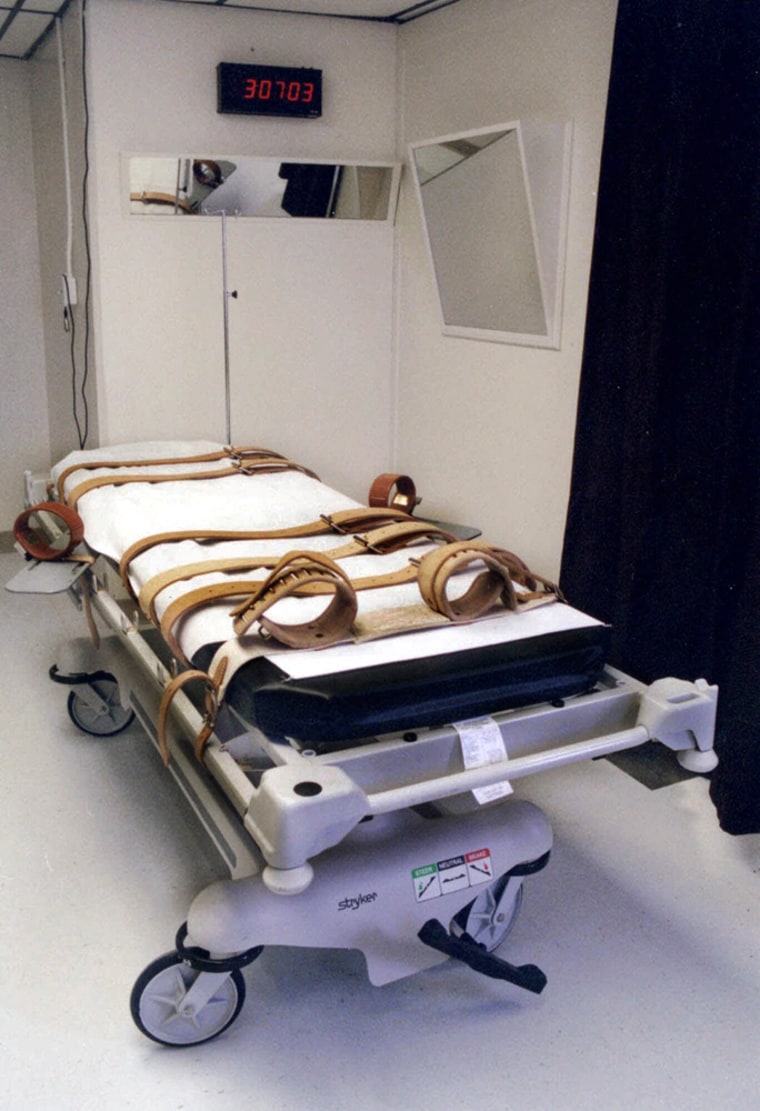

Lethal injection was supposed to be the humane, enlightened way to execute inmates and avoid the pain and the gruesome spectacle of firing squads, the electric chair and the noose.

But now it, too, is under legal attack as cruel and unusual, with the U.S. Supreme Court agreeing this week to hear arguments that lethal injection can cause excruciating pain.

Some supporters of the procedure say the notion that inmates suffer is unproven. And they argue that there is nothing wrong with lethal injection itself; instead, they say, the problem is inadequately trained executioners.

In fact, the man who developed the procedure 30 years ago said it is similar to the simple injections given every day in hospitals.

“What causes it to go wrong is that the protocols aren’t carried out properly,” said Dr. A. Jay Chapman, former Oklahoma medical examiner.

If an execution is about as simple as an ordinary injection, what, then, can go wrong?

Deadly chemical cocktail

In the three-drug process used by most of the 38 states that practice lethal injection, sodium pentothal is given first as an anesthetic and is supposed to leave the inmate unconscious and unable to feel pain. It is followed by pancuronium bromide, which paralyzes the inmate’s muscles, and then potassium chloride, which stops the heart.

Foes of capital punishment argue that if the inmate is not properly anesthetized, he could suffer extreme pain without being able to cry out.

That could happen in a number of ways: The executioner could inaccurately calculate the dosage needed for an inmate of a given body weight. Or the executioner could fail to administer the full amount, mix the drug improperly, or wait too long between giving the anesthesia and the lethal substance.

In Missouri, a doctor who participated in dozens of executions was quoted recently as saying he was dyslexic and occasionally altered the amounts of anesthetic given.

A botched execution in Florida last year illustrated another way a lethal injection could go awry: Angel Nieves Diaz needed a rare second dose of chemicals — and the execution took a half-hour, twice as long as normal — after the needles were mistakenly pushed clear through his veins and into the flesh of his arm. That left chemical burns in his arm that opponents say probably caused him extreme pain.

During the process, Diaz appeared to grimace. But he did not specifically say he was suffering. And a state panel was unable to determine if Diaz had been properly sedated or if he felt pain.

There is no direct proof that inmates have suffered while undergoing lethal injection. After all, they don’t live to tell about the experience.

Study: Anesthetic can wear off before death

But opponents of lethal injection often cite a 2005 study in the British medical journal The Lancet indicating that the anesthetic can wear off before an inmate dies. The study involved 49 U.S. executions. In 21 of the deaths, the study found, inmates were probably conscious when they received the final drug that stops the heart.

Chapman said that he has not seen definitive proof inmates suffer, and that, in any case, the pain would be small.

“Who’s to say exactly how much pain that an individual — of varying, different persuasions — can experience with the injection of potassium chloride? But I don’t think that in any sense of the word it can be described as excruciating,” he said.

One major issue is how to measure the inmate’s level of consciousness after the anesthetic is given.

State measures brain activity

Execution opponents say they believe North Carolina is the only state using a device common in operating rooms to measure brain activity. The state Corrections Department anesthetizes the inmates and waits for their brain activity to dip to a level indicating they are sedated before pushing in the lethal drug.

“It’s worked well for us as a tool” in the two executions in which it has been used, department spokesman Keith Acree said of the bispectral index monitor.

Fordham Law School professor Deborah Denno said the problems she sees with executions cannot be easily fixed with technology.

“You need to get better people, get better drugs and have more scrutiny of the process,” said Denno, who frequently testifies about capital punishment.

AMA bars doctors from participating

Similarly, Richard Dieter, executive director of the Washington-based Death Penalty Information Center, which opposes executions, said that lethal injection is essentially “a medical procedure being performed by non-medical persons. These are drugs and procedures borrowed from operating rooms.”

But many states find it hard to get doctors to take part because the American Medical Association’s code of ethics bars members from participating in executions.

Chapman scoffed at the idea that executioners need to go to medical school to do the job right, saying people could easily be trained. And he suggested that switching to other drugs would not make any difference.

“The new drugs are simply just replays of the old ones,” he said.

Denno said states have been hesitant to look at alternative chemicals, because they like to be able to argue that all the other states are using the same mixtures. “There is safety in numbers,” she said.

At least a dozen states that use lethal injection have executions on hold because of legal challenges to the procedure. The Supreme Court stepped into the debate this week when it agreed to hear a case from Kentucky.

Denno said she hopes the high court will provide direction to states on what changes are needed to ensure the process is constitutional.

“The best that could happen is that they come up with a standard and have states follow that,” she said.