The White House is pushing the Senate to ratify a long-spurned high seas treaty that has gained new relevance with the melting of the polar ice cap and anticipated competition for the oil that lies below.

President Bush says U.S. approval of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, concluded in 1982 and in force since 1994, would give the United States "a seat at the table" when rights over natural resources are debated and interpreted.

"The United States needs to join the Law of the Sea Convention, and join it now," Deputy Defense Secretary Gordon England told senators recently. He stressed that it would give legal clarity to U.S. naval operations.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which held a second round of hearings on the treaty Thursday, appears ready to vote on it. That would set up a full Senate vote on ratification by year's end. A small group of senators has blocked action on the treaty for years.

"Far from threatening our sovereignty, the convention allows us to secure and extend our sovereign rights," said the committee chairman, Sen. Joseph Biden, D-Del.

Currently 155 nations, including all major allies of the U.S. and maritime powers such as Russia and China, are party to the convention. The treaty defines rights on uses of the sea, sets rules for navigation, fishing and economic development and establishes environmental standards.

In limbo since 1994

While the U.S. adheres to most provisions, President Reagan opposed the treaty because of a section dealing with deep seabed mining. Even after that section was overhauled in 1994 to satisfy U.S. concerns and President Clinton signed it, Congress has showed little interest in ratification.

Three years ago, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee endorsed it unanimously, but the full Senate never took it up.

Opponents say it would impinge on U.S. military and economic sovereignty.

"It's one more erosion of our sovereignty," said Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-Okla., long an outspoken opponent of the treaty. He contended that none of the issues raised by Reagan, including the ceding of economic and security authority to international bureaucrats, has changed.

If Democrats do not allow hearings on the treaty, Inhofe said, "I'll exercise everything I personally can" in the Senate to oppose it.

The Coalition to Preserve American Sovereignty, a group opposed to the treaty, warned in letters to the Senate that it would force the U.S. to abide by mandatory dispute resolution, restrict Navy and Coast Guard activities and subject Americans to environmental standards dictated by the Kyoto Protocol.

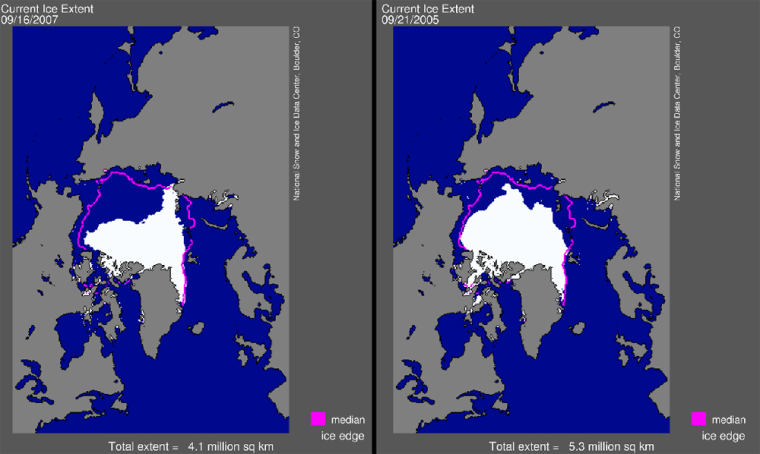

But Congress and the White House have come around on the issue as global warming opens up the possibilities of exploiting resources frozen under polar ice.

Other nations reacting

In August, Russia sent two small submarines to plant a tiny national flag under the North Pole. Denmark has sent scientists to gather evidence that the mountain ridge under the Arctic Ocean is attached to its territory of Greenland. Canada is talking about increasing its icebreaker fleet and setting up military facilities along what could be the long-sought-after Northwest Passage between Europe and Asia.

"Recent Russian expeditions to the Arctic have focused attention on the resource-related benefits of being a party to the Convention," Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte said in Senate hearings last month.

"Currently, as a nonparty, the United States is not in a position to maximize its sovereign rights in the Arctic or elsewhere," Negroponte said.

The treaty recognizes sovereign rights over a country's continental shelf out to 200 nautical miles and beyond if the country can provide evidence to substantiate its claims.

It gives Arctic countries 10 years after they ratify the treaty to prove their claims under the largely uncharted polar ice cap. The United States, with its Alaskan coast, is the only Arctic nation that is not party of the treaty.

Negroponte, who has also held the positions of U.N. ambassador and director of national intelligence, said the treaty in no way would impede the Navy's navigational freedom, interfere with the interception of suspicious vessels or impair U.S. intelligence and submarine activities.

"We have more to gain from legal certainty and public order in the world's oceans than any other country," he said.