The inspiration for CrimeReports.com came a decade ago when Greg Whisenant made the mistake of letting a stranger, who turned out to be a burglar, into his apartment building in Arlington, Va.

At a neighborhood meeting that soon followed, Whisenant was surprised to hear a woman say she had been followed in a parking lot. Whisenant pondered how technology could make a difference.

"Why can't we have some kind of alert system that would tell me something like that?" he wondered.

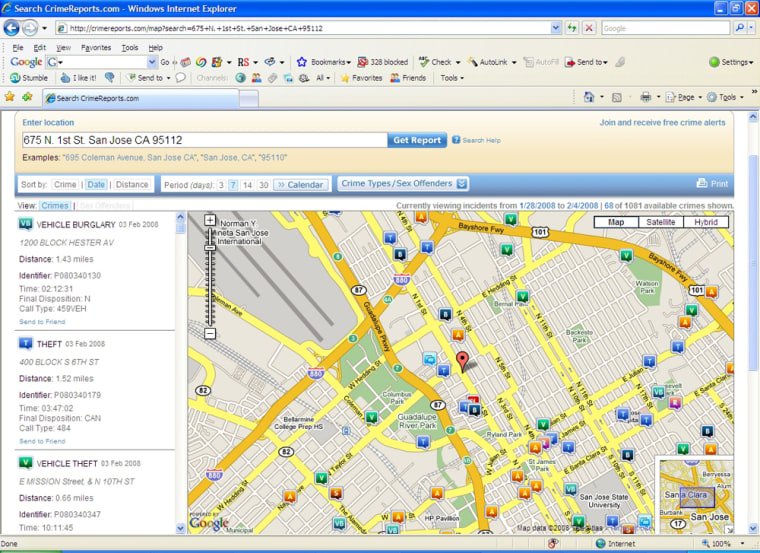

Now he has created it. A new service on CrimeReports.com, launched last year and expanding nationwide, overlays police reports on maps, so people can view where arrests and other police calls have been made. Users can configure e-mail alerts to notify them of crimes in locations of interest within a day.

The free site relies mainly on police departments paying $100 or $200 a month, depending on their size, to have CrimeReports.com extract the information from their internal systems and publish it online. Public Engines LLC, Whisenant's seven-person company in Salt Lake City, pledges to post no ads on the site.

About 40 law enforcement agencies have signed up, including police in San Jose, Calif., and several Utah jurisdictions. The site also captures and posts information from departments such as the one in Chicago that do not pay Public Engines because they had built their own links into their records.

This coincides with a prominent trend in policing. Since New York City police launched their "CompStat" system in 1994, law enforcement agencies around the country have been capturing and analyzing crime information in more careful detail, in hopes of better planning responses.

But these internal records generally do not come in a uniform, Web-friendly fashion. Even Web sites with crime maps, like the one operated by police in Washington, D.C., don't reveal details on individual reports. Instead such details often are made available in police logs sent to local newspapers.

What's new in CrimeReports.com is its system for extracting the files from disparate police databases.

Then it maps them online in one central location, through an easy Web trick known as a "mashup." Since Google Inc. opened its mapping software to third-party applications, free mashups like this have sprung up to let people plot everything from photograph locations to the sources of campaign donations.

One participant in CrimeReports.com, Sheriff Jim Winder of Salt Lake County, said the $200 monthly fee will be worthwhile mainly because the site provides a new way to increase his agency's public transparency.

"For people to have faith in and continue to be supportive of law enforcement, they need to feel we're divulging all we possibly can," he said. He added that the site's ability to make use of his department's "byzantine" records system was "almost revolutionary."

Officer Melanie Hadley, a spokeswoman for police in Montgomery County, Md., said that before working with CrimeReports.com, her agency could offer no search engine to let people "pinpoint exactly what was going on" in certain areas.

This flood of information could have its downsides.

CrimeReports.com lists only the block on which a crime occurred or was reported, not the actual address, so as to protect victims' privacy. Even so, the Salt Lake sheriff noted that neighbors on a tiny street might be able to figure out, say, which house on their block had a domestic incident that the participants would rather keep quiet.

While that kind of information was always available in department records, "`public' and `readily accessible' are two different things," Winder said.

CrimeReports.com's likely users might be prospective home buyers or neighborhood watch groups seeking insights into criminal activity. Yet it's unclear whether seeing all the police reports from a certain neighborhood will provoke more paranoia than caution.

"It's not our job to censor or to limit or preclude the information we give out," Winder said. But he added: "It is a double-edged sword. More data doesn't always equate knowledge."

Whisenant acknowledges that the site needs to improve its user friendliness. For example, clicking icons for police reports in San Jose brings up such arcane notations as "Final Disposition: A" and "Call Type: 242."

Eventually, Whisenant hopes to integrate more narratives from police reports. CrimeReports.com's partners in Washington, D.C., police already include that for some reports, in classic "Dragnet" tone: "S-1 then struck C-1 in the face with his fist causing C-1 to fall to the ground."

Whisenant believes that with an easier view of such information, people might respond by taking a little bit more care — leaving a porch light on or closing the garage door, for example. What else people do with the data, he suggests, is anyone's guess.