The government is lagging far behind in declassifying its secrets and the problem is getting worse as agencies create billions more electronic records containing classified information.

In a report released Wednesday, a joint presidential-congressional advisory group urged greater openness, a sore subject for a White House roundly criticized for secrecy.

The Public Interest Declassification Board said President Bush can take immediate steps to address the issue.

For example, it says, the White House should retain the president's daily brief prepared by the CIA so historians, researchers and the public can eventually learn what the intelligence community tells the nation's chief executive.

The president's daily briefs

Secrecy and the president's daily brief became a contentious issue in the work of the 9/11 Commission, with the White House aggressively resisting public disclosure of the secret documents, including one that focused on Osama bin-Laden's intention to attack targets inside the United States.

The Aug. 6, 2001, daily brief the administration reluctantly released during the 2004 presidential campaign was entitled, "Bin Laden Determined to Strike in the U.S."

The board's report says the president could immediately create a national declassification program under the U.S. archivist to increase efficiency. Under the program, all federal agencies would report declassification decisions on a single computerized system.

White House spokesman Tony Fratto said it would be premature to comment on any specific recommendation in the report, which has been sent to heads of relevant government departments for review and comment.

'Too little has been done'

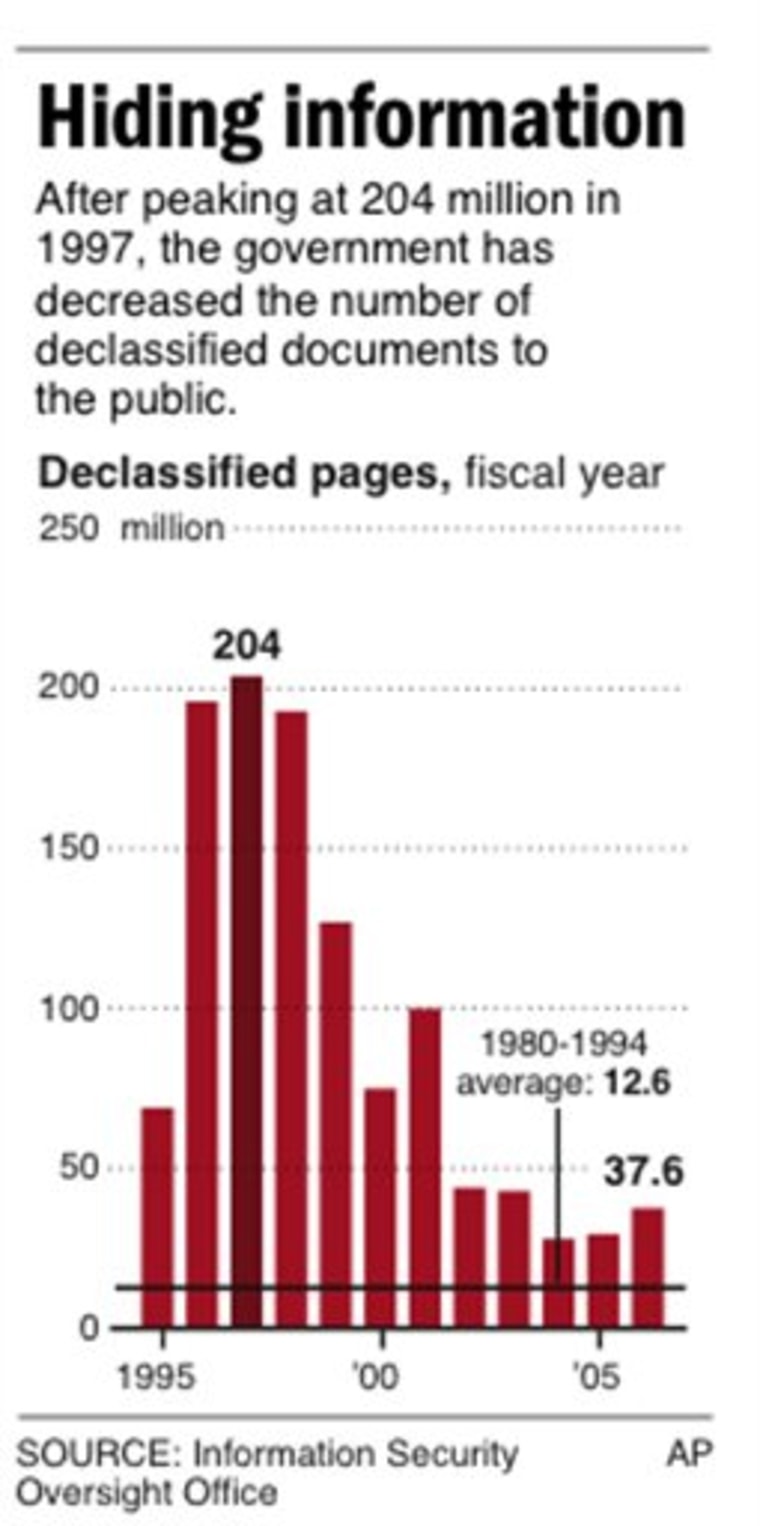

While more than a billion pages have been declassified since 1995, the report says the government has not yet come to grips with what it will face in the future.

"Too little has been done with regard to ... the truly monumental problem looming on the horizon: the review of classified information contained in electronic records," the report says.

In addition, it said, the government probably will be unable to meet a Dec. 31, 2011, deadline for reviewing classified information on microfilm, microfiche, motion pictures and sound recordings.

In 1995, President Clinton signed an executive order declaring that records would be presumed declassified when they reached 25 years of age.

At the time, it was believed this would encourage agencies to declassify records in bulk. Instead, agencies hired more personnel to review records, a process that took 12 years.

Presidential wake-up call

Meredith Fuchs, general counsel to the National Security Archive, a private group that seeks declassification of government secrets, describes the report as "a wake-up call to President Bush."

"The report paints a picture of a classification system bogged down by agency territoriality and reflexive secrecy," Fuchs said. "If this president won't deal with it, maybe the next one will."

The report shows that "as problematic as the current system may be, it's definitely ill-equipped to handle the challenges of tomorrow" with electronic records, said J. William Leonard, former director of the Information Security Oversight Office at the National Archives. Now retired, Leonard locked horns with the staff of Vice President Dick Cheney over the extent to which the executive order governing classified information applies to the vice president's office.

Among the recommendations:

- The president should create a system to identify historically significant classified records so they get priority in reviews for possible public disclosure.

- The U.S. archivist should establish a single center in Washington, D.C., to house all future classified presidential records from the end of an administration until their eventual declassification, when they would be transferred to the appropriate presidential library and made available to the public.

- The president should require a newly created National Declassification Center to create uniform guidelines to govern declassification across the government.

Created in 2000, the advisory board didn't receive federal money until late 2005. Five members of the panel are appointed by the president and four by Congress.