In September 1968, Hillary Diane Rodham, role model and student government president, was addressing Wellesley College freshmen girls — back when they were still called “girls” — about methods of protest. It was a hot topic in that overheated year of what she termed “confrontation politics from Chicago to Czechoslovakia.”

“Dynamism is a function of change,” Ms. Rodham said in her speech. “On some campuses, change is effected through nonviolent or even violent means. Although we too have had our demonstrations, change here is usually a product of discussion in the decision-making process.”

Her handwritten remarks — on file in the Wellesley archives — abound with abbreviations, crossed-out sentences and scrawled reinsertions, as if composed in a hurry. Yet Ms. Rodham’s words are neatly contained between tight margins. She took care to stay within the lines, even when they were moving so far and fast in 1968. While student leaders at some campuses went to the barricades, Ms. Rodham was attending teach-ins, leading panel discussions and joining steering committees. She preferred her “confrontation politics” cooler.

“She was not an antiwar radical trying to create a mass movement,” said Ellen DuBois, who, with Ms. Rodham, was an organizer of a student strike that April. “She was very much committed to working within the political system. From a student activist perspective, there was a significant difference.”

As the nation boiled over Vietnam, civil rights and the slayings of two charismatic leaders, Ms. Rodham was completing a sweeping intellectual, political and stylistic shift. She came to Wellesley as an 18-year-old Republican, a copy of Barry Goldwater’s right-wing treatise, “The Conscience of a Conservative,” on the shelf of her freshman dorm room. She would leave as an antiwar Democrat whose public rebuke of a Republican senator in a graduation speech won her notice in Life magazine as a voice for her generation.

‘A sense of tremendous change’

Hillary Rodham Clinton’s course was set, in large part, during the supercharged year of 1968. “There was a sense of tremendous change, internationally and here at home which impacted greatly how I thought about things,” Mrs. Clinton said in a telephone interview about that period, which encompassed the second half of her junior and first half of her senior years.

It was a time at once disorienting and clarifying, a period that would reinforce the future senator and presidential candidate’s suspicion of “emotional politics” while stoking her frustration with what she considered the passivity of her classmates.

Her political itinerary that year resembles a frenzied travelogue of youthful contradiction. She might have been the only 20-year-old in America who worked on the antiwar presidential campaign of Senator Eugene McCarthy in New Hampshire that winter and for the hawkish Republican congressman Melvin Laird in Washington that summer.

She attended both the Republican National Convention in Miami (bunking at the Fontainebleu Hotel, ordering room service for the first time — cereal and a daintily wrapped peach) and the Democratic donnybrook in Chicago (smelling tear gas at Grant Park, watching a toilet fly out the window of the Hilton hotel).

The day after the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was slain, she joined a demonstration in Post Office Square in Boston, returning to campus wearing a black armband.

“People become experiences,” Ms. Rodham wrote about all the ferment in a Feb. 23 letter to John Peavoy, a friend from high school. She added later, “The whole society is brittle.”

Looking back, it is easy to see that ambitious political science major in the first lady, United States senator and, now, presidential candidate she would become. She campaigned meticulously in student elections, going door to door and dorm to dorm. She wrote thank-you notes to professors who helped her.

In the bustle of her excursions, she showed the zeal of an emerging political junkie. And, while outspoken and often blunt, Ms. Rodham was hardly a bomb-thrower. She was, then as now, dedicated to cerebral policy debates, government process and carefully calibrated positions.

“Her opinions are mature and responsible, rather than emotional and one-sided,” Alan Schechter, a political science professor at Wellesley, wrote in a law school recommendation that year for Ms. Rodham.

A Goldwater Girl

Ms. Rodham had arrived at Wellesley in the fall of 1965, a decorated Girl Scout and teacher’s pet from a Republican household in the Chicago suburb of Park Ridge, Ill. She had distributed leaflets for Mr. Goldwater’s presidential campaign the previous fall and was determined to rise quickly through the moribund ranks of Wellesley’s Young Republicans chapter.

As a go-getter freshman, Ms. Rodham was elected president of the group, dutifully recruiting students to help Massachusetts candidates including Edward Brooke, the future United States senator whom she would chastise in a 1969 commencement speech as being out of touch with the concerns of the new graduates.

