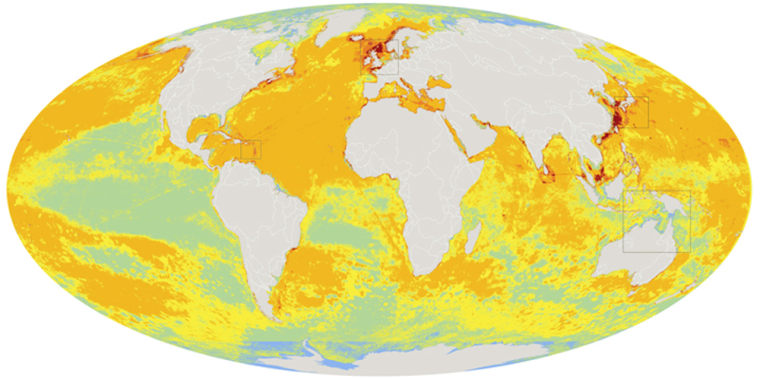

The first-ever comprehensive map of our planet's marine environment shows that human activity has heavily affected 41 percent of the world's ocean-covered area, with no area left completely untouched.

The atlas, which was unveiled here Thursday at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, was drawn up by combining impact data for 17 different activities, ranging from fishing and commercial shipping to pollution and climate change.

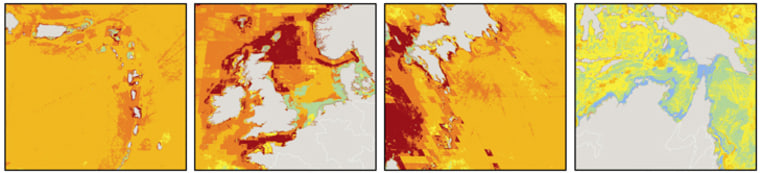

Coral reefs, continental shelves and the deep ocean were the hardest-hit ecosystems, the international team behind the research reported. The biggest human impact was seen in the North Sea, the South and East China Seas, the Caribbean and North America's East Coast. The least-affected areas were largely near the poles.

Although such impacts have been studied individually before, the team members said their atlas, based on four years of research and published in Friday's issue of the journal Science, represented the first attempt to synthesize all those studies into one global database.

"For the first time, we have produced a global map of all of these different activities, laid on top of each other, so that we can get the big picture of all the impacts humans are having," Ben Halpern, the study's lead author, told journalists Thursday.

That big picture looks considerably worse than previously thought, said Halpern, who is an assistant research scientist at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, or NCEAS, based at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

The extent of ocean degradation was underlined by yet another study appearing in Science: Oregon State University zoologist Jane Lubchenko and her colleagues reported that an oxygen-poor "dead zone" off central Oregon's coast was spreading into the California Current ecosystem.

Updating previous studies of the dead zone, the researchers said oxygen levels had fallen to virtually nil, and they reported the "complete absence" of fish from rocky reefs. They said the zone's degradation seemed to be accelerating.

Halpern and his colleagues said their database could be used to track further degradation — or improvement — in the global ocean environment over the years to come. NCEAS is making the maps of human impacts available via an interactive Web site.

How the maps were doneThe maps are based on a computer model that assigned scores to the 17 human activities, based on their current predicted impact on the world's oceans. The 17 categories included six methods of fishing, five types of pollution, three measures of climate change (ocean acidification, ultraviolet exposure and sea temperature) and the effects of alien species invasion, commercial shipping and sea-bottom structures.

John Bruno, a researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was involved in the effort to draw up a database of climate change effects over the past 20 years based on satellite measurements.

"This new picture of ocean warming reveals a far greater degree of local ... variation in temperature anomalies than previously recognized or even anticipated," Bruno said in an e-mail to msnbc.com.

The model accounted for the fact that the effects of the 17 activities varied by ecosystem. For example, previous research has shown that fertilizer runoff has a large effect on coral reefs but a much smaller one on kelp forests.

To gauge that varying effect, scientists broke the ocean into millions of square-kilometer cells. Then they calculated the combined impact for each cell, based on the formulas in the computer model. That produced a "human impact score" for every square kilometer of the ocean.

Finally, they checked the predicted impact against previous studies to make sure their model was a close match for the actual data.

Halpren said the areas where humans were judged to have medium high, high or very high impact added up to 41 percent of the total. "Once you get to 'medium high impact,' the oceans are degraded to a level that most people would not be happy with," Halpren explained. Some species might be missing from the top of the ocean food chain, and there would be warning signs for coral reefs and other habitats.

"Things might look OK, but they're far from what they used to be or could be," he told msnbc.com.

In their research paper, the scientists noted that their assessment depended on "expert judgment," and that the method resulted in "a different picture of ocean condition compared with simply mapping the footprints of human activities or drivers."

They acknowledged that the computer model was incomplete: On one hand, the apparent impact on coastal areas could have been inflated because of the way separate impacts were added up. On the other hand, the model didn't account for impacts ranging from unreported fishing to atmospheric pollution.

Fio Micheli, a member of the research team from Stanford University, said the model would be refined and updated as more readings become available. The fact that so many human activities are still unaccounted for "actually makes our analysis conservative," she told reporters.

The scientists voiced particular concern about the seas of the Arctic and the Antarctic, which are currently the least-affected areas of the world's oceans.

"Unfortunately, as polar ice sheets disappear with warming global climate and human activities spread into these areas, there is a great risk of rapid degradation of these relatively pristine ecosystems," Carrie Kappel, a scientist at NCEAS, said in a news release.

NCEAS' Halpern said the news wasn't all bad.

"Small patches of these low-impact areas exist around the planet," he said. "Almost every country has some of these in their backyard, providing real opportunities for effective management and conservation in these areas."

The scientists said policymakers could use their atlas to coordinate preservation efforts — for example, by rerouting shipping lanes to reduce the impact on areas already hard-hit by overfishing. "Our approach may be used to identify regions where better management of human activities could achieve a higher return on investment," the researchers wrote.

In Thursday's news release, Halpern said the study should serve as "a wake-up call ... rather than a reason to give up."

"Humans will always use the oceans for recreation, extraction of resources, and for commercial activity such as shipping," he said. "Our goal, and really our necessity, is to do this in a sustainable way so that our oceans remain in a healthy state and continue to provide us the resources we need and want."

The research was funded by NCEAS, with support from the National Science Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. In addition to Halpern, Bruno, Micheli and Kappel, the authors of the Science paper include Shaun Walbridge, Colin Ebert and Matthew Perry of NCEAS; Kimberly Selkoe of the University of Hawaii; Caterina D'Agrosa of the Wildlife Conservation Society; Kenneth Casey of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Helen Fox of the World Wildlife Fund; Rod Fujita of Environmental Defense; Dennis Heinemann of the Ocean Conservancy; Hunter Lenihan and Elizabeth Madin of UC-Santa Barbara; Elizabeth Selig of UNC-Chapel Hill; Mark Spalding of the Nature Conservancy; Robert Steneck of the University of Maine; and Reg Watson of the University of British Columbia.