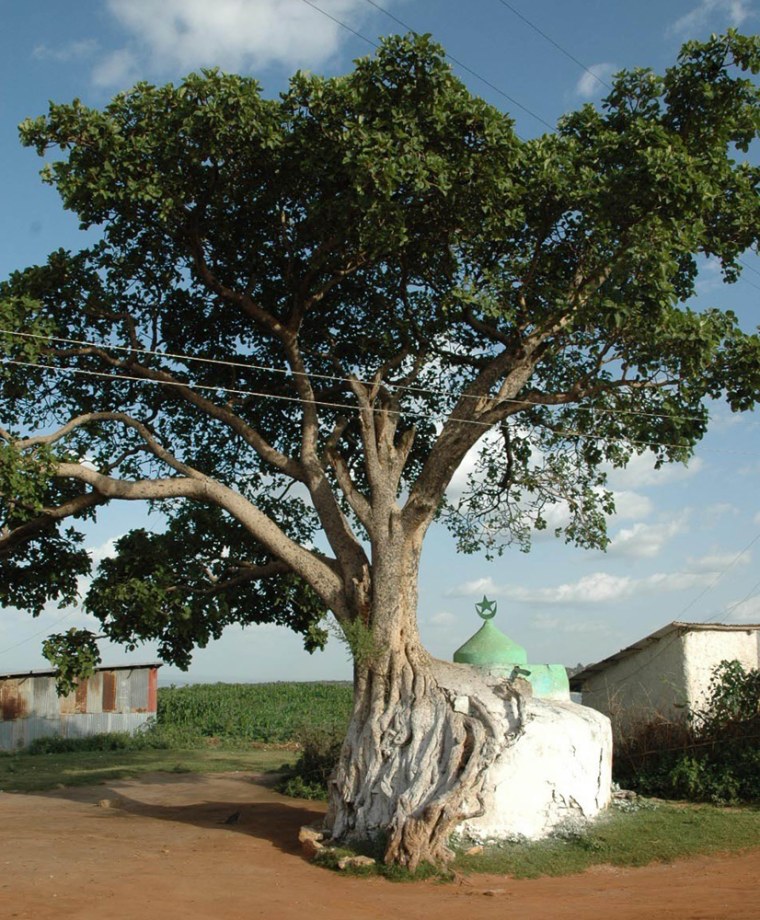

For 1,000 years, this city on a hilltop has been a center of Islamic faith in the Horn of Africa, with a forbidding, 13-foot wall surrounding ancient mosques and serpentine alleyways.

Now, Harar leaders are hoping it can become a center of tourism as well.

"The future of Harar is tourist attraction," said regional president Murad Abdulhadi.

Harar was named a UNESCO World Heritage site last year, joining some of the world's top landmarks such as the Grand Canyon in the United States, the Great Wall of China and the Acropolis in Greece.

It is also the fourth holiest city in Islam — behind Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem. And some consider Harar the birthplace of coffee. Its aroma wafts through the cool air of the Ethiopian highlands.

Some of Harar's attractions defy easy explanation, such as the old man who hand-feeds some 50 hyenas every night, treating them like obedient kittens.

But the city, which lies some 250 miles from the capital, Addis Ababa, lacks modern amenities and suffers from a chronic water shortage. With only a handful of hotels and the nearest airport more than an hour's drive away, moving Harar into the future is an ambitious plan.

Abdulnasser Idriss, who heads Harar's tourism department, acknowledges the city faces "a big problem" in accommodating any more than the 4,500 tourists who come here each year.

In order to speed development, the regional government has given a 10-year tax break to anyone interested in building tourist facilities. Federal officials also say they are planning to make Harar and its neighboring city, Dire Dawa, part of an advertising campaign to lure tourists from neighboring Djibouti.

Other incentives include land awards and free technical advice on construction projects, said Federal Minister of Culture and Tourism Mohamoud Dirir.

Ethiopian officials would not say how much has been invested so far, but construction is everywhere: unfinished hotels and restaurants dot the road leading into the main part of the city.

Oil baron Sheik Mohammed Alamoudi, believed to have invested more than $1 billion in his native country, has sent a team to Harar at the request of regional officials to investigate potential to build the city's first luxury hotel.

"Things are coming up," said Mohamoud, the culture and tourism minister. "We are very optimistic."

The city is also planning a $34.5 million water project that will increase Harar's available water supply more than sevenfold. Each resident in Harar now gets five gallons of water per day.

But what Harar lacks in modern amenities it more than compensates for in ancient wonders: nearly 100 old mosques, fortress-style walls, alleyways filled with ancient homes.

Harar is also the site of the former home of French poet Arthur Rimbaud, who lived there in the late 1800s. The airy, colorful house is now an art gallery showing modern photography and Ethiopian crafts.

Abdurahman Ibrahim, 38, who lived in Harar as a child but recently returned for a visit, said the city has become much more alluring to tourists.

"Everything has changed," said the Toronto, Ontario, resident. "Most of the things for the better. The city has grown so much. The road is better. The electricity is better. The water is better."

Still, as Harar moves further into the modern world, many locals say they're proud of the past.

"The basic thing is we want to protect this culture, to keep it as it is for the next generation," said Zeydan Bekri, a lifelong Harari who lobbied the United Nations for five years to get the UNESCO designation.

Holy Ethiopian city aims to become tourist hub

For 1,000 years, this city on a hilltop has been a center of Islamic faith in the Horn of Africa, with a forbidding, 13-foot wall surrounding ancient mosques and serpentine alleyways.

/ Source: The Associated Press