In 1966, her public words were less audacious. “The girl who doesn’t want to go out and shake hands can type letters or do general office work,” Ms. Rodham told The Wellesley News in an appeal for Republican volunteers. Soon, though, Ms. Rodham’s views began veering leftward. She became opposed to the Vietnam War, putting her increasingly in conflict with her conservative father, Hugh Rodham.

“My opinions on most human conditions are being liberalized,” Ms. Rodham wrote in 1965 to Don Jones, a progressive Methodist minister from back home who had influenced her thinking.

“The combination of bleeding heart liberal and mental conservative is the inevitable conclusion one arrives at after following and pondering political events,” she wrote.

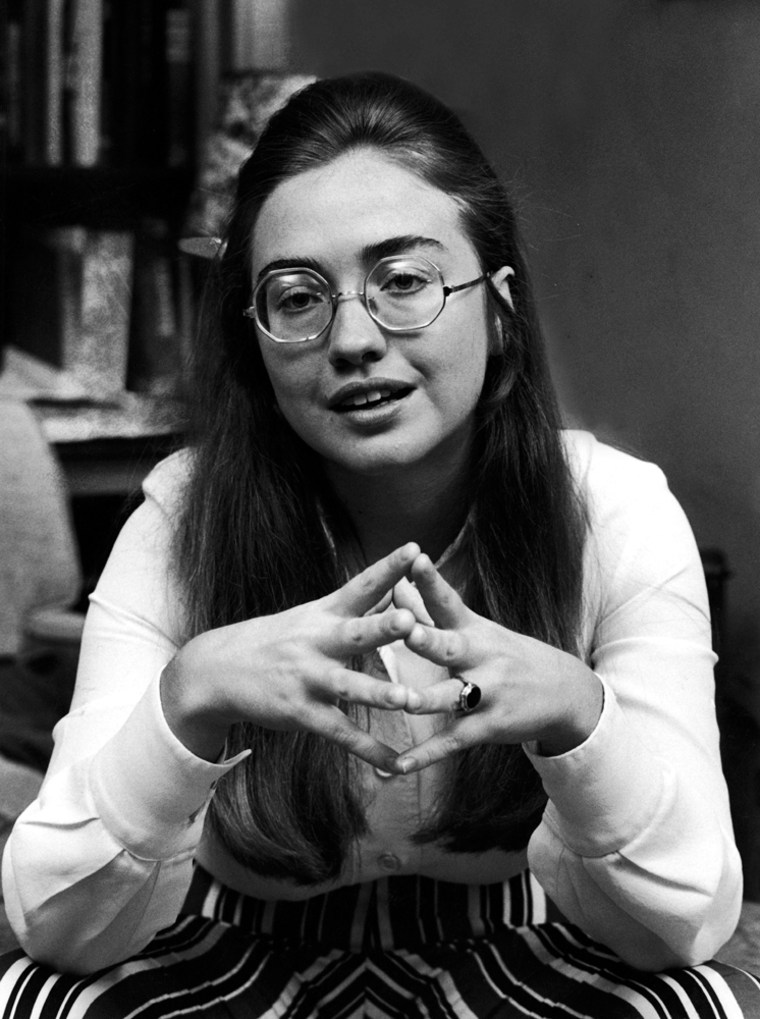

Around campus, Ms. Rodham wore industrial-thick glasses and a uniform of the times — clunky boots, ratty jeans, a Navy blue pea coat and a succession of turtlenecks, sweater vests and work shirts. (“I look like hell and I could care less” she wrote to Mr. Peavoy.) She was prone to capricious fashion choices. A suitemate, Connie Hoenk Shapiro, recalled asking why she had bought a particularly dreadful pair of muddy-colored shoes (with clunky 2-inch heels and a square toe) and Ms. Rodham explaining, “I felt sorry for them and wanted to give them a home.”

