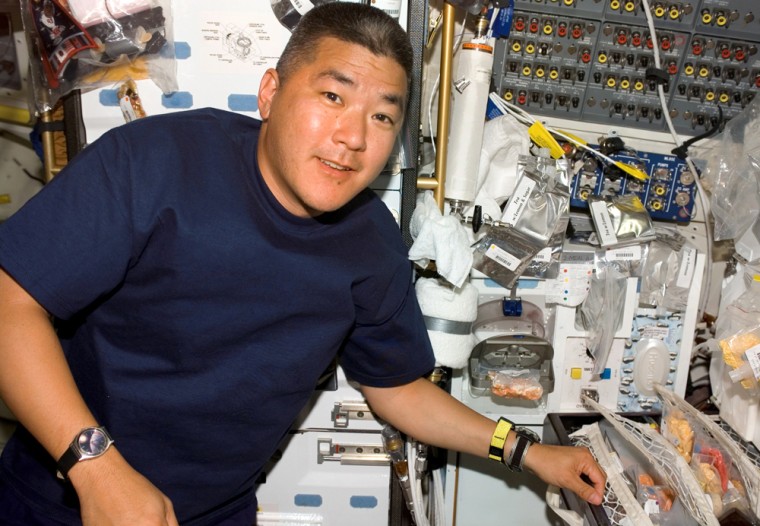

Daniel Tani's 90-year-old mother died in an auto accident this week, but he has no way of getting home until late January at the earliest. He must grieve from more than 200 miles away — in orbit, aboard the international space station.

It's a heartbreaking situation no other American astronaut has experienced. And it's made all the more tragic by Tani's devotion to his mother, Rose, who raised him and his siblings alone in suburban Chicago after their father died when he was 4.

"He is obviously pretty sad," the astronaut's brother, Richard Tani, said in Thursday's Chicago Sun-Times. "He was pretty close to her. We are all close to her. She was loved by everyone."

Tani's wife and a flight surgeon on the ground broke the news in a video conference call with the 46-year-old astronaut. But phone calls and e-mails from space are as close as Tani can get to the loving embrace of his family.

Tani has been on the space station since late October and had been scheduled to return to Earth as early as Monday of this week aboard the space shuttle Atlantis, but fuel gauge problems delayed the Dec. 6 launch until January.

A Russian Soyuz spacecraft is docked at the space station but must be reserved in case the two Americans and one Russian aboard need to evacuate the outpost in an emergency.

Unique situation

Tani's mother was struck and killed by a train in Lombard, Ill., on Wednesday. Police said she was stopped behind a school bus at a railroad crossing and decided to drive around the vehicle and the lowered gate.

"It's a unique situation to be on orbit, without a ride home maybe, for a long time and something this tragic happens in your family," said the Rev. Rob Hatfield, a minister at the elderly woman's church.

NASA prepares for all sorts of contingencies, and bad news from home is one of them. All astronauts are asked whether they would want to know about family emergencies right away or whether that information should be held back if they are preparing for an intense task such as a spacewalk, said Dr. Sean Roden, Tani's flight surgeon.

Tani, like nearly all his colleagues, wanted to know immediately, Roden said. Many have said they wouldn't want their family to go through the grief alone, he added.

NASA offered to let Tani take some time off, but he decided to carry on with his normal duties, including checking on science experiments, and "he's doing remarkably well for the information he's been given," Roden said.

A phone call away

Family, friends and counselors were just a call away on a private Internet phone line astronauts are allowed to use throughout their mission, NASA said.

"Everyone's dedicated to making sure that Dan has everything he needs," NASA spokeswoman Nicole Cloutier said.

The Tani family has not announced when the funeral will be held. Once that happens, NASA said, it will help Daniel Tani participate in any way he can, perhaps by a video or telephone linkup.

Slideshow 12 photos

Month in Space: January 2014

Cloutier said NASA is not at all concerned that Tani's grief could hinder his work or put his two crewmates in jeopardy. The space agency chooses astronauts with the emotional stability to handle tragedy, especially on long missions.

Frances Brach, a neighbor of Rose Tani's for 42 years, said being away will be hard on Daniel, who over his mother's objections flew home from Houston earlier this year after she had a heart attack.

While no other U.S. astronaut has lost a close relative in space, several have had to be told about accidents or major illnesses involving their family, said Dr. Smith Johnston, another NASA flight surgeon.

Every astronaut is assigned a psychological support group that helps him or her prepare for the anxieties of spaceflight, including missing family events big and small, said astronaut Clayton Anderson, Tani's predecessor aboard the space station. He said he was asked who he would want to notify him if something bad happened on Earth, and he chose his wife.

"I can only imagine what he's going through and how difficult a time it is for him," said Anderson, whose own mother died a week ago.

Kept in the dark

One person who does understand is cosmonaut Georgy Grechko, who was less than a month into his 96-day voyage aboard the Soviet space station Salyut 6 in 1978 when his father died. The Soviets decided not to tell him until the day after he landed — more than two months later.

It was the secretive Soviet era, when personal lives were subordinate to the needs of the state.

"I must admit that this news would have put me out of working form. I would have been half in space and half on Earth, beside my father's grave," Grechko, now 76, told The Associated Press on Thursday. "So I guess I must acknowledge that while it seems inhumane, it was probably the right decision."

The Soviets even sent him letters from his father after his death, via supply ships.

He said he asked to speak to his father upon returning to Earth but was told repeatedly that it was impossible to get through. He was finally told the truth only after he announced he would go to the nearest post office and use the phone there.

On Russia's Mir space station, visiting NASA astronaut Norman Thagard saw the effects of grief in space up close in 1995 when the outpost's commander, Russian cosmonaut Vladimir Dezhurov, struggled with the unexpected news that his mother had died. Dezhurov had to withdraw from contact with his crewmates for several days — and Thagard's observations led to changes in the way NASA handled giving bad news to astronauts in space.

In this age of instant communication, it would be hard for NASA to keep bad news a secret nowadays even if the agency wanted to, said Asif Siddiqi, a Russian space history expert at Fordham University.

AP Science Writer Seth Borenstein contributed to this report from Washington. AP writers Carla K. Johnson contributed from Chicago and Steve Gutterman contributed from Moscow. This report also was supplemented by msnbc.com's Alan Boyle.