The Space Age began 50 years ago this week with the launch of Sputnik 1, a small metallic ball carrying only a couple of simple radio transmitters. Since then, spaceflight technologies have grown up. High-performance rocket fuels, miniaturized guidance electronics and ultra-light spacecraft materials, to name a few, make frequent and complex trips to space possible.

During the next half century, however, leaders in spaceflight planning think cost-cutting technological innovations will carry the torch to the moon, Mars and beyond.

"Getting into space is very expensive. If there's a way to really reduce the cost of getting into Earth orbit by a factor of 10, that would be something," said Chris Moore, NASA's program executive for exploration technology at the agency's headquarters in Washington, D.C. "There's a whole bunch of innovative ideas ranging from scramjet propulsion to space elevators, but some of those ... are very far in the future."

Brett Alexander, executive director for space prizes at the X Prize Foundation in Santa Monica, Calif., said new propulsion systems should help pave the way for more technologies.

"The biggest challenge is to make a simpler and safer propulsion system that can be mass-produced," Alexander told SPACE.com. "It's a tipping point not only for spaceflight itself, but also for the technologies that would follow."

While scientists across the globe plug away at the problem of developing discount propulsion systems, Moore explained that NASA is advertising its "wish list" as the Centennial Challenges.

"We offer cash prizes to industry or universities to do low-cost, highly innovative missions and technology demonstrations," Moore said of the program. The proof-of-concept tasks include developing more dexterous and durable astronaut gloves, extracting breathable oxygen from moon dust and creating incredibly strong yet lightweight "tethers" that a space elevator might use to hoist itself into space.

Although challenge winners through 2005 have been scarce, Moore is confident upcoming events, such as Google and the X Prize Foundation's "Moon 2.0" lunar lander challenge, will generate success.

"These types of competitions have been successful in the past," Moore said, citing Burt Rutan's suborbital flight of a privately funded spacecraft in 2004, which snatched up $10 million in prize money.

Regolith-ready technology

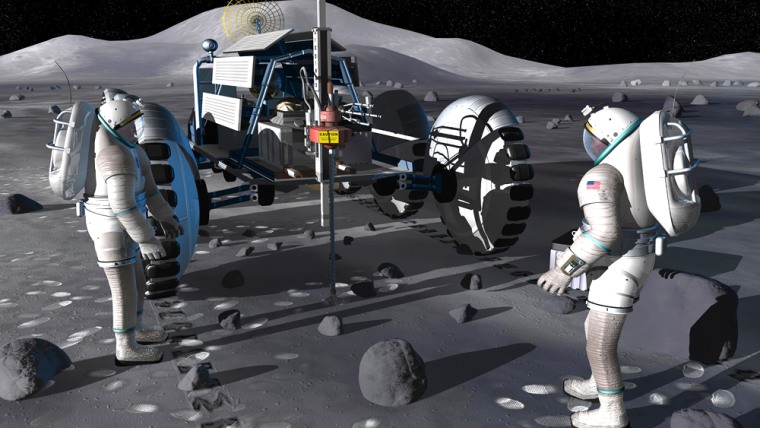

As privately funded teams try getting their cost-effective landers on the moon, NASA is gearing up for humanity's extended stay there around 2020—but getting there will only be half the battle, Moore said.

The lunar surface is powdered with microscopic shards of glassy dust, known as regolith, which threatens both man and machine. Moore said creating a functional base on the lunar surface requires developing "regolith-ready" technology.

"Regolith can degrade spacesuits and pressure seals and other equipment," Moore said. The health danger during long stays is also an issue, he said, mentioning that astronauts returning from the moon complained about breathing problems from dust that was tracked into their tight living space.

Dust-combating technologies could be as complex as special dust-removing chambers or as simple as spacesuit coveralls, Moore said. He noted that lunar habitats able to recycle air, water and human waste far more efficiently than the International Space Station's systems will also be key.

"Once we're there, we need advanced robotics to deploy the habitat modules and connect them together to form a lunar outpost," he said. "What we'd like to do is take the lunar regolith and extract oxygen from minerals in the soil, so we can use it to breathe or make oxidizer for rocket fuel."

Mars and beyond

The technologies developed for long-term moon missions will serve as templates for Mars expeditions some time after 2030, but Moore said further innovative advances will be necessary to get astronauts there — and back — in one piece.

"The faster we can get there the better," Moore told SPACE.com. He thinks that yet-to-be-developed nuclear propulsion systems may prove to be the fastest form of spaceflight in the future, as well as sending a mission in two trips: A heavier supply-loaded spacecraft ahead of time, followed by a speedy lightweight manned spacecraft.

Moore said that faster speeds will cut exposure time to the health threats to crewmembers during their journey, such as radiation, bone wasting and immune deficiencies, but advanced medical technologies will also be crucial to success.

"When we go to Mars it's going to be a very long trip," he said. "We need to make sure the crew is healthy and can perform their job when they get there."

A private matter?

Building a strong, privately involved space economy will be essential to successfully develop technologies able to send representatives of the human race to Mars, Alexander said.

"We can't sustain programs like Apollo in the future, just like we couldn't 40 years ago," Alexander said. "My dream is to have sustainable and accessible access to space, and I firmly believe that you have to get the private sector involved to achieve that."

Moore agreed, noting that NASA intends to use their lunar outposts to provide infrastructure for private industry. Yet the prowess of a single country's space-based industries may not be enough.

In addition to private involvement, Moore explained that ever-better international collaboration will be essential for putting new technologies to use in the next era of spaceflight.

"The first few years of the Space Age were characterized by a lot of international competition, but we're in a much more collaborative environment now," Moore said. "(Spaceflight) is a very expensive and challenging endeavor, and we'll have to depend on other nations ... in the next 50 years."