Soup and pizza couldn’t explain the origins of life, so a researcher built a sandwich of an idea instead.

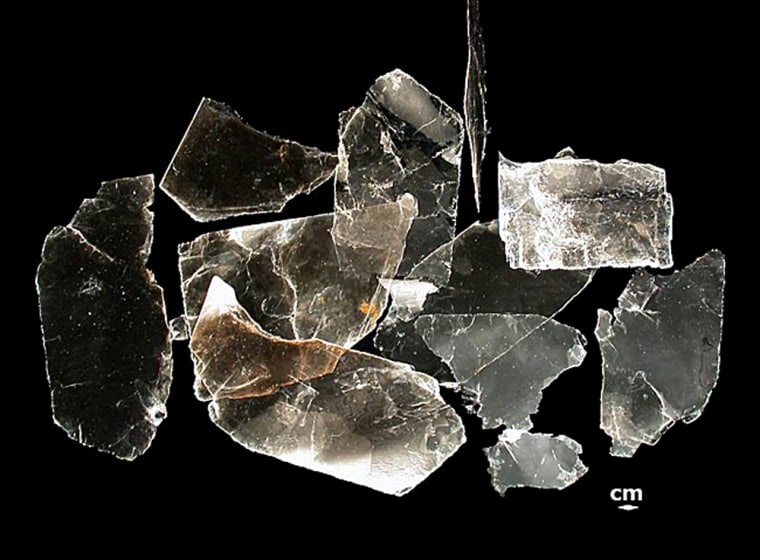

The new hypothesis describes how flaky layers of the mineral mica could have created the perfect conditions to jump-start the formation of molecules necessary for life.

Helen Hansma, a biochemist at the University of California at Santa Barbara, presented her idea for the first time Tuesday at the American Society for Cell Biology’s 47th annual meeting in Washington.

"Mica is like a massive sandwich with millions of layers of mineral sheets, which would be the bread," Hansma said. "The nooks and crannies between the bread may have jump-started the formation of life's chemicals and protected them. It's like a giant potluck of chemistry."

The competing chemical soup model deems that life formed in a sea of chemicals, but Hansma said it does not outline a good place for molecules to react with one another. Although the "pizza" postulates does, stating that molecular toppings formed on the surface of crusty minerals, Hansma said it falls short of linking basic biological chemicals together to form ribonucleic acid (RNA) and other crucial components.

To address these shortcomings, Hansma merged the soup and pizza ideas to create her sandwich hypothesis.

"The mineral surfaces between mica layers create reaction surfaces, the pre-biotic soup gives you the reactants and the tiny spaces shelter the whole process," she said. "Energy to power [the chemical reactions] would have come from shifting layers of mica, perhaps from something like ocean currents or sunlight."

She said mica — which is rich in potassium — might also explain to why our bodies rely so heavily on potassium instead of other element.

"Having potassium in the picture excites me a lot," Hansma said. "Few in the life origins field have really given thought to wondering why we have so much of it in our cells."

Hansma said early experiments her team has performed back up the sandwich idea, but cautioned that significant work lies ahead before she can make the hypothesis appetizing to other scientists.

"This idea is really new, but I've gotten a lot of positive feedback so far," Hansma told LiveScience a few days before her talk. "I'm really anxious to see how it fares in front of leaders in the life origins field."