After suffering its share of dark days, NASA's Dawn mission finally had its “day in the sun” with Thursday morning’s launch toward our solar system's main asteroid belt.

The sun nearly set on Dawn a year and a half ago, when NASA canceled the mission over concerns about its ion engine. After a review of the planned improvements for the spacecraft, the space agency resurrected the project — but that wasn't the end of the mission's setbacks. Its originally scheduled June launch date was ruined by a processing accident involving its booster rocket.

That delay might have been a blessing in disguise, said Dawn mission designer Mark Rayman of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“A complex combination of myriad factors, including the positions of Earth in its orbit on candidate launch dates in 2007, of Mars in its orbit in the first few months of 2009, and of Vesta in its orbit late in 2011, makes the new launch more favorable for the mission,” he explained in a pre-launch newsletter. “Although still a challenge of astronomical proportion, this will make it slightly easier for Dawn to complete its assignment.”

Dawn is facing a “slightly easier” flight path than it would have in June, thanks to the enhanced reserves that the probe now has for emergencies, Rayman said. “This may be translated to slightly greater resilience in keeping its alien appointments, should it encounter difficulties on its voyage through the unforgiving and remote depths of space,” he wrote.

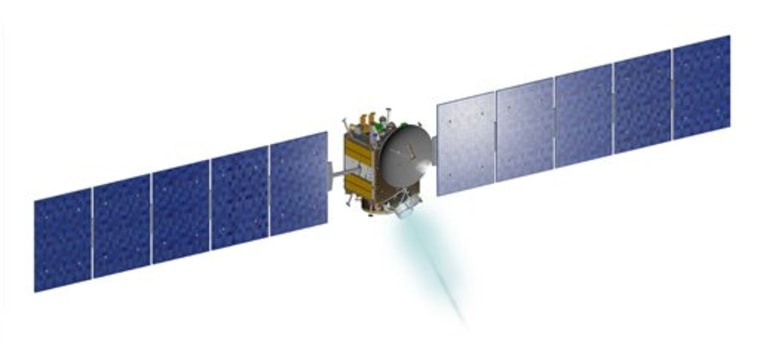

Space probes bound for the outer solar system have flown past a number of asteroids during previous missions, and two probes (NASA's NEAR Shoemaker and Japan's Hayabusa) have even orbited and landed on asteroids that pass through the inner solar system. But this is the first mission to investigate big asteroids in the so-called Main Belt between Mars and Jupiter. As it heads toward encounters with two “minor planets” (Vesta and Ceres), Dawn will be carrying some major hardware features that include the most powerful electrical system and propulsion system ever installed on an interplanetary spacecraft.

Small push adds up to big impulse

These two impressive features are related. The probe will use a xenon-fueled ion drive system first tested on the Deep Space 1 interplanetary mission a decade ago. It has three steerable ion engines that will have to operate for half of the 10-year mission. The system has enough propellant to change velocity by a total of 10 kilometers (6 miles) per second over the course of the mission. This "total impulse" is far higher than that of any previous interplanetary spacecraft, and bigger than the total impulse delivered by the Delta 2 launch vehicle that Dawn rode into space.

The impressive total impulse is balanced by its extremely small push on the spacecraft, a push sometimes poetically compared to “a butterfly’s burp.”

Dawn carries solar arrays that span 65 feet (20 meters) and generate 10 kilowatts at Earth’s distance from the sun — four times as powerful as the arrays on Deep Space 1. It also has a set of hydrazine-fueled attitude control thrusters for controlling the probe’s orientation, These jets can also be used to make quick course corrections if necessary.

Dawn’s ion-drive low-thrust trajectory will spiral out from the sun, make a gravitational-assist flyby of Mars in February 2009, and arrive at Vesta in October 2011 for a six-month visit. It will then head for Ceres, arriving in February 2015.

The ion engine is also used to spiral down into a 435-mile (700-kilometer) survey orbit of each target asteroid, all the while searching for navigation hazards such as small moons and dust. It will then lower its closest point to less than 50 miles (75 kilometers) for high-resolution imaging.

Probing solar system’s history

Dawn carries cameras as well as instruments to determine the composition of the surfaces of these asteroids. Earlier plans to carry a magnetometer and a laser altimeter had to be abandoned.

The data resulting from Dawn should provide fresh insights about the solar system’s origins and evolution. Vesta’s surface is believed to be the source of about 5 percent of meteorites that fall to Earth, probably blasted off the asteroid by a collision millions of years ago. It appears covered with basaltic lava flows which might be magnetized —a big surprise for such a small body that shouldn’t have ever melted. It also seems to have a massive south pole crater basin.

Ceres shows evidence of a primitive surface and thin atmosphere, with seasonal frost deposits. The surface rock and dust possibly cover a thick layer of water ice. And under certain conditions of pressure and temperature deep below the surface, portions of that ice may actually have melted, creating a potential location for biochemical processes. Like the under-ice water oceans of Io, Ganymede and other moons, such bodies of liquid water are potential sites for living organisms — although Dawn is not instrumented to detect them.

So all in all, even though it is a mission to the minor planets, there’s nothing “minor” about this spacecraft, or about the expected science discoveries on its targets, these remnants of the raw material from the birth of the solar system.

James Oberg, space analyst for NBC News, spent 22 years at the Johnson Space Center as a Mission Control operator and an orbital designer.