Friends say she had a playful streak, was game for road trips to Vermont and Cape Cod, and liked to call people by goofy nicknames. “She would sometimes refer to herself in the third person as “the Hill,” or “the Hill woman,” said her Wellesley classmate Nancy Pietrafesa, whose childhood moniker, Peach, sometimes became Peacharoo or Peacharooni in Hill-speak.

Unlike many of her peers, she never experimented with illegal drugs, Mrs. Clinton said. She embraced collegiate social rituals, attending mixers, showing up to Harvard football games (often with a book, a friend recalls) and planning a strawberries-and-cream bridal shower atop the Wellesley Bell Tower for a roommate, Johanna Branson.

Still, she was something of a sponge for all the angst and argument engulfing her generation. Ms. Shapiro recalled going to do errands one afternoon when Ms. Rodham handed her an unopened bottle of perfume she had bought and asked her to return it to the store.

“I asked why,” Ms. Shapiro recalled. “Her answer was that it was an extravagance she felt guilty about indulging in when there was so much poverty around us. We were increasingly sensitive to issues of what we now call white privilege. ”

When Dr. King was killed on the balcony of a Memphis motel on April 4, 1968, Ms. Rodham was devastated. “I can’t take it anymore,” she screamed after learning the news, her friends recalled. Crying, Ms. Rodham stormed into her dormitory room and hurled her book bag against the wall. Later, she made a telephone call to a close friend, Karen Williamson, the head of the black student organization on campus, to offer sympathy.

Ms. Rodham, who met Dr. King after a speech in Chicago in 1962, had admired his methodical approach to social change, favoring it over what she considered the excessively combative methods of groups like the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, or S.N.C.C., pronounced snick.

“Just because a person cannot approve of snicks’ attitude toward civil disobedience does not mean he wishes to maintain the racial status quo,” Ms. Rodham wrote as a freshman to Mr. Jones, the Methodist minister.

After Dr. King’s assassination provoked riots in cities and unrest on campuses, Ms. Rodham worried that protesters would shut down Wellesley (not constructive). She helped organize a two-day strike (more pragmatic) and worked closely with Wellesley’s few black students (only 6 in her class of 401) in reaching moderate, achievable change — such as recruiting more black students and hiring black professors (there had been none). Eschewing megaphones and sit-ins, she organized meetings, lectures and seminars, designed to be educational.

“I was rooted in a political approach that understood that you can’t just take to the streets and make change in America,” Mrs. Clinton said in an interview. “You can’t just give a speech and expect people to fall down and agree with you.”

‘A sense of disorder’

Even so, the killing of Dr. King created “a sense of disorder that was both unsettling and catalyzing” to Ms. Rodham, recalled Mr. Schechter, the political science professor and a mentor to her. Friends observed that she was less restrained and less deferential after Dr. King’s death.

At a panel discussion for a group of Wellesley alumni in mid-April, Mrs. Clinton bemoaned the “large gray mass” of uninvolved students. At another meeting, she argued with an economics professor who suggested that the strike take place on a weekend.

“I’ll give up my date Saturday night, Mr. Goldman, but I don’t think that’s the point,” Ms. Rodham told the professor, Marshall Goldman, according to the April 25, 1968, Wellesley News. “Individual consciences are fine but individual consciences have to be made manifest. Why do these attitudes have to be limited to two days?”

Ms. Rodham had traveled to New Hampshire several times that winter to volunteer for Mr. McCarthy, the Minnesota Democrat challenging President Lyndon B. Johnson for the Democratic nomination. Mr. McCarthy’s message — that the antiwar movement should operate within the system, not on the streets — appealed to Ms. Rodham. The candidate urged his supporters to be respectful, prompting the young activists to cut their hair, shave their beards and be “Clean for Gene.” That summer, Ms. Rodham took to the streets herself, albeit as a safe observer. While home in Park Ridge, she and a friend, Betsy Johnson, kept hearing about all the commotion downtown at the Democratic Convention. They drove Ms. Johnson’s parents’ station wagon into Chicago to view the spectacle.

“We thought we had seen all there was to see in our sheltered neighborhood,” recalled Betsy Johnson Eberling, another former Goldwater Girl. “It was a radicalizing experience for us, to some extent.”

