Way back in the day when students still got suspended for coming to school with purple hair and black fingernails, I was this weird esoteric kid into the Who, David Bowie, Nina Hagen and Alice Cooper. I didn't have many friends.

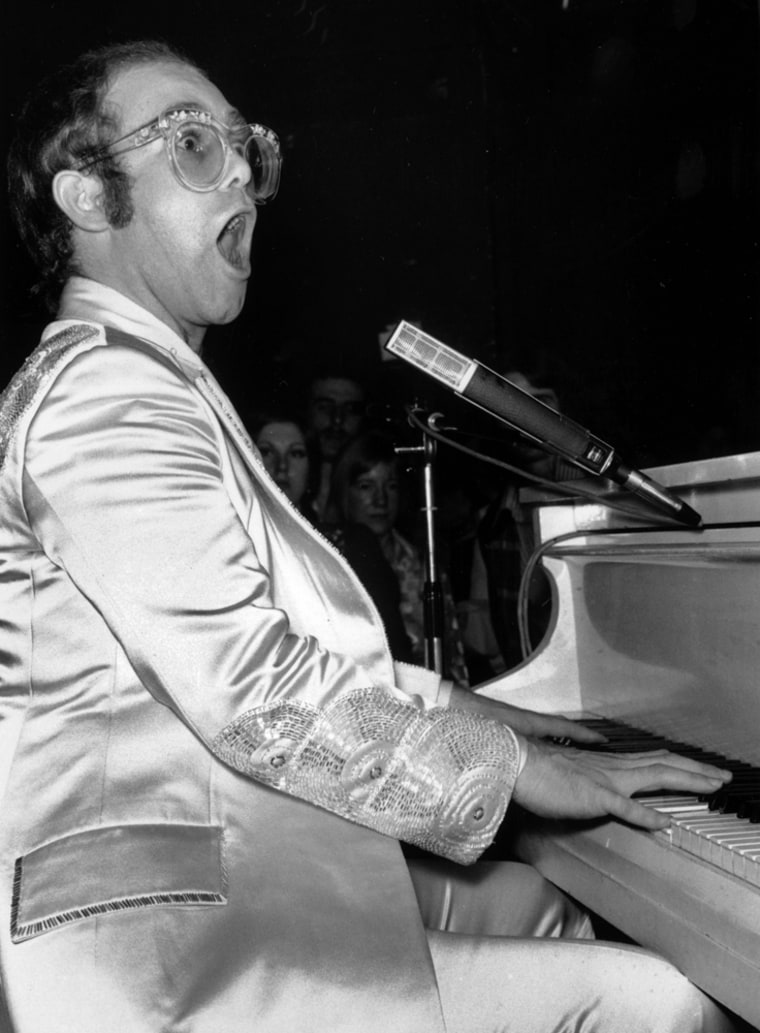

Then I met this other weird esoteric kid really into Elton John — an artist that I didn't know much about. So in the spirit of new friendship, my fellow outcast, "Bennie," brought in every single one of her Elton John records to school — on vinyl, as was the style of the day — for me to borrow.

This unrequested, but nevertheless generous and trusting gesture, necessitated that I carry her hefty stack of LPs on the bus and then 12 1/2 blocks home from the bus stop in the 3 p.m. Florida sun. A hardship, but worth it. Whether or not you appreciate the pop genius of "Captain Fantastic & the Brown Dirt Cowboy," everyone without amnesia knows such youthful exchanges are life-changing.

Here in the new millennium, a more convenient exchange commiserate with today's technology (via MP3s) would make Bennie a criminal. A pirate, if you want to be colorful. You know, like Johnny Depp.

Last week, Congress introduced the Prioritizing Resources and Organization for Intellectual Property Act (PRO IP Act), a bipartisan bill aimed at increasing civil penalties and criminal enforcement for copyright infringement, i.e., sharing MP3s.

This Draconian bit of legislation also proposed a new federal agency tasked with the management and enforcement, titled appropriately, WHIPER (White House Intellectual Property Enforcement Representative).

Meanwhile, across the blogosphere, outraged audiophiles argue the interpretation of this vague 69-page bill written in dense legalese. Does it mean you can't make an MP3 of music you've already purchased? Does it mean you can't make a mix CD and give it to your crush? Are you allowed to make an MP3 of music you've purchased as long as you don't place it in a file which others can access?

More cynically, maybe those in power will interpret the PRO IP Act on a case by case basis, in a way that suits best. Take, for example, this statement from Judiciary Committee Chairman John Conyers (D-Mich.): "By providing additional resources for enforcement of intellectual property, we ensure that innovation and creativity will continue to prosper in our society."

Um, what? How exactly does innovation and creativity prosper when ultimate utilization of new technology that allows others to share and access creativity at a rate never known before in civilization is crushed by legislation?

Note: This bill's introduction followed the $222,000 verdict in favor of the Recording Industry Association of America over a Minnesota mom who shared 24 songs on Kazaa. Much of the RIAA's ire and action, however, is aimed at college students — those historically noted for spreading innovation, creativity and ideas and at an exponential rate.

Currently, those kids caught sharing music via their college's IP are served $3,000 to $5,000 fines with the threat of a lawsuit if they don't pay up, not to mention academic penalties from some participating universities whether they pay the fine or not.

On the surface, it seems almost idiotic that so much time and money is lobbed against accidental pirates sharing music without malicious intent — especially when there's serious off-shore piracy raking in actual money from doing the same with videos.

The intent here is to teach its largest group of "end users" not to touch the stove. The RIAA is attempting to turn back the tide of so-called bad behavior record companies erroneously believe is ruining their industry. (That's right kids, Britney Spears, et al., ain't got nothin' to do with it!)

Here's why it won't work. Copyright law is antiquated. It wasn't ready for digital technology, and by the time concerned enterprises acknowledged the change afoot, the toothpaste was out of the tube. You can't beat it back with the blunt instrument of law.

You can't alienate your customer and expect him or her to remain loyal. What's more, it's the job of business to meet the needs of its customers, even if that means the business must change. That's capitalism.

Some people had a good guffaw over what they saw as the failure for Radiohead's recent "pay what you want" release on account of it didn't make the band ka-jillionaires. But it remains, as it began, a continuing experiment towards the interests of artst, business and "end user" on how this commerce must change. Hats off to Radiohead for thowing it out there.

Back in the day, my friend's Elton John collection encouraged me to buy my own. If she'd made me identical MP3s, I would've spent the money. However, I'd still shell out for Elton John concerts. Advertisements featuring Elton John songs catch my attention. I'll probably never see his Red Piano show in Vegas. And while I'm not much interested in any of his Disney soundtracks, I attended Elton John's charity garage sale.

Five years from now, we will see a new system of commerce take form. Record companies, TV stations and movie studios are not going to disappear. Artists, actors and musicians aren't going to perish for lack of monetary support.

How these relationships develop between agents, artists and "end users" will change. Not because of government oversight, but because habits will change and new markets will be built. Like all revolutions, it'll be a bloody one or a gradual change. Right now, the smart money's on bloody.