Enormous monsters scuttle across the screen in the movie "Alien," devouring humans with a second, saliva-dripping set of jaws thrust from the back of their throats. Although the creatures are contrived, a new study shows that moray eels use such a set of jaws to eat.

The discovery shows that morays use the second, hidden set of jaws to drag unsuspecting meals to their doom — a behavior unique among the eels' bony fish relatives, who suck in meals like vacuum cleaners.

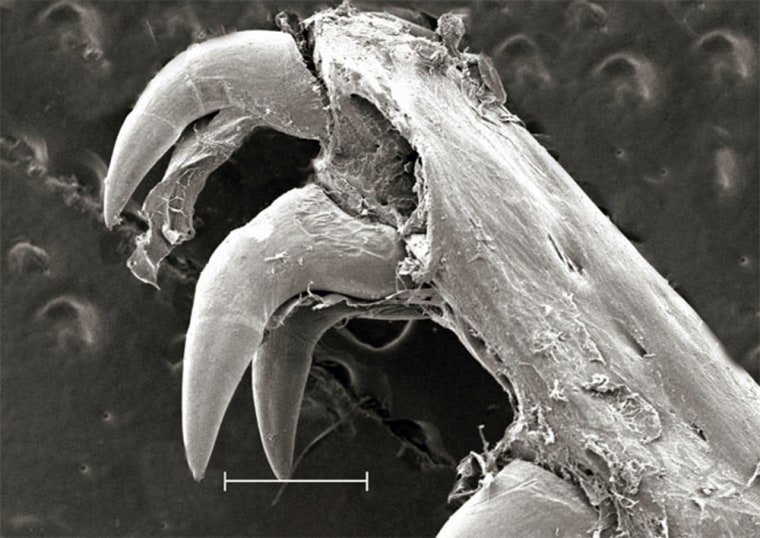

New high-speed videos show a set of pharyngeal jaws, located in the back of an eel's throat, springing into action.

"We had no idea how moray eels were able to swallow prey before this study," said Rita Mehta, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California in Davis.

Predatory mammals attack and munch on prey with a single set of jaws. Most fish, on the other hand, clamp down on their meals with one set of jaws and then suck it back to pharyngeal jaws for further processing.

But moray eels' pharyngeal jaws are unlike those of any other bony fish.

"They have the most extreme mobility of any pharyngeal jaws ever documented, just these wonderful forceps that grab prey," Mehta said.

In a lightning-fast swimming maneuver, slender-bodied moray eels clamp down on their prey with a forward set of toothy jaws. In almost the same instant, slender muscles sling an inner set of grapple-like jaws onto the prey — which can be nearly as wide as the eel itself—and pull it towards the animal's gut.

Jokingly, Mehta noted that the mechanism was oddly similar to that seen in creatures from the movie "Alien." "One person I showed it to even asked me if there wasn't a second eel inside," she said.

While the finding pertains to just a single creature so far, Mehta explained that it may change how other scientists view and study underwater evolution.

"Feeding is an extremely important component to survival, so it's one way that an organism can really set itself apart from all other creatures it has to compete with. We now know we can be looking for aquatic feeding other than suction," Mehta said. "The moray shows us that the world's oceans may be more behaviorally diverse than we previously thought."

Mehta and her colleague's findings will be detailed in the Sept. 6 issue of the journal Nature.