John Bruno didn't attend the U.N. climate talks at Bali, Indonesia, in December 2007, but he did have advice for delegates looking to take in the resort's reefs: enjoy it now, because if sea temperatures continue to rise, expect to see more — and more severe — disease outbreaks that wipe out corals.

Bruno has the credentials to back up his advice. A marine biologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, he co-authored two 2007 studies on rapid coral decline and on a link between coral disease and global warming.

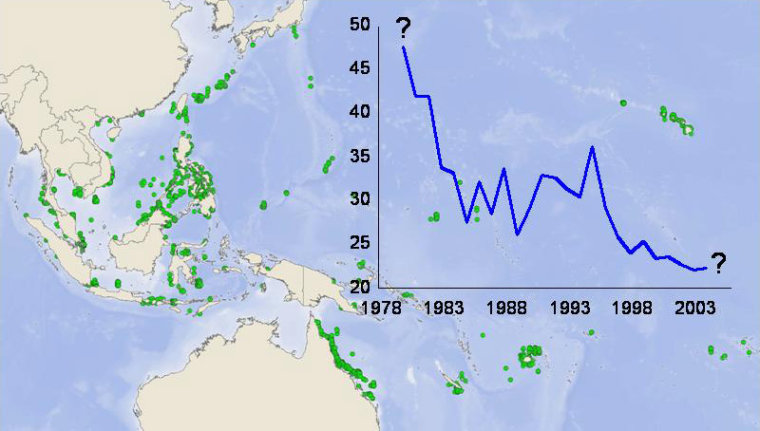

One study found that coral coverage in the Indo-Pacific — an area stretching from Indonesia’s Sumatra island to French Polynesia — dropped 20 percent in the past two decades. That rate is much higher than Bruno's team had expected.

Moreover, 600 square miles of reefs disappeared since the 1960s, the study found, and the losses were just as bad in Australia’s well-protected Great Barrier Reef as they were in marine reserves in the Philippines, where funding protection is problematic.

Bruno suspected warming ocean temperatures were playing a big role and the second study — which focused on the Great Barrier Reef — provided a strong connection.

That study compared new sea temperature data to six years of reef health surveys. The team found a strong correlation between white syndrome, a potentially fatal disease, and warmer waters.

"Our results suggest that climate change could be increasing the severity of disease in the ocean, leading to a decline in the health of marine ecosystems and the loss of the resources and services humans derive from them," the team concluded.

Unusually warm waters can also cause coral "bleaching," where microscopic algae that live within the corals' tissue and provide it with most of its nutrition are literally expelled. In the most severe cases, that literally kills entire coral colonies.

Reefs as forests

Even before any warming impact, reefs have long been stressed by runoff from farms, human sewage and fishing practices — including the use of dynamite to stun and then capture reef fish for the aquarium trade.

"At least half of the world’s living reefs were lost during the latter half of the 20th century," Bruno notes.

He and other experts fear that another third could be gone in 30 years.

For Bruno, coral reefs don't get the credit they deserve. He compares them to forests in that both create a complex ecosystem that is home to thousands of associated plants and animals.

Covering just one percent of the ocean floor, reefs are far less common than rainforests, he notes, and yet "we are losing reef-building corals globally at a rate of about one percent a year, which is about twice the rate of tropical rainforest loss."

Three quarters of all reefs are in the vulnerable Indo-Pacific, where they provide shelter for island communities and are a key source of income, mostly from the benefits of fishing and tourism.

Hope for some species

Besides any help that governments might provide, Mother Nature herself appears to have some tools to protect at least some coral species.

A December 2007 study by the Wildlife Conservation Society found that corals in "tough love" seas with wide-ranging temperatures are more likely to survive warming waters than corals in what had been stable environments.

"This finding is a ray of hope in a growing sea of coral bleaching events and threatened marine wildlife," lead author Tim McClanahan said in a statement. "With rising surface temperatures threatening reef systems globally, these sites serve as high diversity refuges for corals trying to survive."

The study examined temperature variations and coral bleaching events off East Africa from 1998 to 2005.

"The findings are encouraging in the fact that at least some corals and reef locations will survive the warmer surface temperatures to come," added McClanahan. "They also show us where we should direct our conservation efforts the most by giving these areas our highest priority for conservation."

For Bruno, the study reflects "nifty mechanisms of adaptation" by some coral species.

But, he adds, "The key question is, 'Will the frequency and magnitude of stressors (e.g., of summertime warming events) increase so much or so rapidly that coral populations cannot keep pace?' This is a long-standing question in conservation biology."