Space exploration has been populating the solar system with manmade hardware for half a century, and last month marked the 50th anniversary of Sputnik, the planet’s first artificial satellite. But an even more significant breakthrough occurred less than a month later, on Nov. 3, 1957, when space hardware began carrying life forms into long-duration orbits.

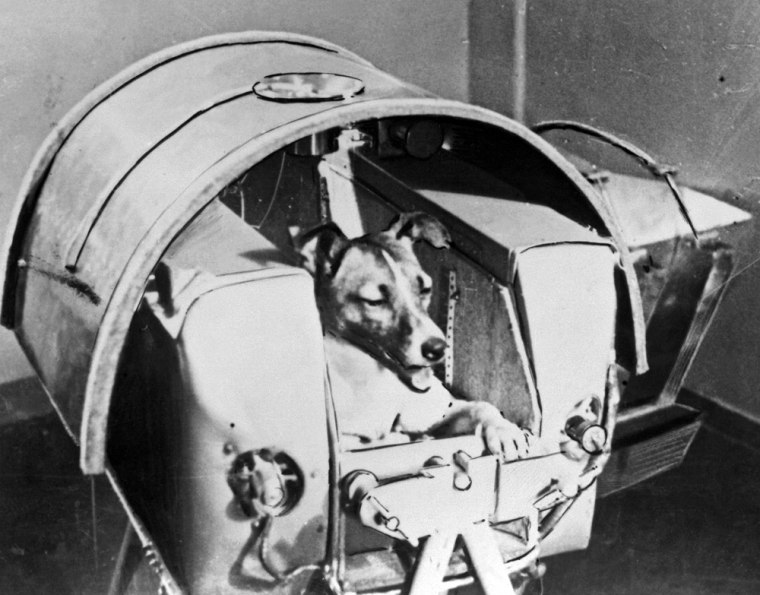

This Saturday marks the 50th anniversary of that milestone mission — the Russian Sputnik 2 launch that put a dog named Laika into orbit. Most of the remembrances of "Muttnik" may focuse solely on the first dog in space and her sad fate. But in the annals of the expansion of earthly life to the universe beyond, the full story is much more profound.

Laika's flight marked the beginning of a pilgrimage that has brought terrestrial life forms to the moon and very likely far beyond. That pilgrimage will only expand in the coming decades, and will surely have far wider significance than it has to date.

Even during that first flight, Laika did not ride alone. Like all advanced organisms on Earth, the dog carried an array of microorganisms in every nook and cranny of her body. Laika herself died of overheating just a few hours after launch, due to a thermal control system failure — a fact concealed by the Russians for decades. But that was hardly the end of the voyage.

The other living organisms in Sputnik 2 would have continued to thrive for the nearly six months the satellite remained in orbit, living off the biological materials and water provided by Laika’s body. Temperatures inside the inert vehicle were well within the range in which Earth life can function, and the pressurized cabin would have remained intact.

Everything was destroyed — and likely sterilized — when the satellite slipped into the upper atmosphere on April 14, 1958. The forms that the "Laika biosphere" took can only be speculated about. But some microbes almost certainly survived until the very end.

A decade later, an even bolder small step for earth germs may have occurred when a worker at a spacecraft workshop in California sneezed on a television camera he was assembling. Installed in the Surveyor 3 robot moon lander, the device landed on the moon in April 1967. Apollo 12 astronauts retrieved samples of the lander in November 1969, and when several spots inside the camera were tested in a laboratory for microorganisms, one sample turned out to provide viable human-borne germs.

The interpretation of this test remains dubious, since it turned out the tester was so skeptical of positive results he was careless with quarantine protocols and had laid the sampling swabs on a surface outside of the controlled area. So the germs could have been his own. Still, the coincidence that the one success was with the swab from the most interior section of the camera remains suggestive.

The idea that microorganisms could have survived a trip out to the moon and then two and half years of lunar surface temperature and radiation conditions remains plausible, since conditions in the camera housing were calculated to lie within known survival ranges for Earth life. That idea has a broader but still widely unrecognized implication: Such conditions — exposure to terrestrial contamination during manufacture, followed by protection in a survivable environment after launch — also could apply to dozens of other space vehicles that have been launched to the moon, Mars and Venus. This is particularly true for Russian space probes, where deliberately pressurized canisters hold the electronics.

It’s impossible to know how long microbes or spores could survive in dormant state. Certainly, barring an accidental splash or two of borscht, they would have had no nourishment for growth. Maybe someday it will be possible to retrieve one of those early interplanetary probes and take a look — if the descendants of its original inhabitants permit it!

Closer to Earth but still in space, the lustiness of microbial growth is strikingly illustrated by experience on long-term space stations, such as Skylab (where bacteria probably thrived for years on garbage and human waste in the craft's trash module) and on the Russian Mir station, where fungi colonies actually grew on portholes (feeding on human skin peelings) and were so thick they obscured the view.

The fungi on Mir also excreted highly corrosive waste products that actually etched into the porthole glass and its titanium frame. Russian scientists found that the fungi and other microorganisms mutated wildly in the higher radiation levels of space.

Those "space colonies" ended in extinction when Skylab burned up in 1979 and Mir in 2001, but the international space station is the latest host for Earth life. Humans, and small numbers of their experimental animals, are minority colonists there. The vast majority of earth creatures now living off the planet are almost too small to be noticed, but their future impact may be far larger than our own.

Researchers already have found that when salmonella bacteria were carried into orbit, they morphed into a new strain that was even deadlier when it was brought back to Earth. In the far future, the most dangerous space aliens might turn out not to be aliens at all — but rather the creatures we've been bringing with us to the final frontier, starting 50 years ago with one dog and several million microbial hitchhikers.

James Oberg, space analyst for NBC News, spent 22 years at the Johnson Space Center as a Mission Control operator and an orbital designer. He is the author of several books about the U.S. and Soviet space programs, including "Red Star in Orbit" and "Star-Crossed Orbits."