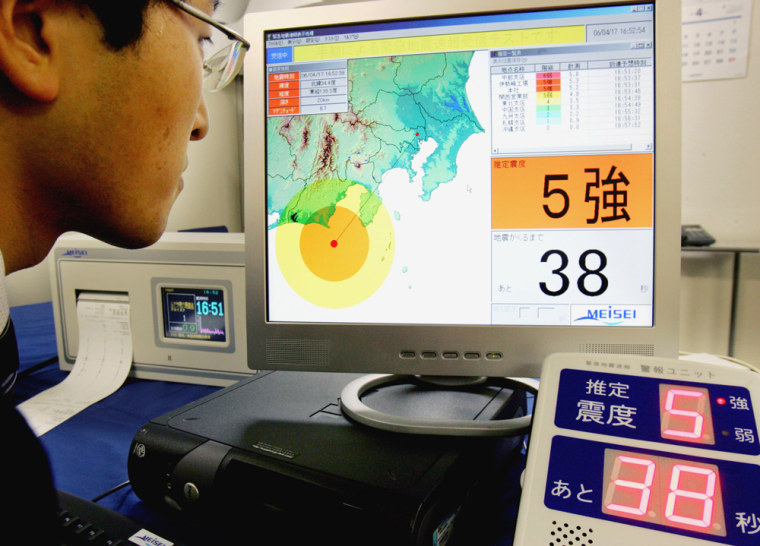

The warnings, to begin in October, will be based on data provided by the Meteorological Agency, which maintains a network of sensors deep underground that estimate the intensity of a quake as soon as the ground ruptures.

Alarms can go out before the shaking starts because there is a lag between the time it takes for different seismic waves to travel to the surface.

Japan, which sits atop four tectonic plates, has been hit by 83 earthquakes strong enough to cause injury since March 1996, including one last month that killed 11 people and caused a fire and small radiation leak at a nuclear power plant.

The warning system works by detecting primary waves, which spread from the epicenter of a quake and travel faster than the destructive shear waves. When waves of a certain intensity are detected, the alarms are set off. The national broadcaster, NHK, will relay them almost instantaneously to its television and radio audiences.

The agency started issuing warnings last August to more than 500 organizations such as power companies and train operators.

The system is not perfect.

Lightning or other interference can cause false alarms, for example, and early warning won't work for areas directly above the ruptured fault because the two waves would be nearly simultaneous. And residents would have to be watching TV or listening to the radio to get an alert.

Still, the agency says the system helped it issue a tsunami alert for a magnitude-6.9 earthquake in northern Japan this March two minutes faster than its old early warning system would have. The agency also was able to put out a warning ahead of last month's magnitude-6.8 quake.

How the public will react has been a concern.

"Chaos and injuries could result, for example, if an urgent earthquake warning is sent to a facility with large numbers of customers and a crush forms at the exits as people rush to get out," a meteorological agency study group said in a report last year.

The warnings, it was decided, must come with explanations of what people should do _ stop cars and elevators, get away from things that can fall and, most of all, protect their heads.

"We realized the warnings won't work if confusion is the result," said Saito. "The public needs to be educated about how and how not to react."

Since early last month, NHK has begun preparing Japan for the alerts, carrying promotional spots accompanied by skits that show how to respond.

Officials say the system may serve as a model for others.

"A lot of the injuries in an earthquake come from secondary damage, like fires started from open gas lines," said Barry Drummond, who oversees seismic monitoring for Geoscience Australia. "If you've got enough time to shut the gas valve, you're that much further ahead."

Small-scale warning systems exist in parts of Mexico, Taiwan and Turkey. In the United States, commercially available, battery-powered seismic gadgets can warn a limited region, while seismologists at the University of California at Berkeley are working on a system inspired in part by Japan's.

"The implementation in Japan is most important to us as a test of the concept," said Richard Allen, who heads the group. "We are particularly interested to see how the public react to the information and (who) starts to make use of the information and how."

Mike Blanpeid, a Virginia-based geophysicist at the U.S. Geological Survey, said the USGS would also be watching Japan's new program closely as they evaluate what kind of investments are required to improve warning systems in the United States.

Blanpeid said Japan's dense network of seismometers, combined with a system that rapidly delivers seismic information to the surface, would make their early warning program particularly effective.

"You can do a lot if you know an earthquake is coming in less than a minute," said Blanpeid.

Associated Press writer Lily Hindy in New York contributed to this report.