Mrs. Clinton has said repeatedly how “shocked” she was at the brutality she witnessed — protesters throwing rocks, police officers beating protesters — but describes the bedlam with almost scholarly detachment. In her memoir, “Living History,” she recalls spending hours that summer arguing with a friend over the “meaning of revolution and whether our country would face one.” Even if there was a revolution, the two friends concluded, “we would never participate.”

Keeping a toe in the G.O.P.

For all her leftward movement, Ms. Rodham still kept a toe in the Republican Party, working as an intern in Washington that summer. Mr. Schechter, who supervised the Wellesley internship program, sent her to work for the House Republican Conference, then headed by Mr. Laird, the Wisconsin congressman who would later become President Richard Nixon’s defense secretary. “My adviser said, ‘I’m still going to assign you to the Republicans because I want you to understand completely what your own transformation represents,” Mrs. Clinton recalled of Mr. Schechter.

“I remember her being very bright, very aggressive and not very Republican,” said Ed Feulner, who managed the summer interns in the office and now heads the Heritage Foundation, a conservative research group.

Ever diligent, Ms. Rodham did “a fine job,” said Mr. Laird, citing a “very thorough and well-researched” speech she wrote on the financing of the Vietnam War. At the end of the internship, Ms. Rodham proudly posed for a photo with House Republican leaders, including Representative Gerald R. Ford of Michigan. The photo hung in her father’s bedroom when he died in 1993.

Along with other interns, Ms. Rodham was invited by Representative Charles Goodell, a moderate New York Republican, to help Gov. Nelson Rockefeller’s last-ditch campaign to defeat Mr. Nixon for the Republican nomination. At the party’s convention in Miami, she met Frank Sinatra, shared an elevator with John Wayne and decided to leave the Republican Party for good. “She was particularly furious at how she felt Rockefeller had been trashed by the Nixon people,” Mr. Schechter said.

“I’m done with this, absolutely,” Mrs. Clinton recalled thinking upon hearing Mr. Nixon’s acceptance speech. She characterized the Republicanism of her youth as one of fiscal conservatism and social moderation, and at odds with what she viewed as the intolerance of Miami.

“All of a sudden you get all these veiled messages, frankly, that were racist,” Mrs. Clinton said of the convention. “I may not have been able to explain it, but I could feel it.”

Back at Wellesley that fall, Ms. Rodham immersed herself in campus matters. She reveled in her role as student government president, which offered both the visibility and social validation she craved. (“I think I enjoy winning elections as a tangible proof of respect and liking,” she wrote to Mr. Peavoy.)

She won the post in the spring, after campaigning for two weeks “spouting the usual platitudes,” as she said in her letter. When she learned of her victory, she was stunned and thrilled. “Can you believe this?” she said over and over, recalled a professor, Steve London, who received a thank-you note from Ms. Rodham soon after her election. “I think it was a form letter that went out to all the faculty,” Mr. London said.

As the year was ending , Ms. Rodham was working on a 92-page honors dissertation on Saul Alinsky, the antipoverty crusader and community activist, whom she described (quoting from The Economist) as “that rare specimen, the successful radical.”

Power and activism

Beyond Mr. Alinsky, the treatise yields insights about its author. Gaining power, Ms. Rodham asserted, was at the core of effective activism. It “is the very essence of life, the dynamo of life,” she wrote, quoting Mr. Alinsky.

Ms. Rodham endorsed Mr. Alinsky’s central critique of government antipoverty programs — that they tended to be too top-down and removed from the wishes of individuals.

But the student leader split with Mr. Alinsky over a central point. He vowed to “rub raw the sores of discontent” and compel action through agitation. This, she believed, ran counter to the notion of change within the system.

Typically, the paper, which received an A, was neatly typed, exhaustively footnoted and even included a page of acknowledgments. “Although I have no “loving wife” to thank for keeping the children away while I wrote,” Ms. Rodham said, “I do have many friends and teachers who have contributed to the process.”

In a listing of primary sources, Ms. Rodham reported that she met three times with Mr. Alinsky and that he offered her a job. “After a year trying to make sense of his inconsistency,” she wrote, explaining her demurral, “I need three years of legal rigor.”