A nine-day mission that began Monday in the world's only permanent working undersea laboratory is like living in a fishbowl in more ways than one: Anyone with an Internet connection can watch the researchers work and hang out 60 feet (18 meters) below the surface.

Six "aquanauts" studying changes along a coral reef will work, sleep and eat at Aquarius Reef Base, on the Atlantic Ocean floor about nine miles southeast of Key Largo in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. It's the first time students and others will get such an extensive real-time view of the underwater life surrounding the 21-year-old lab.

The team, hoping to raise interest in science and the oceans, is bringing its research to students with undersea classroom sessions and to the public through live Internet video. Feeds are coming from inside and outside Aquarius, and from divers wearing helmets mounted with cameras and audio equipment.

"It would be ideal if all the students we are going to reach on this mission could actually be here, but the truth is most of them will never get that opportunity," said Ellen Prager, chief scientist for Aquarius. "So the best we can do is have them connect and be virtually there."

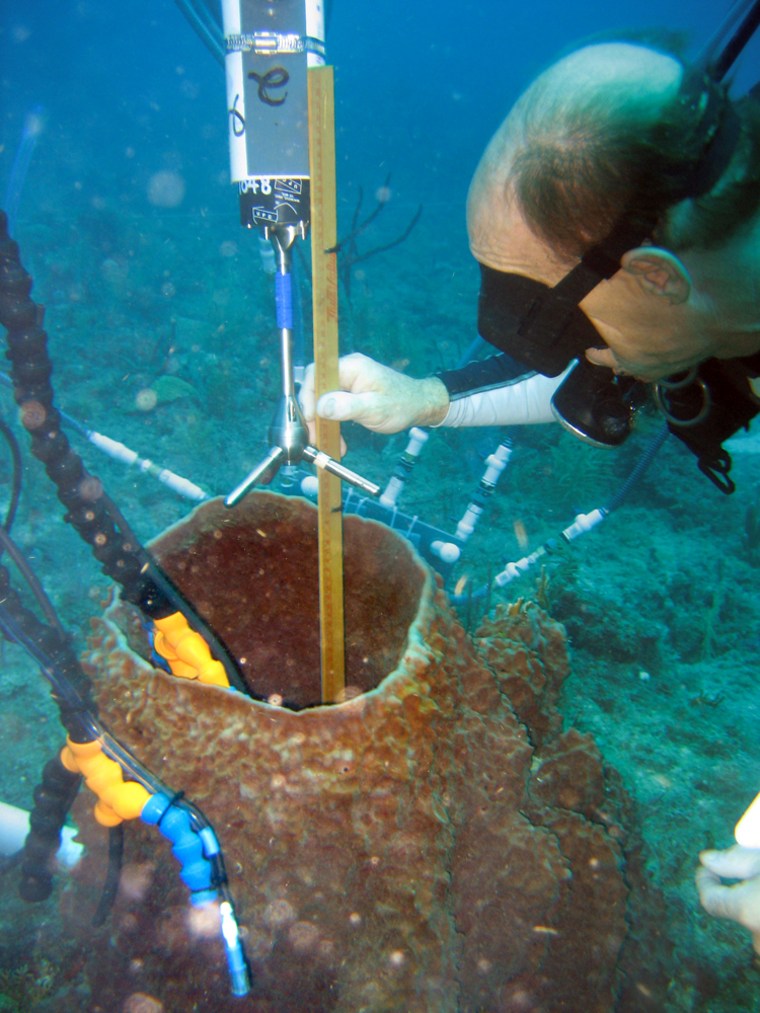

Researchers will study sponge biology and coral reefs — fertile marine habitats that are threatened around the world by disease, rising ocean temperatures and human factors such as pollution and overfishing.

Bus-sized habitat

Aquarius is a yellow, 43-foot-long (13-meter-long), 9-foot-diameter (2.75-meter-diameter) tube, roughly the size of a school bus. It lets researchers dive for nine hours a day and return to the habitat without standard scuba diving requirements of surfacing and decompressing.

This is the first time that live classes will be conducted from Aquarius Reef Base. A school in Florida and another in Michigan are getting direct interactive feeds, as are the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and UNC's Institute of Marine Science in Morehead City.

Other classes can follow the team online at Oceanslive.org, which has round-the-clock live video of the mission.

Using a system of cables that stretch out from Aquarius, divers will visit sites they have studied in the past to determine if any long-term change has taken place.

Studying more than coral

On most reefs around the world, the abundance of hard coral has declined, and the cover of soft algae has increased, said Steve Gittings, science coordinator with NOAA's National Marine Sanctuary Program. Algae is a natural part of the ocean ecosystem, but it can respond to human influences such as pollution to create large or unnatural concentrations that can displace corals.

Researchers also want to learn more about two other reef dwellers, sponges and soft corals, because it's not clear whether their abundance has significantly changed, Gittings said. Also of interest are the suspected causes of change in reef ecosystems, which may include a mass die-off of a long-spined sea urchin that ate algae, Gittings said.

"We're seeing dramatic changes literally on reefs around the world with regard to the relationship between all those different components that live on the bottom," Gittings said.

One of those components is sponges, which pump water through their bodies to filter food particles and produce dissolved nitrogen, a fertilizer.

The Aquarius team will investigate any links between changes of reef compositions and organic matter processed by sponges, seeking to discover whether sponges are fertilizing grasses that compete with corals, said researcher Chris Martens of UNC-Chapel Hill.

"Corals have gone through huge changes in terms of being totally dominant in oceans to being lesser," said Martens. "We're asking the question, 'Do sponges help or hurt in that process?'"

20-year-old underwater home

Aquarius, owned by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, operated by the University of North Carolina-Wilmington and used by the Navy and NASA, was built in 1986. It began operating in the U.S. Virgin Islands before being redeployed off Key Largo in 1993.

The facility has bunk beds and showers; a microwave, refrigerator and sink; and the computer and diving equipment needed to research reefs and collect, assemble and relay data.

"It's not claustrophobic, really," said Prager, the chief scientist.

Food, computers and other equipment are sent down using pots that can handle two and a half times normal atmospheric pressure below the ocean's surface.

After the expedition, the aquanauts must decompress for 17 hours or they will get the crippling "bends."

"We don't want to fizz," Martens said.

A surface buoy provides air, power and communications to Aquarius through hoses, cords and cables. On land, a crew monitors the living conditions in the facility.

The aquanauts eat microwaved or reconstituted meals. Food must be sent down via the special pots or it will not stand the pressure.

"A Pringles can can turn into a pretzel," Martens said.

Eating is one of the things about living underwater that takes some adjustment, Prager said.

"Things tend to taste very bland," she said. "There's a lot of hot sauces down there."