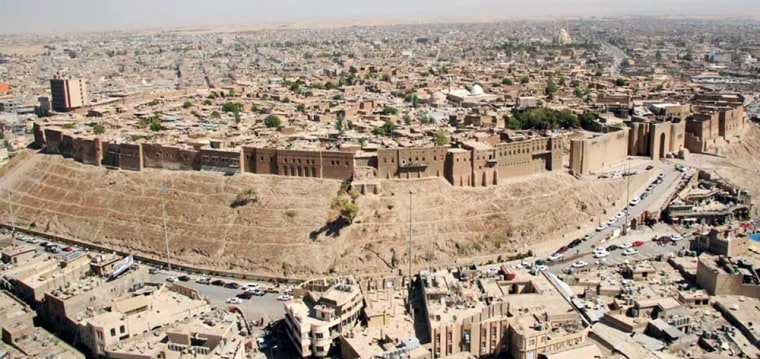

Towering above the modern streets and buildings of Irbil, the citadel's narrow alleyways and dusty courtyards stand almost deserted. Its mud-brick houses, built atop layers of ancient civilizations stretching back through millennia, are crumbling.

Irbil's citadel, claimed to be one of the longest continuously inhabited urban areas on Earth with a history of more than 8,000 years, is in danger. Its slopes are eroding and its buildings are collapsing.

But authorities in northern Iraq's autonomous Kurdish region have a plan to rescue it. They hope to turn the citadel, and the vast archaeological wealth buried within the mound on which it stands, into a world-renowned tourist site complete with hotels, coffee houses, art galleries — and a vibrant, permanent living community.

The planned reconstruction is a beacon of hope for Iraq's rich cultural heritage, and highlights the vast differences between the relatively tranquil Kurdish region in the north, and the violence in other parts of the country.

In Irbil, the Kurdish region's capital 350 kilometers (215 miles) north of Baghdad, the only indication that this is still a country at war is the tall concrete blast walls, featuring bucolic murals, that protect government buildings and major hotels from bombs.

Still, saving the citadel is a tall order. Of its more than 800 homes, "no more than 20 are in an acceptable state," said Mohamed Djelid, Director and UNESCO Representative for Iraq.

"You have now a very important monument ... in the heart of the city and it is dead," said Shireen Sherzad, who heads newly formed committee leading restoration efforts and is also an adviser to the Kurdish region's prime minister, Nechirvan Barzani.

Also, Sherzad estimates it will cost $35 million for the initial three years of the project, and for now, "We don't have any funding resources."

But all agree that the citadel, with its three mosques, its 650-year-old hammam, or Turkish bath, and homes with painted interiors and elegant arches, needs urgent attention.

The situation "is very critical. All the houses are crooked" and liable to collapse when it rains, says Ihsan al-Totinjy, the representative of a Czech company helping in restoration efforts and using digital imagery to map out the site.

The company, Gema Art Group, has taken more than 200 photos inside the citadel and another 250 outside, along with satellite images and 90 photos from a military helicopter, it said in a 2007 report. Before this mapping project, the most recent plan of the citadel was a map from the 1920s.

The company is also creating a virtual three-dimensional model, expected to be completed by the end of February, that will help pinpoint restoration needs.

Across Iraq, cultural and archaeological treasures are at risk — at best neglected, at worst looted, vandalized and bombed.

The International Council of Monuments and Sites, a Paris-based nongovernmental organization of experts, listed the citadel in its 2004-5 report on endangered sites in Iraq as one of five cases "where the damage was so serious that one can talk of cultural genocide."

Little is known about the early inhabitants of Irbil, but the citadel's secret is water — an abundant supply has maintained civilization after civilization.

The site "is a rich historical repository holding evidence of many millennia of habitation, more than 8,000 years old, making it the longest continuously inhabited site in the world," said UNESCO's Djelid.

The citadel sits atop a roughly 100-foot-tall mound formed by layers of successive settlements, including Assyrians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Persians and Greeks.

The epic Battle of Gaugamela, in which Alexander the Great defeated the Persian King Darius in 331 B.C., is believed to have been fought just 20 miles to the north, local authorities say.

The site has never been fully excavated. Recent geophysical tests have revealed what some believe could be an ancient temple buried beneath the center of the citadel, said Kanan Mufti, general director for archaeology of the regional government's Culture Ministry. Part of the project includes mapping areas for future archaeological excavation.

But there is much to be done before then.

Until little more than a year ago, the citadel was home to Irbil's poorest. Most earlier inhabitants left in the mid-20th century as they grew prosperous and built bigger homes on the plains below, said Mufti, who was born in the citadel and whose ancestors lived there for 500 years.

The squatters — including refugees who fled Saddam Hussein's onslaught against the Kurds in the 1980s — lived crammed into 25 acres between the fortified walls. With no sewage or drainage, the water seeped into the earth, eroding the slopes on which the citadel is built.

"Every day nearly 200,000 gallons of water were damaging the citadel," Mufti said.

Even the buildings themselves changed as inhabitants divided rooms and built extensions.

Without intervention, the citadel was doomed. So in November 2006, the 840 families living there were each offered a plot of land outside the city, with electricity, sewage and water, and $4,000 toward building a new home, said Irbil Governor Naouzet Hadi. All agreed.

The city also prevailed upon one family to accept compensation but stay in their citadel home to ensure there is no break in the site's continuous habitation, and to manage the pumps that control the water flow.

"I don't feel lonely — I like it here," said Hadida Hamademin Kader, who still lives with her seven children in a house near the center. The plan to renovate the citadel "has made us very happy," she said, pouring strong, sweet tea for visitors.

The committee's Sherzad acknowledges there's a long way to go, but says restoring the citadel is crucial.

"It is for all mankind," she said. "For Kurdistan, it's our pride."