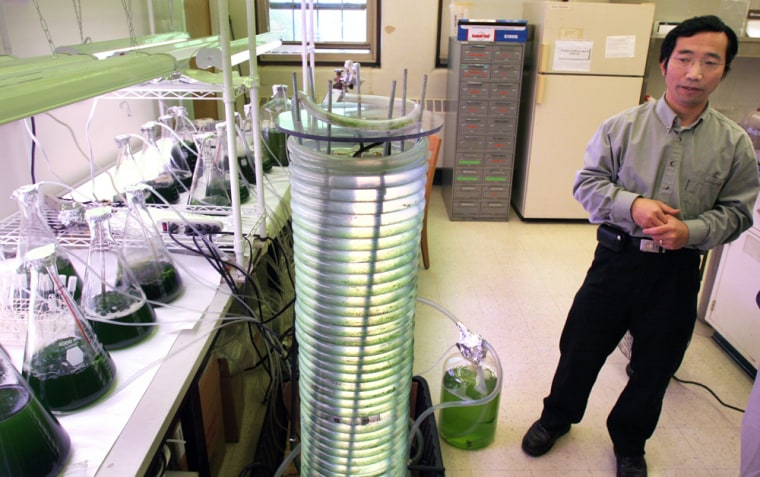

The 16 big flasks of bubbling bright green liquids in Roger Ruan's lab at the University of Minnesota are part of a new boom in renewable energy research.

Driven by renewed investment as oil prices push $100 a barrel, Ruan and scores of scientists around the world are racing to turn algae into a commercially viable energy source.

Some varieties of algae are as much as 50 percent oil, and that oil can be converted into biodiesel or jet fuel. The biggest challenge is slashing the cost of production, which by one Defense Department estimate is running more than $20 a gallon.

"If you can get algae oils down below $2 a gallon, then you'll be where you need to be. And there's a lot of people who think you can," said Jennifer Holmgren, director of the renewable fuels unit of UOP LLC, an energy subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc.

Researchers are trying to figure out how to grow enough of the right strains of algae and how to extract the oil most efficiently. Over the past two years they've enjoyed an upsurge in funding from governments, the Pentagon, big oil companies, utilities and venture capital firms.

The federal government halted its main algae research program nearly a decade ago, but technology has advanced and oil prices have climbed since then, and an Energy Department lab announced in late October that it was partnering with Chevron Corp., the second-largest U.S. oil company, in the hunt for better strains of algae.

"It's not backyard inventors at this point at all," said George Douglas, a spokesman for the Energy Department's National Renewable Energy Laboratory. "It's folks with experience to move it forward."

A New Zealand company demonstrated a Range Rover powered by an algae biodiesel blend last year, but experts say it will be many years before algae is commercially viable. Ruan expects some demonstration plants to be built within a few years.

Converting algae oil into biodiesel uses the same process that turns vegetable oils into biodiesel. But the cost of producing algae oil is hard to pin down because nobody's running the process start to finish other than in a laboratory, Douglas said. One Pentagon estimate puts it at more than $20 per gallon, but other experts say it's not clear cut.

If it can be brought down, algae's advantages include growing much faster and in less space than conventional energy crops. An acre of corn can produce about 20 gallons of oil per year, Ruan said, compared with a possible 15,000 gallons of oil per acre of algae.

An algae farm could be located almost anywhere. It wouldn't require converting cropland from food production to energy production. It could use sea water. And algae can gobble up pollutants from sewage and power plants.

The Pentagon's research arm, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, is funding research into producing jet fuel from plants, including algae. DARPA is already working with Honeywell's UOP, General Electric Inc. and the University of North Dakota. In November, it requested additional research proposals.

As the single largest energy consumer in the world, the Defense Department needs new, affordable sources of jet fuel, said Douglas Kirkpatrick, DARPA's biofuels program manager.

"Our definition of affordable is less than $5 per gallon, and what we're really looking for is less than $3 per gallon, and we believe that can be done," he said.

Des Plaines, Ill.-based UOP — which has developed a "green diesel" process that converts vegetable oils into fuels that are more like conventional petroleum products than standard biodiesel — already has successfully converted soybean oil into jet fuel, Holmgren said. And the company has partnered with Arizona State University to obtain algae oil to test for the DARPA project, she said.

At the University of Minnesota, Ruan and his colleagues are developing ways to grow mass quantities of algae, identifying promising strains and figuring out what they can make from the residue that remains after the oil is removed.

Because sunlight doesn't penetrate more than a few inches into water that's thick with algae, it doesn't grow well in deep tanks or open ponds. So researchers are designing systems called "photobioreactors" to provide the right mix of light and nutrients while keeping out wild algae strains.

Ruan's researchers grow their algae in sewage plant discharge because it contains phosphates and nitrates — chemicals that pollute rivers but can be fertilizer for algae farms. So Ruan envisions building algae farms next to treatment plants, where they could consume yet another pollutant, the carbon dioxide produced when sewage sludge is burned.

Jim Sears of A2BE Carbon Capture LLC, of Boulder, Colo., a startup company that's developing fuel-from-algae technologies that tap carbon dioxide from coal-fired power plants, compared the challenges to achieving space flight.

"It's complex, it's difficult and it's going to take a lot of players," Sears said.