Blind cavefish whose eyes have withered away may not be so blind after all.

Instead, a light-sensitive organ in their brains can detect light, research now reveals.

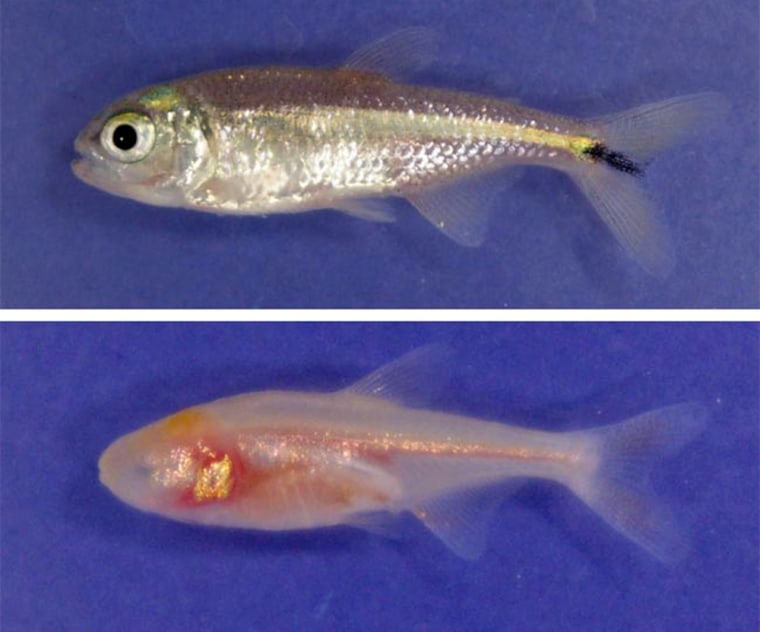

The blind cave-dwelling form of the Mexican tetra (Astyanax mexicanus) evolved from surface-dwelling ancestors whose eyes degenerated after the fish shifted their habitat into complete darkness a million or more years ago. These albino cavefish dwell today in freshwater caves in northeastern Mexico, with skin growing over their now useless eyes.

The discovery that cavefish could nevertheless sense light happened by pure luck, said researcher Masato Yoshizawa, a neuroethologist at the University of Maryland. As he was cleaning out bowls with young cavefish larvae in them, Yoshizawa saw that after a shadow passed slowly over their heads, the fish clearly responded by swimming to the surface.

Investigating the seemingly impossible, Yoshizawa and University of Maryland colleague William Jeffery checked the fish's eyes. Although adult cavefish lack functioning eyes, cavefish embryos begin developing eye structures early in their development, which later degenerate.

The researchers searched young cavefish for light-sensitive pigments, but did not see the molecules in the fish's eyes. However, Yoshizawa and Jeffery did find the compounds in the animals' pineal gland, an organ in their brains.

The pineal gland is present in most creatures with a backbone, including humans. The organ helps control the body's day-night cycle — hence its light sensitivity in fish. The pineal gland is also sensitive to light in amphibians and reptiles, but not in mammals.

When the scientists experimentally removed eyes and pineal glands from the young cavefish, they found the fish only retained their shadow response if they had their pineal gland too. In other words, the pineal gland helped them detect light.

So why might cavefish have preserved a way to see light after living a million or so years in the dark? One possibility is that caves are not always dark — for instance, cavefish might experience light near cave entrances or after cave-ins open windows in ceilings, the researchers said.

Another idea has to do with the fact that the pineal gland supplies the body with melatonin, a key hormone behind reproduction and growth. Although mutations could knock out the eyes of the cave-dwelling fish without causing too much trouble, withering away the pineal gland would lead to too many problems, Yoshizawa noted. As a result, the gland stayed, as did the light sensitivity it conferred.

The shadow response might have originally evolved to protect young surface fish, the researchers suggested. "When the larvae sense shadows of floating objects such as leaves, they hide beneath the object as a shelter, perhaps to avoid predators," Yoshizawa told LiveScience.

This light sensitivity fades away as the cavefish grow older, the researchers found. The light-sensitive molecules seem programmed to shut off, possibly after the eyes are supposed to kick in or when the skull gets too thick for much light to penetrate it.

Yoshizawa and Jeffery detail their findings Jan. 18 in the Journal of Experimental Biology.